In December 1806, two men got into an argument in Riley’s bookstore on lower Broadway in New York City. The younger of the two, then in his late twenties, insisted that Italian literature’s glory days were a thing of the distant past. The older man, middle-aged but tall and handsome (he still had all his own hair, though none of his own teeth), insisted that, on the contrary, if they stood there for a month, he could not enumerate all the stars of Italian writing. And by the way, did the young man know of anyone who needed a teacher of Italian?

There was plainly something persuasive about the eloquent stranger with the heavy Italian accent, because two days later he was holding forth on the glories of Italian literature and European culture generally in the mansion of the Episcopal bishop of New York, who was also the president of Columbia College and the father of the young man in the bookstore, whose name was Clement Clarke Moore. We remember him as the author of “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” aka “The Night Before Christmas.”

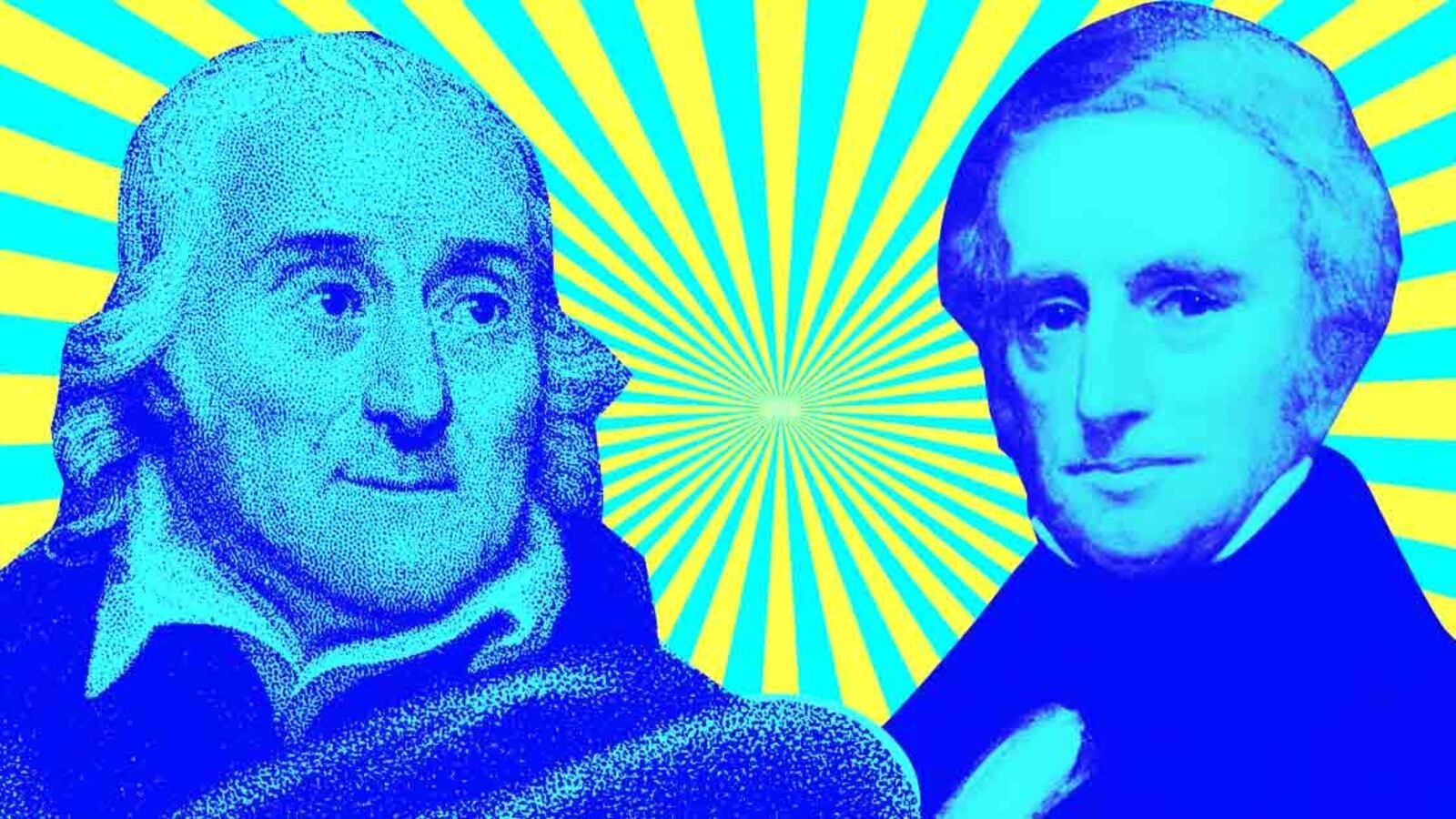

The older man, who stood there bragging about the boldfaced names with whom he’d caroused and worked in Europe, was Lorenzo da Ponte. To hear him tell it, he’d known the Austrian Emperor Joseph and the Emperor Leopold, and was friends with Casanova, and had collaborated with Mozart on not one but three operas.

Did the Moores ever investigate his outlandish claims? If they had, they would have discovered that while da Ponte was boastful, he was not a liar. If anything, given the storied nature of his life, he was being modest. Sooner or later, the Moores learned to believe da Ponte, so completely in fact that in time they helped secure him a position as the first professor of Italian at Columbia College. Clement would remain da Ponte’s friend and benefactor for more than 30 years, until da Ponte died in 1838 at the age of 89.

Though neither knew it at the time they met, one of them was on the way up, the other in decline. Besides being Bishop Moore’s son and a promising young professor of Classical and Oriental languages at Columbia, Moore was also the heir to his mother’s family’s considerable land holdings in Manhattan, which he subdivided and sold off as lots that make up what is now Chelsea.

Moore epitomized respectability. He was rich, pious, beneficent, and never touched by scandal, although he did own slaves until the state outlawed it, and was never afraid of fighting city hall. He complained when the city wanted to run a road through his property, and complained again when dunned for the cost of civic improvements to the land. But he was no Philistine: When the city wanted to destroy the winding streets of Greenwich Village and replace them with streets conforming to the grid, he wrote an anonymous pamphlet that must have been persuasive, because the plan was swiftly dropped. And he could be generous: Besides helping da Ponte find work for years, he had a long involvement with the city’s institute for the blind and donated the land on which the Episcopal General Theological Seminary still stands.

It is ironic then, that we remember him for a piece of verse that he would not even claim as his own for almost 20 years after it was published anonymously, because he did not want to be associated with such a trifle. (Or perhaps he was reluctant because the poem, as several textual scholars now argue, was not his to claim.)

Da Ponte, in contrast, was anything but respectable, at least until he came to America. His several-volume memoir, written near the end of his life, might well have been titled One Step Ahead of the Sheriff, because that was the leitmotif of his long and storied existence.

He was born a Jew in the Italian town of Ceneda in 1749, but while he was a teenager, his father converted the family to Catholicism in order to marry a Catholic woman. Da Ponte and his two younger brothers were seminary trained, and by the age of 21 he had been named professor of literature and at 24 was ordained a priest—the clerical gig was simply the price da Ponte paid for his seminary education; his real passion was for poetry, and, well, other things. Moving to Venice, then the red-hot-center of European licentiousness, he supported himself by teaching Latin, Italian, and French. He also took a mistress, with whom he fathered two children. So dissolute was his life—he was said to have lived in a brothel, where he organized “entertainments” for which he played the violin—that by 1779 he was tried and banished from Venice for 15 years.

Thereafter he rattled around Europe for a couple of years, dodging the law, his creditors, and any number of jealous husbands while he patched together an income by attaching himself to this royal court and that nobleman for patronage jobs as a writer. His skills as poet, script doctor, and translator eventually led him to Vienna, where he secured a post as librettist and translator for the city’s Italian Theatre. By 1786, he was collaborating with Mozart, for whom he wrote the libretti for three of the composer’s greatest operas: The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Cosi Fan Tutti.

Librettists then did not invent plots, they adapted existing works, but a glance at, for example, Beaumarchais’ then-successful play that inspired Cosi Fan Tutti shows how skillfully da Ponte trimmed and compressed the plot, wedding both drama and comedy to the composer’s music. His collaborations with Mozart reveal a writer who understands music as much as he understands words. Even the comic operas da Ponte wrote have an emotional layer unusual for farce, and the interlaced tragedy and dark comedy of Don Giovanni make it one of those works of art that demand a classification all their own.

There is something extremely personal about the operas da Ponte wrote with Mozart, too, and you don’t need to be Freud to see that da Ponte was drawing on his own life when he wrote the lyrics to stories about sticking it to the nobility, sexual infidelity, and the damnation of a libertine. Don Giovanni was plainly modeled on da Ponte’s pal Casanova, but surely the librettist was also thinking of himself as a soiled priest playing the fiddle for customers in a Venetian whorehouse. He knew a thing or two about debasement, just as he knew that the good people are never as good as you think, and the bad people never as bad. Otherwise he could not make us care so much about the Don.

Three months after the debut of the last of these collaborations, Cosi Fan Tutti, da Ponte’s chief patron, Emperor Joseph II, died. A year later, Mozart was gone as well, and da Ponte was cut loose again. Armed with a letter of recommendation from Joseph II written before his death, da Ponte set out for Paris to see Marie Antoinette, Joseph’s sister. But on the way, he got wind of the revolution that was about to cost the French queen her head and revised his travel plans. With his female companion, Nancy Grahl, and their four children, he headed for London instead.

There he supported himself again as a translator, an Italian teacher, a script doctor, and also as a grocer. He worked in London for most of a decade, until 1805, when the threat of debtor’s prison forced him once again to pull up stakes and move, this time to America.

Moving back and forth between Philadelphia and New York City, he tried, and failed, at a variety of jobs: In just his first couple of years in America, he ran a distillery, a carting business, more than one bookstore, and—again—a grocery. Imagine, he writes in a bittersweet passage in his memoirs, “how I must have laughed at myself every time my poet’s hand was called upon to weigh out two ounces of tea, or measure half a yard of ‘pigtail’ [chewing tobacco] now to a cobbler, now to a teamster.”

He was well into this series of commercial misadventures when he met Moore. Hooking up with the well-connected young New Yorker and his circle must have done wonders for da Ponte’s self-respect—here, at last, were people who appreciated him. Thanks to Moore, da Ponte would become not only the chief proselytizer for all things Italian in New York society but also the living embodiment of European refinement and culture. Unfortunately, none of that did much for da Ponte’s finances. He was by all accounts a genius as a teacher, but he often had trouble finding students, and he was always a terrible businessman. Moore helped where he could, but while there is no evidence that he ever gave up entirely on his improvident friend, we do know that many times da Ponte came very close to exhausting even Moore’s patience.

Of course, no one likes a whiner, but da Ponte was a man with something to whine about: One reason people looked skeptical when he ranted about his genius was because his greatest achievement was lost on them. Opera companies had been coming and going since the Colonial era, but Americans in the early 19th century did not know much about the genre, and, if possible, cared even less. So by the time da Ponte arrived in New York, the city had no major opera.

Da Ponte himself helped start New York’s first such company, which failed, of course. But that was near the very end of his life, and maybe by then he did not care so much. He had, after all, enjoyed at least one shining moment when his past came alive and he could turn to all his New World friends and say, See, it was neither a lie nor an exaggeration. I was merely telling you the truth.

That would have been the night in New York in May 1826 when a traveling European company mounted the first performance of Don Giovanni ever seen in America.

We know da Ponte attended the premier, because he had helped organize the production and exhorted everyone he knew to buy tickets. We know, too, that the audience was packed with his students and friends and famous acquaintances, such as James Fenimore Cooper. Was Moore there, too? Surely he must have been, wondering, like everyone else, what to expect before the overture began and the curtain rose. He had known da Ponte for years, and had spent hours listening to his friend carry on about Mozart. It must have all sounded impressive. But if you have never heard Don Giovanni, or much opera at all, what would you think? Well, here it was at last.

It is only speculation, but surely Clement Moore went away that night with a new appreciation for his friend, understanding at last that da Ponte could not only talk of the high culture of Europe but was himself an artist of the first rank, a collaborator on one of the world’s greatest works of art. How else to explain that in this same year da Ponte was at last named a full professor of Italian at Columbia, where Moore’s father had been president, and where Moore himself was still a professor and trustee.

As for da Ponte, surely he felt redeemed. Or was this night somewhat anticlimactic—a reminder that his greatest accomplishment lay years in the past? No, that was not likely, because all his life, da Ponte was a man who adapted himself to whatever circumstance he encountered. He had written words for Mozart, serenaded prostitutes, taught Italian to the wealthy young men of Manhattan, even run grocery stores. If ever there was a man who embodied the promise of his adopted country that one can reinvent oneself again and again, it was da Ponte, who once wrote, “I felt a sympathetic affection for the Americans. I pleased myself with the hope of finding happiness in a country which I thought free.” How else could he have found the energy, a few years hence, while in his eighties, to help start what would ultimately become New York’s Metropolitan Opera?

It’s a very American tale, this friendship of Moore and de Ponte. On one hand, we have a man of inherited wealth, his way greased by the power and position of his family, but also a man who believed in the public good (even if he didn’t like city hall telling him what to do with his property) and believed in helping struggling artists—and a man, yes, with enough twinkle in his soul to write the world’s most famous poem about Santa Claus—in the spirit of Christmas, let’s be generous and assume he was the author. And then you have a man on the run from his creditors and the law, a toothless, middle-aged immigrant who arrived in this country with little more than a beat-up violin and a few words of broken English. There was no compelling reason for them to have become friends. That was a thing of chance and luck. But it is safe to say that only in America could two such disparate individuals have come together and forged such a lifelong bond, a bond that was in its way as miraculous as the genius of Mozart or the existence of Santa Claus.