Clearly, the President’s bold attempt to woo Iranian moderates backfired.

Despite his taking great political and diplomatic risks to move Iran’s mullahocracy beyond its aggressively anti-American stance, Iranian hooligans still shouted “Death to America” in Tehran’s streets while “The Supreme Leader” condemned America from his perch. Nevertheless, the President and his equally deluded aides invested so much in this moderate breakthrough, he was willing to risk offending Congress, trying to bypass its constitutionally—sanctioned foreign policy input.

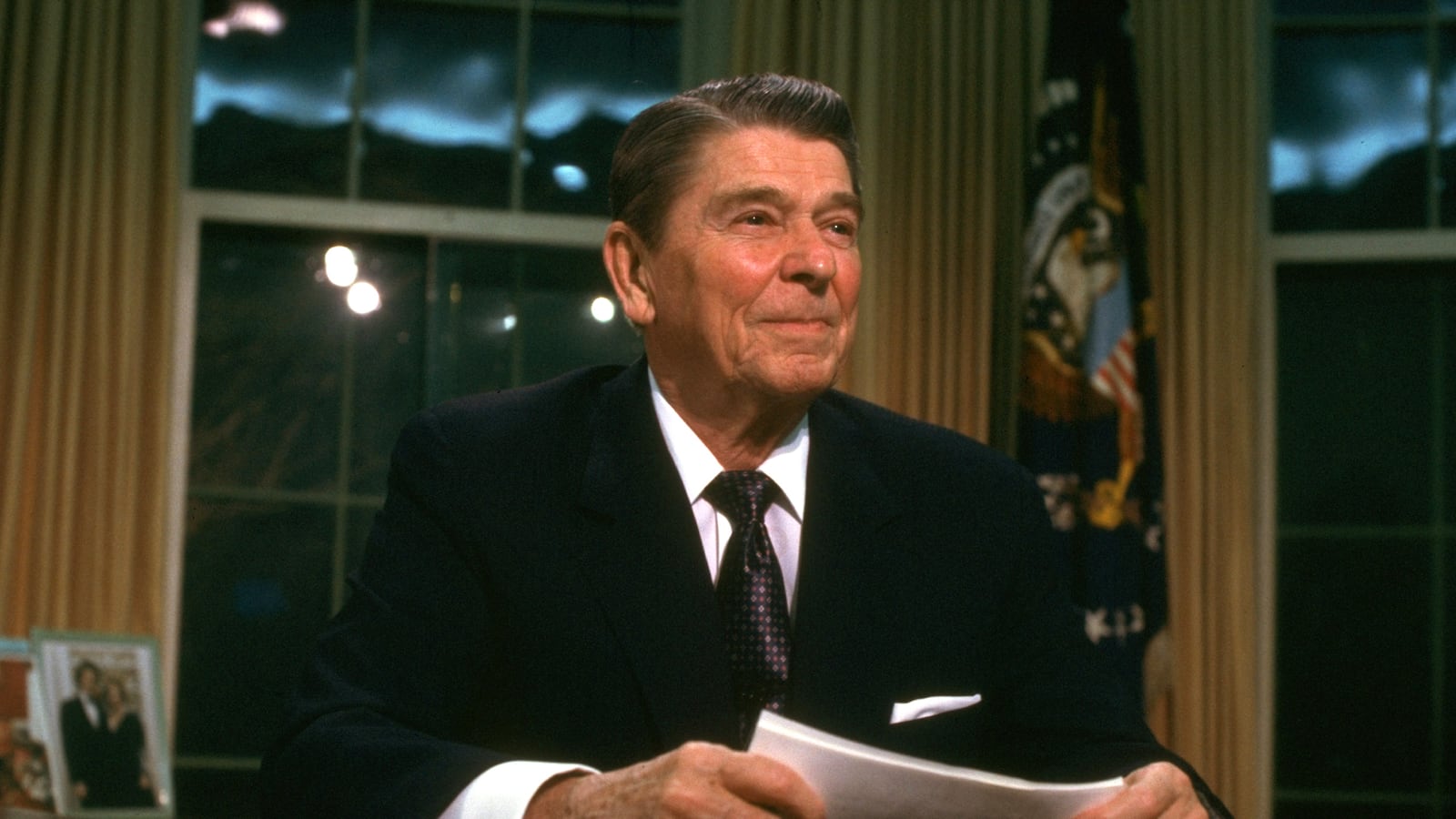

No, this is not some neocon attack on President Barack Obama’s recent sanctions-lifting nuclear agreement with Iran. This description of the Iran-Contra affair harks backs to July 1985 when the Republican Ronald Reagan tried freeing American hostages and boosting Iran’s supposed moderates by resupplying Iran with American weapons and spare parts. Wherever you stand on today’s Iranian nuclear deal, it is worth analyzing the Iran contra-dictions, asking what, if anything, has changed.

Thirty years ago, while recuperating in the hospital from colon cancer surgery, Ronald Reagan learned about a zany attempt to free seven American hostages Hezbollah terrorists held. The scheme proposed using Israeli intermediaries to sell arms to Iranian moderates, who promised to improve relations with America once the fiery octogenarian Ayatollah Khomeini died. Desperate to free the hostages and hoping that wooing Iran would confound his main cold War-era enemy, the Soviet Union, Reagan approved.

On July 17, four days after his intestinal procedure, and 17 days after his most recent public statement vowing “no deals” with terrorists, Reagan wrote in his diary: “Some strange soundings are coming from some Iranians.” These “soundings” led to the first Israeli arms shipments to Iran in August and the release of one hostage by September. This indirect exchange amounted to what the final Iran-Contra report would call “an authorized effort to secure the release of American hostages in exchange for shipments of weapons.” Eventually, Iran received 2,008 TOW anti-tank missiles and tons of spare parts. In return, three hostages were freed, although Iranian-supported Hezbollah terrorists kidnapped replacements shortly thereafter.

Reagan’s aides tried keeping this initiative secret. In 1980, mocking Jimmy Carter’s wimpiness when Iran held 52 American diplomats and Marines hostage for 444 days, Reagan had vowed never to negotiate with terrorists. Reagan’s cowboys also feared being embarrassed by the crafty, hostile, Iranians whose taqiyya doctrine, or “holy dissimulation,” celebrated tricking the West and whose dictatorship thrived by bashing “Big Satan,” meaning the United States, not just “Little Satan,” meaning Israel.

An even kookier, riskier scheme intensified this need for subterfuge. Frustrated by congressional bans on funding the Contra insurgency against Nicaragua’s Sandinista government, Colonel Oliver North and others diverted Iranian arms sale profits to bankroll the Contras. Three times, in increasingly global language, the Democratic-dominated Congress had passed a “Boland Amendment” outlawing any Contra funding. Reagan resented the congressional restrictions on those he called “the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers.” What became the Iran-Contra scheme unconstitutionally subverted congressional oversight of the Administration’s foreign policy.

Inevitably, in fall 1986, a Lebanese newspaper leaked the story, derailing—and almost destroying—Reagan’s presidency. Forced to admit to either a cluelessness that bordered on incompetence or a lawlessness that could be impeachable, Reagan punted. Resenting the pesky congressional restrictions handcuffing him, bleeding politically left and right, Reagan languished for months. In March 1987, he apologized, sort of. In what would become a model of presidential double-speak, Reagan proclaimed: “A few months ago I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages. My heart and my best intentions still tell me that’s true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not.”

Ultimately, few Americans had the stomach for impeachment a decade after Watergate, while Reagan’s surprising love-in with Mikhail Gorbachev’s Soviet Union redeemed his presidency. But the Iran-Contra scandal continues to cloud Reagan’s reputation—and some of its lessons remain relevant.

Underlying the outreach to Iranian “moderates” was a traditional, delightfully innocent, American belief in the power of reason and reasonableness. George Washington is remembered for championing an Enlightenment-era neutrality rooted in rationality in his Farewell Address, assuming that most people are good. He advised: “Just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated.”

Supporters of today’s Iran deal echo Washington’s warning that a nation with permanent enemies—or friends—“is in some degree a slave…. Antipathy in one nation against another disposes each more readily to offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and intractable, when accidental or trifling occasions of dispute occur.”

Skeptics, however, note that Jimmy Carter fell for the Iranians’ boombox revolution, overlooking the menacing Islamist fundamentalism in the seemingly benign cassette tapes the Ayatollah Khomeini’s supporters distributed opposing the Shah. Ronald Reagan and his aides fell for Iran’s Diet Coke moderates, who were not “The real thing.” And, whatever one thinks of the recent agreement, the level of anti-American rhetoric that Tehran is still spewing remains terrifying, especially with four hostages languishing.

Obama is banking on a Washingtonian reason to free Americans from considering the Islamic Republic of Iran an enemy; Obama’s critics fear Obama is joining a bipartisan parade of American innocents, who, enthralled by their own goodness, trust others to be equally benign.

Barack Obama’s risky outreach to moderate Iran comes 30 years after Ronald Reagan’s risky outreach to supposed Iranian “moderates.” Both diplomatic gambles reflect this longstanding American faith in reason and quest for reasonable centrists even amid our sworn enemies. Both express an idealistic faith in diplomacy overriding an equally idealistic faith in defending individuals’ human rights while checking the realists’ pessimism. And both involve presidents trying to maximize their foreign policy prerogatives, dismissing—and in Reagan’s case illegally violating—congressional oversight. Reagan’s initiative quickly degenerated into the Iran-Contra catastrophe. The fate of Obama’s new agreement probably won’t be clear for a while, yet the menace of Iran’s Islamist tyranny clearly persists.