In mid-October 1986, Yitzhak Shamir was about to begin his second term as Israel's prime minister. In anticipation, a top settlement planner from his Herut party prepared a map hand-marked with sites for new settlements in the West Bank. I'd seen the map, because the planner accidently handed it to me during an interview, then had an aide call me to ask desperately for it. His boss needed it for a meeting with Shamir.

Shamir was returning to the premiership under a power-sharing agreement with Shimon Peres's Labor Party. Shamir didn't adopt the settlement proposal, which would have required a loud fight with Labor. He didn't need to, because Labor acquiesced as a government-financed housing boom continued in existing settlements. From 1983, when Shamir succeeded Menachem Begin and began his first stint as premier, until 1992, when he lost to Yitzhak Rabin, the number of settlers in the West Bank and Gaza quadrupled. (That's based on government figures, which don't include East Jerusalem.) During the 1992 campaign—despite U.S. pressure to stop building—his government launched bus tours to suburban settlements where homes were on sale for a bit more than nothing.

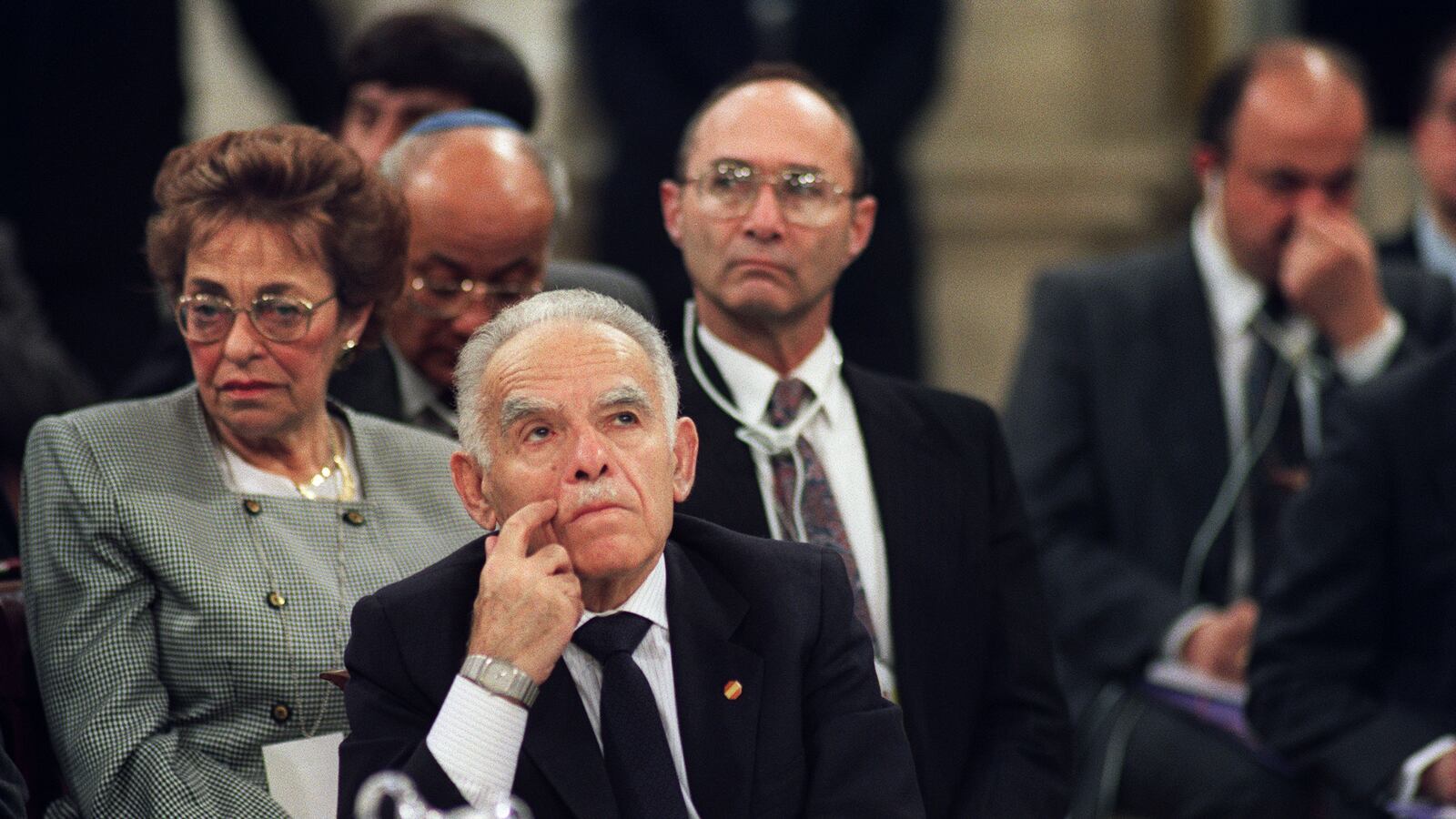

Shamir, who died Saturday at 96, was a very quiet, utterly relentless man, devious but incorruptible, rigid as rock. Since the custom is to praise the dead, critics and adversaries have looked back wistfully at his lack of ego. His successors have made him look better. He would not have smoked Ehud Olmert or Benjamin Netanyahu's overpriced cigars, or lived in Olmert or Ehud Barak's ostentatious homes. If he was capable of Netanyahu or Ariel Sharon's bombast, he hid the ability with many other secrets. Then again, he could never have reinvented himself as Olmert, Peres and Yitzhak Rabin did, embracing new ideas about peace. Despite his modesty, let us not be nostalgic for Shamir: He began and ended his career as an extremist who damaged the cause of Jewish independence to which he was dedicated.

As a young man in pre-state Palestine, Shamir moved from the rightwing Irgun underground to the breakaway Lehi, the faction so single-minded about driving the British from Palestine that it would not suspend its violence while Britain fought the Nazis. Lehi promoted grandiose fantasies of a "third kingdom" of Israel and—according to scholar David Rapoport—was the last twentieth-century organization to identify proudly as a terror group. After founder Avraham Stern was killed, Shamir became part of Lehi's ruling triumvirate. In that role he authorized the 1944 assassination of Lord Moyne, the British Minister Resident in Egypt, and the assassination of Count Bernadotte, the U.N. negotiator who sought to end the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. "Haunted by conspiracy theories," as another scholar wrote, Lehi was sure that Bernodotte was plotting to bring back the British.

Post-independence, Shamir found a place back in the shadows as a Mossad agent. Eventually he joined Herut and entered politics. In 1978, as Knesset Speaker, he abstained in the vote on the Camp David Accords with Egypt. Menachem Begin, leader of his own party, had negotiated the agreement, but Shamir could not vote for peace at the price of land.

By Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon, he was Begin's foreign minister. On September 17, the morning after the Christian Phalange militias entered the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps, Communications Minister Mordechai Zipori phoned Shamir. Zipori later testified to the Kahan Commission of Inquiry that he'd been told by a reporter that the Phalangists were massacring civilians, and that he told Shamir so. Shamir would testify that he'd heard something more vague, and besides he knew Zipori as a critic of the war. He did nothing about the call, and the slaughter continued. What Shamir really heard remains another of his mysteries. But in the best case, his view of Zipori as an ideological moderate was enough reason not to inquire further.

As prime minister, Shamir presided over political stalemate at home, diplomatic stagnation abroad, and entrenchment in occupied territory. In 1987, he blocked cabinet approval of the London Agreement, negotiated between Peres as foreign minister and Jordan's King Hussein. The agreement would have led to peace talks between Israel and a Jordanian-Palestinian delegation–and to giving up part of the Whole Land of Israel. Shamir believed the occupation could last forever. The Intifada that broke out that year did not change his mind. His mind was not changeable.

After he lost office, the old revolutionary faded into the oblivion of old age. To his successors on the right, he did not succeed in bequeathing his modesty or calm. To Benjamin Netanyahu, he did bequeath his belief that it was possible to negotiate forever to avoid reaching an agreement; that the status quo of occupation could continue. The good that Yitzhak Shamir did will be interred with him; the evil, it seems, lives on.