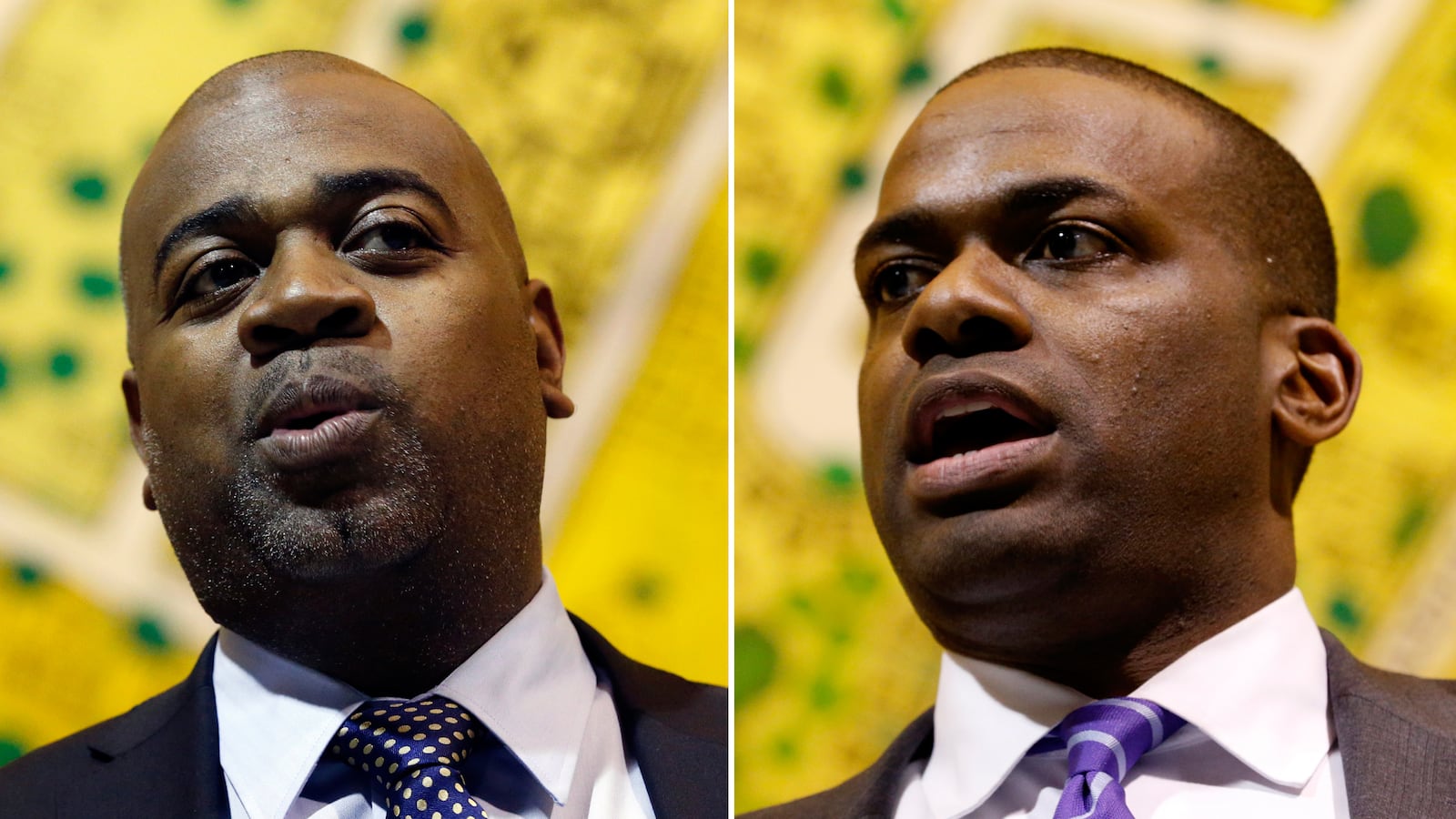

Voters in Newark, the largest city in New Jersey, will vote for a new mayor next Tuesday to replace Cory Booker, who rode a wave of national attention into the Senate last fall. The election comes at a moment when Newark, long one of America’s most dangerous and depressed cities, is experiencing a nascent revival. The stakes are high and the candidates offer a stark choice: Ras Baraka, a radical councilman from Newark’s South Ward, is up against Shavar Jeffries, a former Assistant State Attorney General and reformer. Baraka has enjoyed a significant lead, but the race is tightening and an explosive video posted to a mysterious Web site this weekend could shake things up in the campaign’s final week.

Baraka is a firebrand whose politics of racial resentment would seem out of date many places in 21st-century America, but still resonates in Newark. The son of Amiri Baraka, the controversial poet and essayist who died in January, Baraka also dabbles in poetry and was featured on Lauryn Hill’s 1998 record The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. But unlike his father, who abhorred politics, Baraka has spent most of his life in the political realm.

After graduating from Howard University and obtaining a master's in education from Saint Peter’s in Jersey City, Baraka ran for mayor in 1994 when he just 24 years old and teaching in Newark’s public schools. During Sharpe James’ infamous 20-year tenure as mayor of Newark, Baraka served as deputy mayor and was later appointed to serve the term of a councilman who passed away. Baraka lost his council seat in the 2006 election that brought Cory Booker to City Hall. He then became principal of Newark’s Central High School and was elected to represent Newark’s South Ward on the city council in 2010. (Newark is divided into five political wards.) He remained on as principal of Central High until just a few months ago.

Shavar Jeffries’ life story is straight out of Horatio Alger. His father abandoned him. His mother was killed by an abusive boyfriend when he was 9. He was raised by his grandparents in Newark, did well in public school, and then received a scholarship to attend the prestigious Seton Hall Prep. From there he went on to Duke and Columbia Law School, clerked for the NAACP and a federal judge, and then began a career as a lawyer and a professor at Seton Hall Law School. From 2008 to 2010, he served as New Jersey’s Assistant Attorney General and helped to create a prisoner reentry program that produced a 26% reduction in recidivism of ex-offenders.

The race for mayor was ugly from the start—Baraka showed up at Jeffries’ home at 9:30 one night and the two men got in a shouting match; a low-level Jeffries campaign worker set fire to the Baraka campaign bus—but the heat was turned up this weekend when a Web site of unclear origin posted a 10-minute video of a Baraka diatribe. In it, Baraka indicates that whites are the “enemies” of blacks and suggests “We got to plan to remove them and then we got to seize power.” He was apparently addressing gang-affiliated teenagers and trying to impart a message of black empowerment, but even in context the language is extremely inflammatory.

The central issue of the campaign has been education, a subject both men know well. Baraka has been a teacher for 20 years and graduation rates and test scores have improved during his tenure as principal of Central High, albeit from a low starting point. Jeffries has been president of Newark’s School Authority Board and helped launch one of the city’s most successful charter schools.

Baraka’s candidacy has benefited from his opposition to School Superintendent Cami Anderson’s controversial One Newark school reorganization plan. What Anderson is trying to do is actually very progressive. All schools, traditional public schools and charters, would be put on a common application. Parents would list their top choices and the district match up students with schools. Cities like Denver and New Orleans have begun using this approach with great success. It makes it easier for students to enroll in charters and ensures that charters are serving their fair share of students with special needs.

But Anderson’s plan, which involves closing a handful of schools, has met with a firestorm of controversy. Even supporters admit the way Anderson has introduced the plan has been high-handed. Jeffries, who is in support of school reform in general, calls Newark One’s roll out “incompetent.” Newark schools were put under state control in the early 1990s, so Anderson is an appointee of the Christie administration and not under the control of Newark’s mayor. Still, the mayor of Newark can cause a lot of problems and Baraka insists Anderson must go if he is elected mayor. Also at stake is the innovative teachers’ contract that the district signed to national acclaim just 18 months ago.

More complicated is the issue of charter schools. About 25% of Newark students now attend charter schools. Stanford University’s education research team recently found that Newark charter schools have posted “some of the largest learning gains we have seen to date,” with Newark students’ gains roughly equivalent to spending an extra seven to nine months in school each year. Thousands of children are on wait lists to get in charters and Baraka insists that he supports them as part of the overall system. But he introduced legislation in the city council in 2013 to place a moratorium on the opening of any new charters and voted against nine of 10 charter school lease agreements.

Crime is another issue where the contrast is sharp. Jeffries touts his law enforcement background as assistant attorney general. Baraka has written letters in support of convicted gang lord Al-Tariq Gumbs. Baraka actually suggests that his ties to gang leaders would allow him to broker a peace among the gangs of Newark. But that theory doesn’t hold much water when you consider that crime is up 70% in his district since he became the councilman.

Whoever is elected on Tuesday will take over a city with a multitude of problems. Nearly half the kids in Newark drop out before graduating from high school. Crime, which decreased in the early years of Cory Booker’s mayoralty, went right back up after the city laid off 167 cops a few years ago due to budget cuts. Last year, 111 people were murdered in Newark, the most since 1990. The unemployment rate is 13%, nearly double the national average. The budget is a mess and officials in Trenton are whispering about a state takeover of the city's finances.

At the same time, however, Newark’s downtown is undergoing a mini renaissance. The city has invested heavily in new and refurbished parks, including a boardwalk along the Passaic River. Panasonic moved its North American headquarters to a new office building. Prudential is building a new 20-story tower. Audible.com, the world’s largest producer of audio content, now calls Newark home. A $150 million Richard Meier-designed Teachers Village project just opened. It includes three charter schools and 205 apartments for teachers. The historic Hahne department store building is being turned into a Whole Foods with 200 new apartments above. Several other downtown properties have been brought back to life as residential lofts. Rutgers is turning an abandoned 1920s skyscraper into dorms for 400 students. A Courtyard by Mariott, Newark’s first new hotel in 40 years, recently opened, and a new, swanky Hotel Indigo is set to open steps away.

Many in Newark’s business community remain nonplussed by the idea of a Baraka mayoralty. They note that Baraka has struck a very moderate tone during the campaign and doubt that he would do anything to damage the city’s fledging renaissance. Newark’s deputy mayor for economic development, Daniel Jennings, says, “I don’t see development slowing down no matter who wins. Both candidates are pro-growth.” Others are less sanguine. “This guy is as radical as they come,” one prominent business owner tells me. “He makes de Blasio look like Ronald Reagan.”

Jeffries has a new talking point in his effort to paint Baraka as anti-economic development. “We had a debate the other night,” Jeffries tells me. “He talked about five new taxes. He talked about a toll road on McCarter Highway [Newark’s main entry point]. I don’t know what world he is living in where he thinks that is going to force investment into Newark.” The communication director of the Baraka campaign, Frank Baraff, insists that Baraka was only “speaking hypothetically about possible ways to raise revenue for the city.”

Baraka doesn’t seem too concerned about his radical image. “People call me a radical. Well, we’ve got radical problems,” he said recently. But others disagree. “Newark stands at a crossroads. Newark needs a leader who solves problems, not someone who throws bricks," says Jeffries supporter Councilman Anibal Ramos Jr. "Newark needs a chief executive officer, not a protester-in-chief."

Whether Newark chooses the moderate and measured Jeffries or the fiery and flamboyant Baraka, there is cause for optimism. Although Newark faces enormous challenges, there are green shoots sprouting up all over the city. One hopes they will be nurtured and continue to grow, whichever candidate emerges victorious next Tuesday.

Correction: This story has been updated to show that Newark's unemployment rate is 13%, not 14% as originally reported.