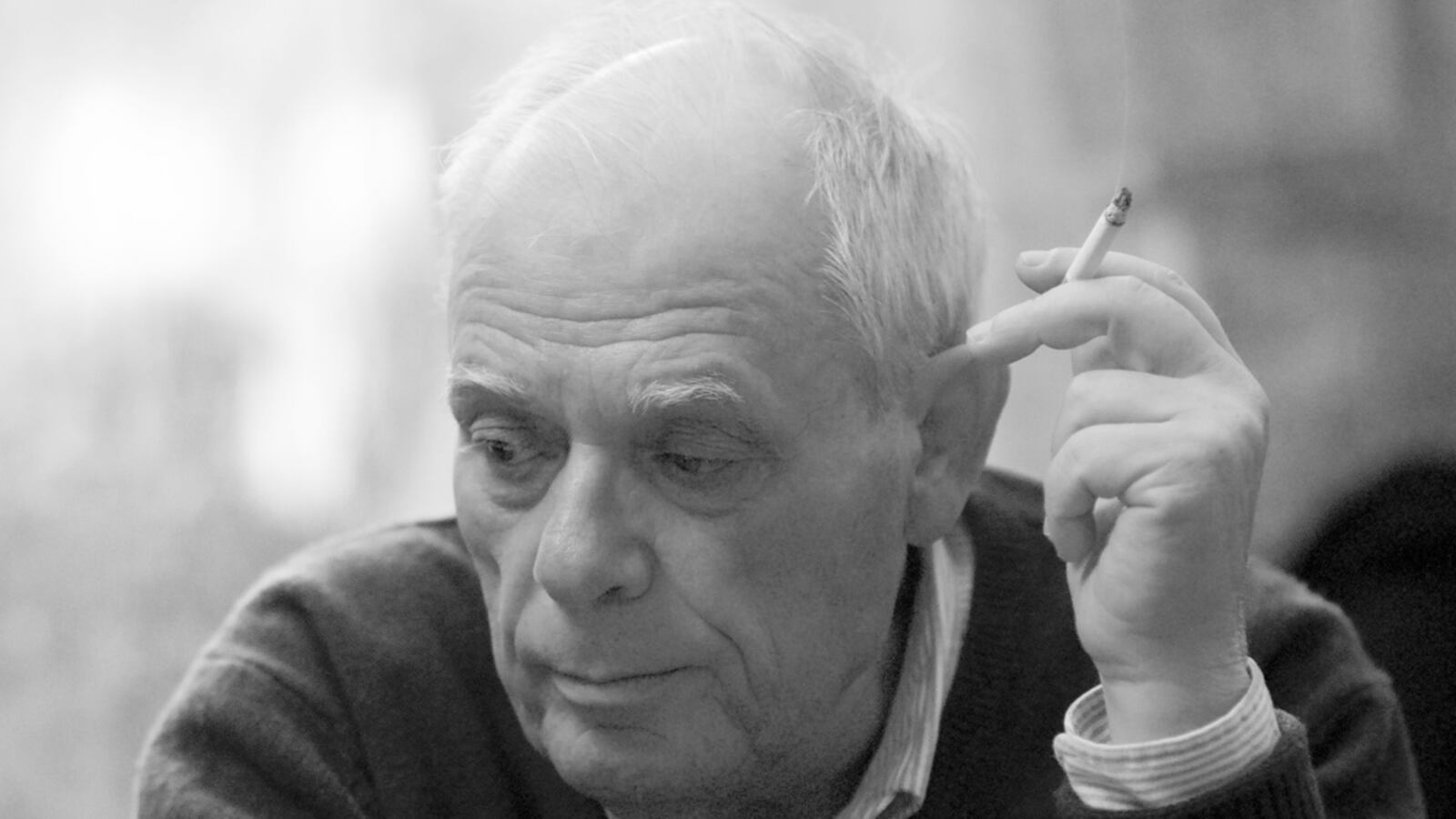

The Portuguese novelist António Lobo Antunes is the most important living writer you've probably never heard of. A household name in Portugal, a celebrity across the Latin world and an icon in France, he has nevertheless remained partially obscured in the international shadow of his near-contemporary, the late José Saramago, who won the Nobel Prize in 1998. Saramago's death last year might have promoted Lobo Antunes to Portgual's greatest storyteller but he has been all along Saramago's better as the insistent siren of Portuguese history, the dark crooner of a nation's conscience. Lauded by the best minds in literature—Harold Bloom, George Steiner, and J.M. Coetzee among them—Lobo Antunes crafts macabre fever dreams as if possessed by an abler Poe, and few other novelists have his Bellovian ability to see both deeply and minutely, to render the world, the fallen world, as if never rendered before.

Still, many American readers remain contentedly averse to serious novels in translation (Stieg Larrson is not serious), as if they were the gypsies of fiction: could be a danger, could be a revelation, might be arduous to understand, so best just to leave them alone. Many readers are averse also to universal truths too dour for easeful consumption, and Lobo Antunes' truth-telling is about as dour as it gets. Where Saramago often brought playful allegory, half-grinning subversion, and the reluctant optimism of an idealist (his leftism always endeared him to international audiences), Lobo Antunes brings an almost taunting fearlessness in the face of existential squalor. Europeans are generally more accepting of a novelist's nightmarish vision; in America we like our visions with a little sunlight, or, to echo William Dean Howells: Americans don't mind a tragedy as long as it has a happy ending. But the time has come to welcome to our shores this world-class weaver of seductive sentences whose horror-tinged genius is necessary for a fuller understanding of our lives. We are not whole without him.

Margaret Jull Costa—Saramago's translator who is poised to become heir to the great Edith Grossman—has just released her definitive translation of Lobo Antunes' second novel, the antiwar dirge The Land at the End of the World. (The first English translation, titled South of Nowhere, appeared in 1983 incomplete and badly marred to boot.) Published in 1979, six years after Lobo Antunes returned from Portugal's asinine colonial war in Angola, The Land at the End of the World established him as a preeminent European novelist unafraid of spotlighting the hell inside us. Lobo Antunes worked for two years as a psychiatrist and medic during that war, elbows-deep in demons and blood, cursing the warped politicians in Lisbon who had sent him and his countrymen to be butchered in “the asshole of the world.” As Jull Costa suggests in her artful introduction, the pointless slaughter of that campaign scorched him to his core and supplied all the darkness for his earliest books.

The Land at the End of the World unfurls over the course of a single evening as the unnamed, alcoholic narrator addresses a silent woman in a bar, telling of the carnage he witnessed as a doctor in Angola. His disenchantment, sense of absurdity, and separation from God are as consummate as Geoffrey Firmin's, the alcoholic consul from another masterwork of cavernous, bat-filled psychology, Malcolm Lowry's Under the Volcano. From the bar to the bedroom, the narrator's sex/death seduction song is also to his survival hymn: In the nightly retelling of atrocity and despair, he achieves communion, and punctures, however briefly, "the hopeless opacity" of his existence. "Look at me and listen," he says, "I so need you to listen." His is a storytelling of sustenance, the One Thousand and One Nights of a former Portuguese army medic who tries to stay his own self-inflicted execution through confession and coitus. How else to beat back nihilism in a world turned absurd, abandoned by the holy? He tells his listener: "I'm searching for an empty space in which I might drop anchor... the long mountain range of your body, some recess or hollow in your body where I can lay my shamefaced hope." Like Nick Adams, Hemingway's shell-shocked hero who can't sleep in the dark for fear of losing his soul, Lobo Antunes' narrator can't sleep alone for fear of disappearing altogether.

For a novelist who shares Rilke's death obsession and ancient, dark interiority—the body count is high across his nine novels translated into English—Lobo Antunes makes serpentine sentences that buzz with vibrancy and immediacy, page-long sentences with the improvisational quality of jazz that turn far within themselves before bursting with light and life (a jazz fan, the narrator speaks of Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and Ben Webster as if they were the last path to delight). And that zooming eye never falters: Morning brings "the polar, crepuscular unreality than enfolds objects and faces in the same kind of transparent halo that perches on the tops of pine trees"; masturbating soldiers "were pistons huddled in our icy sheets like aged fetuses no uterus would ever expel"; visiting officers from Luanda looked "preserved in the formaldehyde of air-conditioning"; "cobras lay coiled in soft dungy spirals, and the crocodiles seemed reconciled to their Tertiary Age fate as mere lizards on death row."

If animals are Lobo Antunes' preferred metaphor—the novel begins at the Lisbon zoo—it is because he apprehends the world with the sensibilities of both Dostoevsky and Darwin, refusing to ignore the beasts we are, the monstrous afflictions we foist upon ourselves and others. The narrator wishes to make love "as furiously as rhinoceroses with toothaches... two pachyderms intent on devouring each other amid a concert of squeals." Again and again soldiers are referred to as animals, as cretins turned lunatic by such "senseless, imbecilic violence." As a boy, he could hear his parents in bed, "making a noise like the toothless, lumbago-ridden elephant clanging its bell" (the young Kafka, too, was outraged when overhearing his parents make love in the night).

Lobo Antunes might be as flesh-infatuated as any true Catholic, current or lapsed, but his fixation on the animality of our bodies is both a doctor's practical engagement—Maugham had it—and a source of spiritual succor. The Land at the End of the World culminates not in a trendy dejection but in the possibility that we can still provide sanctuary for one another, that storytelling can save lives, that a lyrical consciousness is capable of lasting beauty. This Portuguese genius has seen too much, indeed, but in giving witness to the wasteland he has given us wonderful gifts.