One can argue about the greatest musical achievement ever overseen by legendary producer Rick Rubin (*cough* Slayer’s Reign in Blood *cough*), but there’s no denying his immense impact on the last four decades of popular music, be it in rock, country, or most famous of all, hip-hop, via his Def Jam Records label. Thus, he’s a deserving candidate for a laudatory tribute. Showtime’s Shangri-La, however, is more than that, functioning as a celebration of his guiding ethos as well as his oeuvre, both of which are intimately connected to Shangri-La Studios in Malibu, California, that he’s called his own (and virtual home) since 2007.

Alternately fascinating and frustrating, the four-part Shangri-La—directed by Won’t You Be My Neighbor?’s Morgan Neville and Jeff Malmberg, and premiering July 12—isn’t interested in chronological recitation; those looking for a timeline of Rubin’s triumphs will instead have to turn to Wikipedia. Rather, it’s an intimate snapshot of the master at work, which as one quickly learns, takes a most unconventional form. Known for his giant white beard and disinterest in shoes (this after he initially defined himself via a black beard and dark sunglasses), the 56-year-old producer moves with a Zen-like grace through the squeaky-clean Shangri-La, shepherding young and established artists alike to become their best selves by listening to their interior voices.

It’s a process that, per Rubin, requires that he become something like an absence, only providing guidance and encouragement when necessary, while fashioning a peaceful utopian environment—marked by stark white walls and furniture, and no TVs or decorations—that’s safe, free from distractions and conducive to turning inward. Rubin’s core philosophies about music and life involve being as open as possible to the new; taking risks rather than repeating yourself; and bravely following your instincts. To him, there’s nowhere better to accomplish those goals than Shangri-La, whose own mythology (replete with stories about Elvis, Bob Dylan and The Band, the last of which were furthered by Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz) dovetails with his own.

Rubin burst onto the national scene with the Beastie Boys, shepherded Run DMC, LL Cool J and Public Enemy to stardom, and then turned his attention to various other genres with phenomenal results, including classics with Slayer, Tom Petty (Wildflowers) and Johnny Cash (all six American Records albums). Today, he continues to collaborate with luminaries all across the musical spectrum, many of whom are seen in sequences throughout this Showtime series, including Tyler the Creator, SZA, Ezra Koenig of Vampire Weekend, and the late Mac Miller. Considerably more time is spent on Rubin partnering with a collection of younger artists who are, let’s just say, of lesser interest. Fortunately, Shangri-La locates intriguing sources of Rubin’s own inspiration in his love of both professional wrestling (and its emotional storytelling and real/unreal dynamics) and magic, the latter of which is no surprise given his career-long search for that mysterious spark that turns a good concept great.

Neville and Malmberg use animation and evocative imagery of burning suns and rolling waves to capture a sense of Rubin’s spirit, which is rooted in his devotion to Transcendental Meditation (TM)—a topic he chats about with fellow TM practitioner and proponent David Lynch. More captivating still is the show’s interest in the very thing that most music docs (and biopics) skip: the actual work of artistic creation. In scene after scene, Shangri-La depicts musicians, and Rubin, discussing songcraft, arrangements, and the motivations, feelings and ideas behind given compositions (“I’m in the maze,” groans a struggling Julian Casablancas at one point). It’s a rare, extended glimpse at the toil that goes into making something out of nothing, both inside and outside the studio, as Rubin and various artists concentrate on digging into what they’re doing, and why.

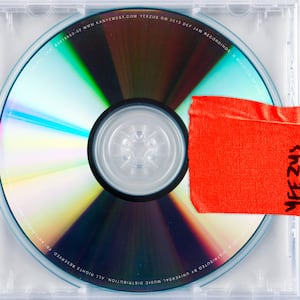

For such intimate access to Rubin, Neville and Malmberg clearly had to set aside any critical perspectives on their subject; there’s nary an unfavorable word spoken about anything related to the producer. That’s far less troublesome than the fact that Shangri-La skews so hard in favor of expressing Rubin’s TM-influenced views that it neglects quite a lot of his history. His founding of Def Jam in his NYU dorm room, and ensuing relationship with the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy, receives a moderate amount of attention courtesy of interviews between Rubin and, respectively, Mike D and Chuck D, as well as amusing dramatic recreations of his college entrepreneurial efforts, which were the partial basis for Krush Groove (in which he co-starred). But over the course of its four hours, the series does little more than briefly mention most of his other acclaimed projects—including his 2003 team-up with Jay-Z, The Black Album.

Even his seminal partnerships with the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Johnny Cash are only fleetingly addressed, so fixated is Shangri-La on Rubin’s way of thinking about his professional and personal beliefs. While Neville and Malmberg’s atypical non-fiction approach is initially refreshing, their disinterest in so much of the output that made Rubin a unique icon eventually becomes disheartening. Moreover, it results in repetition. Like the channel’s recent Wu-Tang: Of Mics and Men, Showtime’s latest music docuseries says everything it has to say by the conclusion of its third installment, and then self-indulgently meanders about during its closing chapter. Thanks to the appearance of Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo in episode four, who explains his chief role in first introducing Rubin to Shangri-La, there’s reason to stick with the show until its end—but only just barely.

If Shangri-La peters out before its conclusion, it nonetheless conveys the totality of Rubin’s minimalistic approach to artistic production, felt not only in Shangri-La’s design and atmosphere, but also in his sonic tactics, which have always been about stripping away unnecessary elements so the performer’s personality can shine through (“He gave the genre a haircut,” proclaims LL Cool J about Rubin’s hip-hop work). Neville and Malmberg recognize that Rubin is, first and foremost, a facilitator of invention, and one whose idiosyncratic method affords artists the freedom to be who they truly are. In the process, their portrait contends, it also allows him to be his genuine self.