When Spy, that much missed mélange of muckraking and gleeful malice, were throwing their annual party, a must-attend for media and even some rash targets, in the Puck Building on Lafayette, I had no idea the place was named for their great progenitor.

Puck, a humor magazine that was known for its cartoons of pointed political satire, was launched in St. Louis in 1871, but moved to New York a few years later to begin publishing out of the splendid steel-frame building in 1887. In its nearly three decades of publication, Puck made and unmade politicians, waged war on corruption, and tore ribbons off the tabloids, then known as “The Yellow Press.”

In the foreword to a new book on the magazine’s legacy, What Fools These Mortals Be: The Story of Puck, America’s First and Most Influential Magazine of Color Political Cartoons, Stephen Hess, a historian of the genre, observes, “It is hard to overestimate the political influence of Puck ... during the last two decades of the 19th Century. It was greater than all newspapers combined.”

A 1904 cover shows the emblematic scamp, Puck himself, leaning across from his building to shake hands with Teddy Roosevelt, one of the very few Republicans the magazine supported, to celebrate his re-election. That cover was by Joseph Keppler, Jr., one of Puck’s founders. Predecessors and inspirations of the mag included Britain’s Punch, which first published in 1841, and the Parisian Le Charivari, which was started a few years earlier and fielded a team of artists including JJ Grandville, Gustave Dore, Honore Daumier, and Paul Gavarni, of whom Degas said, “Gavarni is a great philosopher. He knew about women.”

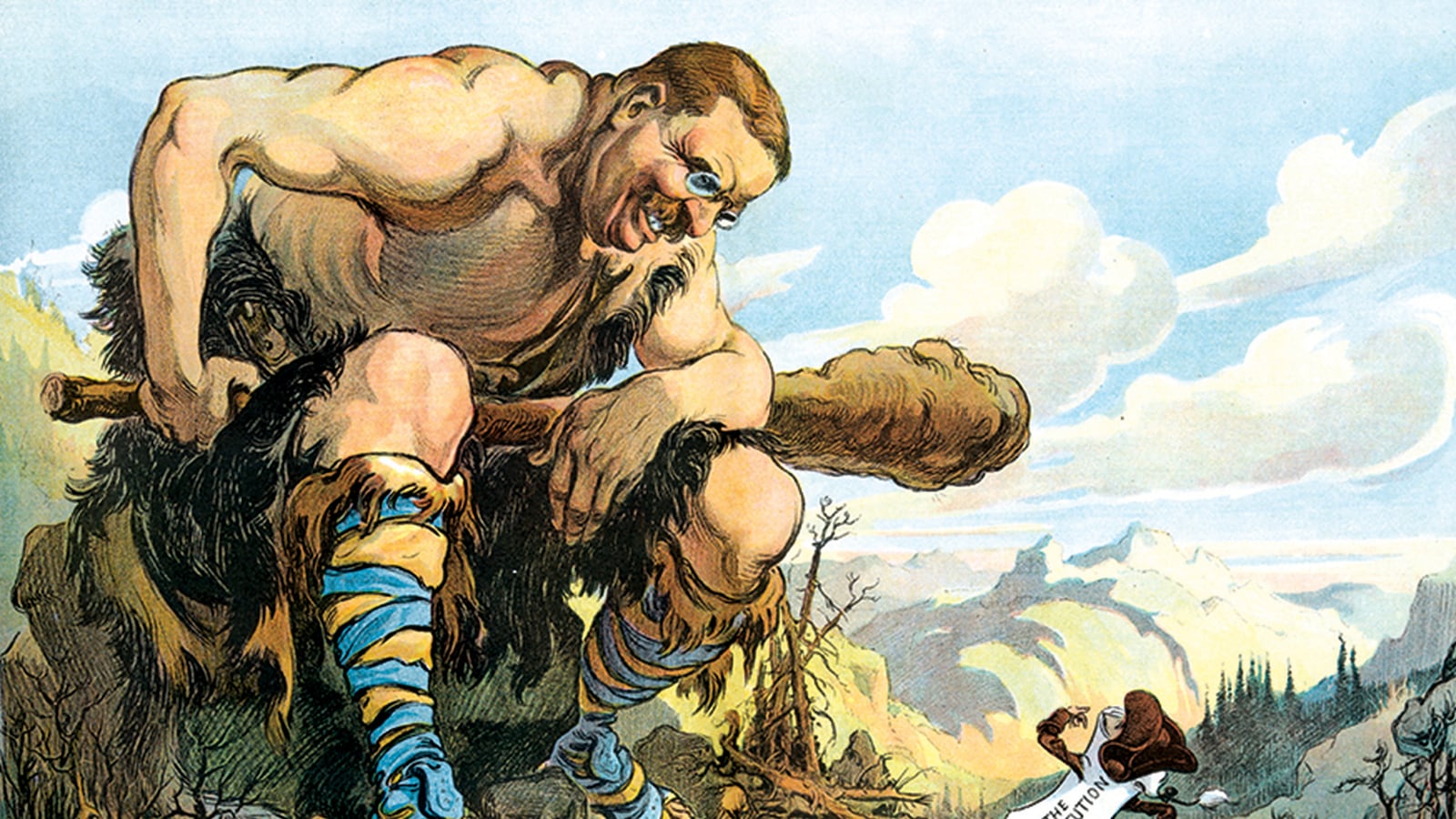

Puck artists, like their predecessors, combined picture-making skills with a caricatural precision and a knack for lethal symbols. Nast gave Boss Tweed a bulging moneybag for a head. Keppler’s advocate for Prohibition is a seedy figure, carrying a soda siphon, beset by angry women and growling dogs. His Standard Oil Company is a malign octopus. In Carl Edler Von Stur’s fashionista fable, The Mode and the Martyrs, a bird-headed woman’s hourglass figure is tightened by a figure with a death’s hood.

On some issues, Puck was so mired in its own times that the commentary is redundant. Among the comic scenes in A Female Suffrage Fancy, for instance, is one of a frazzle-haired fellow taking care of four brats and a boiling kettle, captioned Wife out Electioneering.

Usually, though, old-fashioned Liberalism is very much at the fore in Puck. Keppler shows Theodore Roosevelt welcoming Booker T. Washington to the White House, and Rose O’Neill, one of the publication’s only women illustrators, presents an elderly black man observing that at least in the days of slavery black folk were too valuable to be lynched. Another Keppler shows the actress Sarah Bernhardt confronting the churchy vultures who were attacking her for having a child without wedding bells.

Many of Puck’s issues remain bang up to date, if sometimes mutated. Louis Glackens shows Anthony Comstock, the anti-obscenity crusader, getting into a bath fully clothed, and then wearing monk’s robes and pursuing a poodle which, unlike the decent doggies, isn’t wearing knickers. The Puck illustrators would have found words and pictures for the anti-abortionists for sure.

Looking Backward, one of Keppler’s most famous cartoons at the time, shows five silk-hatted, potbellied fellows preventing an immigrant from getting off the boat. Behind their silk hats loom shadows of their immigrant forbears. Half of a Keppler published on January 9, 1884, shows virgin forest, the other half a smoking industrial slagscape. It was captioned Preserve Your Forests From Destruction And Protect Your Country From Floods And Drought. Yellowstone Park, the first national park, was then a dozen years old. I can all too easily see climate change deniers pointing a finger and chanting, “You see! Same Old, Same Old!”

And The Prize Is Death, a cartoon by Albert Levering, attacks an epidemic of reckless driving. It was published in 1910, a couple years after Ford introduced the Model T. In 1913, Will Crawford lampooned an early phenomenon of popular entertainment, Buffalo Bill’s Farewell Parade, because it had been lumbering on for three years. Only three years? Some veteran rockers won’t see the point of that one.

Some of the jests that appeared have been proven wrong-footed by the march of time, as one would expect, but a few have acquired a fresh point of view. One vignette in E. Opper The Collecting Mania (1899) shows a boy saying to his father of a classmate: “He’s got the biggest collection of cigarette cards of any boy in the school.” In another a man boasts, “What do you think of it, old boy? The finest collection of false faces in America!” His friend has dropped hat and cane in shock but the drawing shows stuff that an Americana collector nowadays would kill for.

So the images are splendid, right? Yes, but some observations. It’s no news that our journey into modern times has, for the most part seen humor, both in pictures and words, speeding up and stripping down. The sheer pictorialism of the Puck artists make their work a richer diet than we are used to. But What Fools These Mortals Be includes images that show the dawning of a new sensibility, like The Trail of the Serpent by the Mexican artist, M. de Zayas, and The Uses of Kultur by D. Gulbransson. These have the pared-down, Pre-Modernist look of Art Nouveau. Gulbransson also worked for the German magazine, Simplicissimus, where you can see High Victorianism being cleared away as efficiently as it was by Aubrey Beardsley in the contemporary Yellow Book.

Same thing in The Heavenly Porter, a visual joke by Louis Glackens about Halley’s Comet. Glackens was a prolific cartoonist in Philadelphia and his comics are one of the most surprising elements in the Puck book. One strip, Foolish Grandpa and Sour Henry, shows Grandpa being hit on the head by a sandbag and blown up by dynamite. In the last frame Henry’s hat is being cleaved by a downwards moving axe. These nonchalant brutalities seem at first at odds with the genteel decorum that mostly cloaks late-19th century culture.

Glackens’s other pages feature similar dark hilarities. But there was a lot of raw violence in the humor of the time. It’s in the formerly famous German’s children’s book, Struwwelpeter, with the Scissor Man who snips of the thumbs of children who dare suck them. It’s in the British book, Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes of 1898. There had been a lot of such stuff available in the environment too. Not so long before, executions had been popular entertainment and trips to a madhouse were like going to the circus. But ahead lay the Great War. And ahead of that lay Dada.

Puck was a waning force by then. It went to black and white in 1916, died in 1918. It’s rather nice though that the name was carried over to a Hearst comics section. George Grosz is just one of the more eviscerating political penmen to have risen since, but he wasn’t a magazine man and no humor magazine has ever again enjoyed the political power of Puck in its prime. That has been ceded to other media. There’s a story of George Goursat, the French cartoonist, who drew as Sem, attending some posturing nightmare or other in the ‘thirties, the days of the dictators. Sketching alongside a fellow immortal, the Brit cartoonist, David Low, Goursat suddenly stood up, stacked away the tools of his trade, and snapped the box shut.

“We are not needed here, Mr Low,” he said. “Here the camera suffices.”

That was then. But the raw believability of, say, Magnum photography has been done for. Photoshop, on-line image manipulators and videogamers prevail. Time to open up Sem’s box again, I think.