“Future ages will scarcely believe that one man adventured… to lay a foundation so broad and so undisguised for tyranny over a people fostered and fixed in principles of freedom.”

Or, put it another way, future ages won’t find it easy to understand how the hell a system specifically designed to eject the tyranny of kings has now allowed one into the White House. This week’s events have made it clearer than ever that President Trump has become King George III—without the taxes.

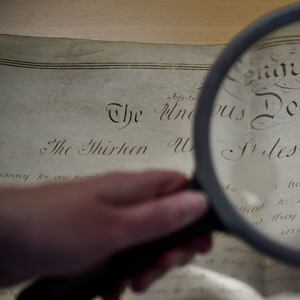

To rub home the irony, my opening quotation is from Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence, the definitive rejection of the rule of the British despot.

Those actual lines didn’t make it into the final version. “Tyranny” was already employed three times in the agreed version and Jefferson’s peers in the Philadelphia Congress probably decided that that was enough—but this deleted paragraph seems especially apt for our new tyrant. (The text is from Jefferson’s Notes of Proceedings—papers 1:315-19).

Indeed, it is chilling to realize how far Trump has already met the Jeffersonian definitions of a tyrant and despot: being heedless of laws, stripping officers of powers, repressing dissent, vilifying opponents.

And when it comes to racial preferences and bigotry, Jefferson, in another deleted section of the Declaration, could be speaking directly about Trump and the barbarity taking place on our southern border: “He has waged cruel war against nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of distant people who never offended him…”

To that can be added lines that did make it into the Declaration, that the King was “obstructing laws for the naturalization of foreigners, refusing to encourage migrations, made judges dependent on his will alone, sent hither swarms of new officers to harass our people, cut off our trade with parts of the world, altered fundamentally the forms of our government.”

To be fair, Trump has not actually “plundered our seas or ravaged our coasts” but he is willfully indifferent to the pollution of those seas and their increased propensity to flood our coasts.

To our ears part of the Declaration’s power lies in its antiquity of language, as in Shakespeare—“Prudence indeed will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes.”

Jefferson thought and wrote in the cadences of the Enlightenment. You can feel the moral outrage as his words hit the paper like red hot shot from a cannon.

The list of the monarch’s excesses are punctuated by direct personal censure: “A prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a tyrant is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.” (Jefferson added “free” in his revisions.)

The Declaration had no force in law. It was a mandate for revolution, written by a man who was not, to put it mildly, in the normal class of revolutionaries—he was among the top 1-percenters of the time, a cosmopolitan aristocrat with a scientific bent (and a slave owner with a black mistress.)

In places he wrestles with the decision to break from the British ties: “In every stage of these oppressions we have petitioned for redress in the most humble terms: our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injuries.” A more poignant sense of loss is conveyed in one of the deleted sections: “These facts have given the last stab to agonizing affection, and manly spirit bids us to renounce for ever these unfeeling brethren.”

And, we should remember, many were not swayed by Jefferson. They felt their self-interest was to remain loyal to the Crown. Just as, today, the Republicans have become the King’s party, believing that despite all his trespasses he will deliver their agenda which is principally, as defined by Moscow Mitch, to become a permanent Republican majority.

In this they behave in a way that was nailed by the man who was one of Jefferson’s inspirations, Tom Paine, an Englishman of far humbler background who brought to America a mastery of revolutionary polemic.

In his pamphlet Common Sense Paine attacked the “men of passive tempers” who looked “somewhat lightly over the offences of Britain.” If you were one of them, Paine warned, “whatever your rank or title in life you have the heart of a coward, and the spirit of a sycophant.”

Of course, the Declaration rises well above polemic to become an incontestable indictment. It compresses the case against George III into a force and brevity that makes the Mueller Report look like a pit of slurry. At the same time it appeals to the spirit with high intentions, not low and mean assaults.

Language, in the hands of Jefferson, was more decisive than war in ending the tyranny, although war would follow. And so the question is, does language have the same power today as we confront the new tyrant?

If it does, the Democrats have yet to find it. Their candidates range in tone from the stridency of Senator Bernie Sanders to the deliberately anodyne Vice President Joe Biden. There is no eloquent fury to equal Jefferson’s.

And, watching warily over them on the sidelines is the epitome of civilized political discourse, former President Barack Obama, who is bound by convention not to attack a sitting president no matter how vile his language and flagrant his crimes.

By his very nature, Obama is a judicious balancer of arguments, a deliberative and fundamentally small “c” conservative as well as a subtle and reflective thinker. He has warned the candidates about getting out ahead of the public in radical ideas (like Medicare For All), saying: “Even as we push the envelope and we are bold in our vision we also have to be rooted in reality.”

We can only wonder what Obama really thinks about the reality of Trump – a president who goes out of his way to denigrate and destroy as many of his predecessor’s good works as he can. Is there an inner Jefferson in Obama remaining silent because of his iron self-discipline and innate decency?

But let’s face it. The problem with decency in a dirty political fight is that you can’t amp it up. By its very nature it’s temperate and reasoned. Whereas the coarse and brutish adversary has no constraints, he can keep accelerating the viciousness as Trump does.

And another reason why decency gets so readily drowned out is the unprecedented size and range of today’s media megaphone. Tweets, television and social media don’t respect or like calm, they like fever and work as a force multiplier for the extremes. While instant abuse goes viral, studied reason dies almost as soon as it is uttered.

In 1776 the word “broadcast” was an agricultural term for the casting of seeds. There was no way of instant messaging.

First copies of the Declaration of Independence were printed on the evening of July 4 by a Philadelphia printer, John Dunlap. They are known as the Dunlap Broadsides because they were printed on a poster-sized sheet on only one side. They were then dispatched to every colony at the fastest speed possible, the speed of a horse, and often read out to crowds. That took weeks.

As an appeal to rise up against the despot, that one sheet of paper had an effect way above the legal and technical offense of taxation without representation. The signing of the Declaration on July 4, 1776, ended any chance of compromise.

The nation that emerged from that trauma believed that it had permanently disposed of over-mighty monarchs. Two and a half centuries later it seems not.