In response to the deadly riots in Charlottesville, Virginia, this month, President Donald Trump said, “We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence on many sides. On many sides.” Trump’s failure to directly condemn white supremacists and neo-Nazis came on the heels of his travel ban on people from seven Muslim-predominant countries, and his desire to build a wall on our southern border to keep out the “bad hombres.”

Though it has dominated headlines, few are noticing that identical events followed a book published 100 years ago. It was arguably the most dangerous scientific treatise ever written. And in it is the one phenomenon that ties all of these events together.

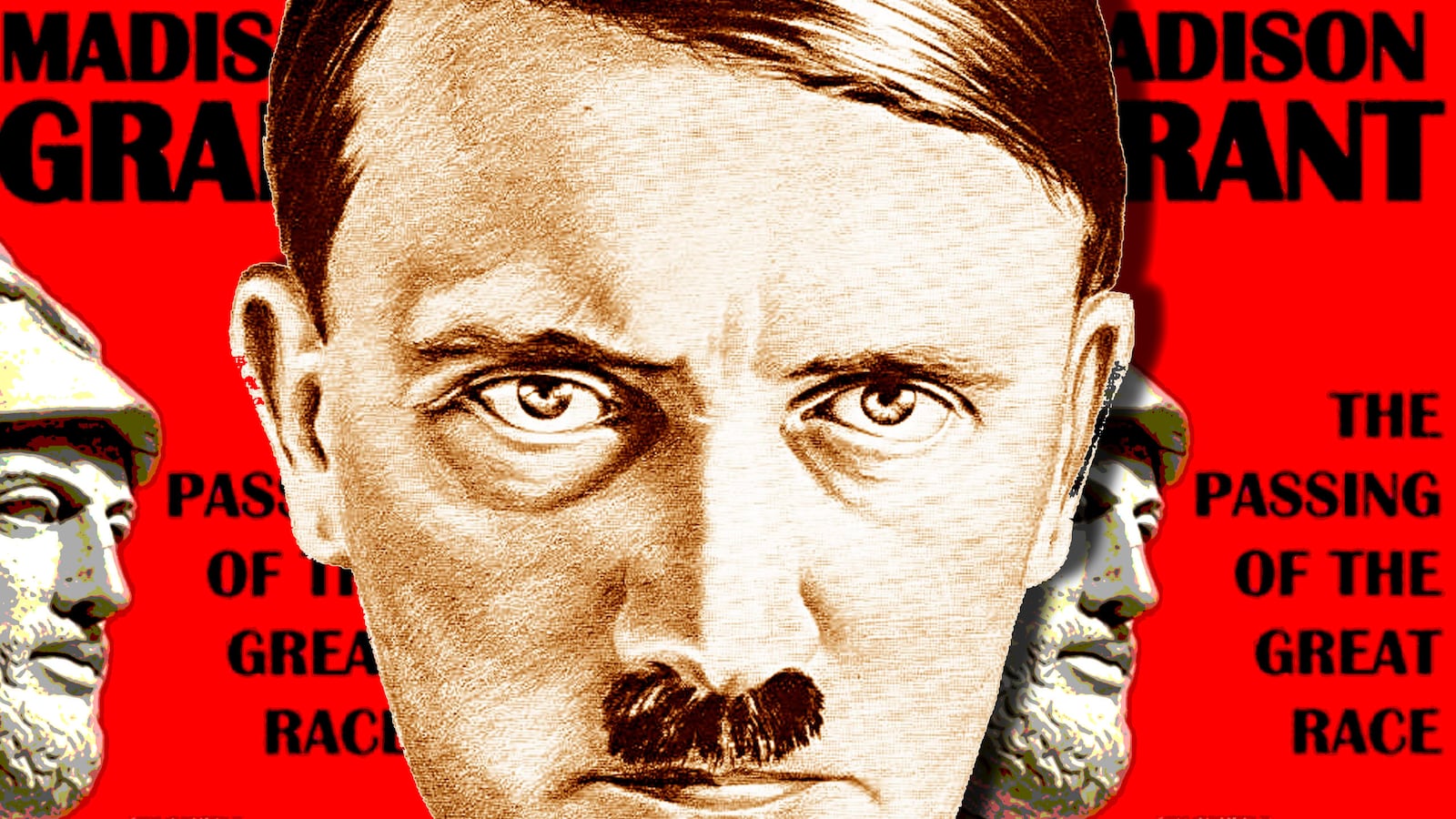

In 1916, Madison Grant, a New York City conservationist and lawyer, published The Passing of the Great Race. It was an extension of popular eugenic theories first proposed by Francis Galton, a British scientist and half-cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton believed that selective breeding shouldn’t be limited to animals. He argued that if we could breed faster horses, we should be able to breed better people, too. He claimed that traits like intelligence, loyalty, bravery, and honesty were also inherited.

In The Passing of the Great Race, Grant took Galton’s theories one step further. Using population movements, facial features, and pseudoscience, Grant argued that undesirable traits were passed not only from one family member to another, but within certain ethnic backgrounds and religious groups.

America, he argued, was committing “race suicide.” No longer were immigrants coming from “desirable” parts of northwestern Europe like the British Isles, Scandinavia, and Germany; they were coming from lesser countries in Southern and Eastern Europe. First published in the spring of 1916, The Passing of the Great Race was reprinted in 1922, 1923, 1924, 1926, 1930, 1932, and 1936, selling more than a million copies—arguably, one of the most popular scientific tracts in history.

In 1917—one year after Grant published his book—Congress passed a law banning “all idiots, imbeciles, feebleminded persons, epileptics, insane persons, [and] persons of constitutional psychopathic inferiority” from entering the U.S. During deliberations, one congressman read directly from The Passing of the Great Race. As a consequence, about 1,500 immigrants a year were denied entrance. One ardent eugenicist wrote a letter to Grant urging him to build a Great Wall: “Can we build a wall high enough around this country so as to keep out these cheaper races; or will it be a feeble dam, leaving it to our descendants to abandon the country to blacks, browns, and yellows.”

In 1921, Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act, which limited the number of immigrants to no more than 3 percent of the number of people originally from that country residing in America. In the year prior, some 800,000 immigrants entered the United States; the year after it was enacted, that number was reduced to 300,000.

In 1924, Congress passed the Immigration Restriction Act, which limited Africans and banned Arabs and Asians outright. After 1924, the number of immigrants permitted to enter the United States every year was cut to 20,000.

In 1929, Congress passed the National Origins Act, further restricting immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Because of these laws, more immigrants came into the United States in 1907 alone than during the entire next quarter-century.

Madison Grant was thrilled. “[This is] one of the greatest steps forward in the history of this country,” he said, according to Jonathan Peter Spiro’s book, Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. “We have closed the doors just in time to prevent our Nordic population from being overrun by the lower races.” The director of Ellis Island, the entry point for most European immigrants, commented that immigrants were starting to look more like Americans.

Ten years after The Passing of the Great Race was published, it was translated into German, the language in which a disgruntled corporal—recently imprisoned for his part in a riot in Bavaria—read it. After finishing it, he sent a letter to Madison Grant. “This book is my Bible,” he wrote. The soldier later included whole sections of Grant’s book in his own book, Mein Kampf. What Grant had called the Nordic race, Adolf Hitler called the Aryan race.

To say that The Passing of the Great Race had influenced Mein Kampf would be an understatement; in some sections, Hitler had virtually plagiarized Grant’s book. For example, in The Passing of the Great Race, Grant wrote, “It has taken us 50 years to learn that speaking English, wearing good clothes, and going to school and to church does not transform a Negro into a white man.” In Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote, “But it is a scarcely conceivable fallacy of thought to believe that a Negro or a Chinese, let us say, will turn into a German because he learns German and is willing to speak the German language.”

In 1936, three years after Adolf Hitler came to power, the Nazi party listed The Passing of the Great Race as essential reading. Grant’s “race suicide”—a fear that his Nordic race would be diluted out by “inferior” races—had become ethnic genocide. “National Socialism is nothing but applied biology,” said Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s deputy Führer. During the next decade, “race purity” would reach its hideous, illogical end.

Although neo-Nazis and white supremacists still laud The Passing of the Great Race in their literature and on their websites, the book has faded into darkness. Its lesson—that we are all members of one race, the human race—shouldn’t.

Paul A. Offit is a professor of pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The story of Madison Grant is adapted from his book, Pandora’s Lab: Seven Stories of Science Gone Wrong (National Geographic, April 2017)