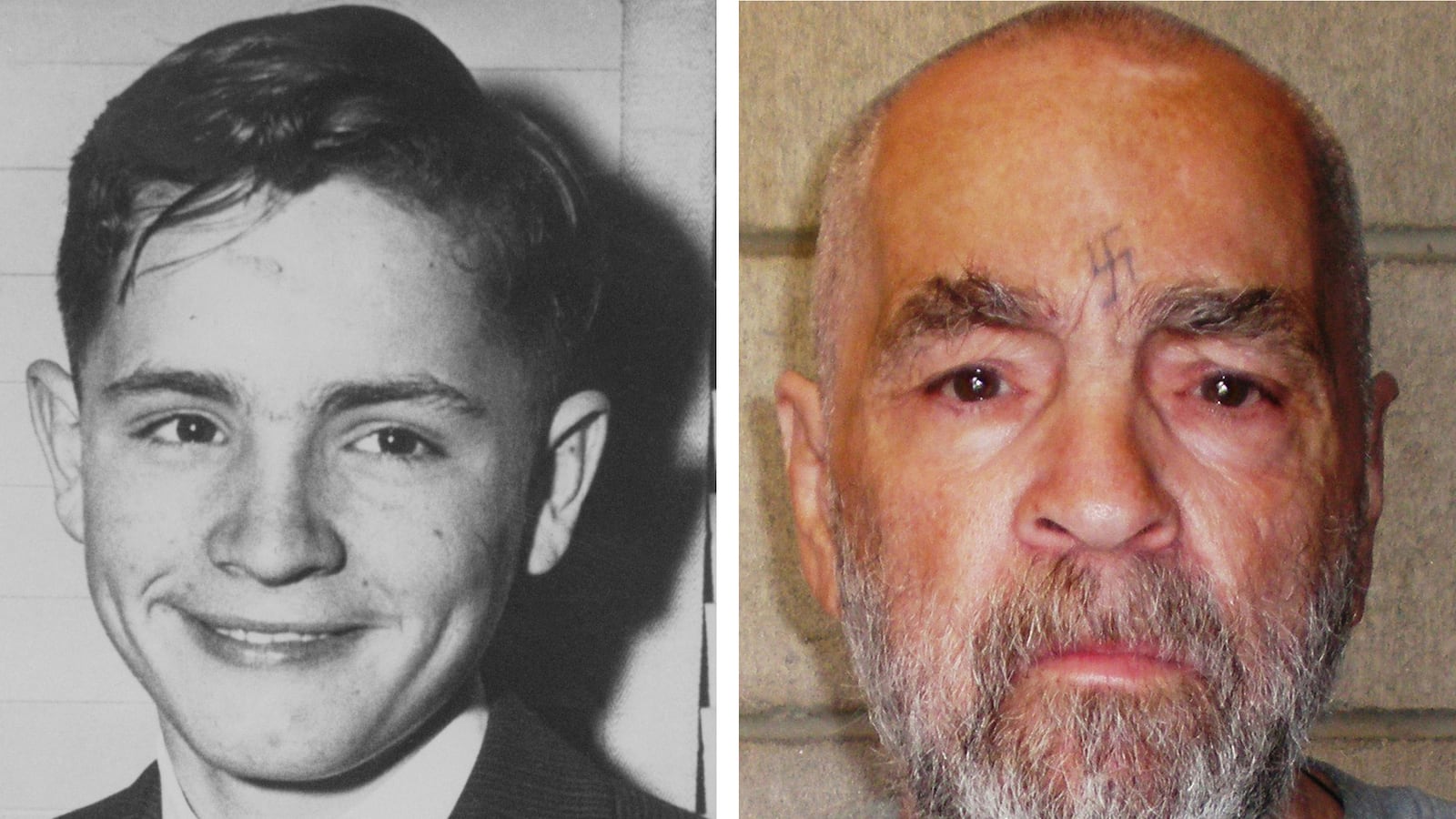

More than 40 years after the gruesome murders that made Charles Manson an infamous household name, perhaps enough time has passed finally to assess him as something other than a satanic incarnation of the darkest impulses unleashed by the turbulence of the 1960s. Jeff Guinn certainly thinks so. His chillingly matter-of-fact biography depicts Charlie (as Guinn belittlingly calls him throughout) as a garden-variety sociopath with above-average social skills, and as a lifelong predator whose early history reveals the typical profile of a small-time criminal.

Guinn’s principal source for the book’s new information is relatives who have not previously spoken to reporters, and they don’t paint a pretty picture. “Little Charlie Manson was a disagreeable child ... he lied about everything [and] always blamed someone else for his actions ... obsessed with being the center of attention ... he tried to manipulate everyone ... his interest in people was dictated by what they might be able to do for him.”

Granted, the odds were against a baby born to a 15-year-old girl more interested in partying than motherhood, one whose shenanigans earned her a five-year jail term for robbery when her son was 4. We quickly get the grim impression that Charlie’s destructive course through life was fixed very early. But we also see that he was no hapless victim of circumstance; he chose his path. A kid whose main interests were knives and guns was unlikely to grow up into a happy citizen, even if he was also fond of music.

Trying to put both their lives in order after she got out of jail, Charlie’s mother was unable to stop him from stealing and cutting school. In desperation, frightened by her out-of-control kid and his “crazy eyes,” she sent him to a Catholic school for male delinquents when he was 12. Over the next nine years, Charlie graduated from petty crimes and reform schools to transporting stolen cars across state lines, which earned him his first adult jail stint in 1956.

During his infrequent breaks from captivity in the 11 years that followed, Charlie acquired his only significant work experience as a pimp, applying to vulnerable young women the manipulative skills he’d honed from his jailhouse reading of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. Back in the penitentiary in 1964, he acquired a new goal after hearing the Beatles on the radio; he liked their music well enough, but what really impressed him was the adulation lavished on them by crowds of screaming girls.

Charlie developed the delusional belief that his minimal gifts as a singer-songwriter were finally going to get him all the attention he could ever want. Making it big in the music business was his plan when he was paroled in March 1967, but it was temporarily sidelined after he wandered into Haight-Ashbury and quickly realized that the California counterculture offered an irresistible hunting ground.

Over the next two and a half years, first in the Bay Area and then in Los Angeles, Charlie transformed himself from a two-bit hoodlum into a feared and revered guru whose slavishly devoted followers were willing to kill—and die—for him. Society and your parents have imprisoned you, he told the runaway girls he identified as prime prey among the hordes of kids drawn to California. You can become free “by giving everything up—possessions, individuality, ego.” His line of spiritual blather wasn’t much different from that spouted by every other street-corer guru in the Haight, but apparently he spouted it with extraordinary charisma and knew exactly what buttons to push with troubled, needy teenagers. They could leave behind their unsatisfying biological families, he said, “to become part of a real family, one that accepted and cherished them for who they were.”

Being part of “the Family,” as they began calling themselves in 1968, meant giving Charlie all your money and having sex with anyone he told you to, the latter being his means of acquiring male followers and making friends with the record-industry professionals he hoped would give him a contract. There’s a horrible fascination in watching Charlie cement his control over people by employing a creepy mixture of time-honored pimp tactics (alternating gestures of affection with “just enough beatings to remind them who was boss”) and the new tools provided by the counterculture: large quantities of drugs to dampen everyone’s inhibitions; group sex directed by Charlie to make sure there were no lasting attachments to anyone but him.

The atmosphere got even weirder and uglier as the Family grew larger and Charlie’s efforts to become a world-famous musician were met with universal indifference. Family women were forbidden to carry any money; everyone was commanded to carry a knife. At the evening LSD/preaching sessions, Charlie’s ranted about “Helter Skelter,” the impending racial uprising from which the Family would take refuge in a “bottomless pit” in the desert, to emerge as rulers after the new order self-destructed.

“At that point, we were little kitty cats who were mentally gone,” said Pat Krenwinkle. She had been Charlie’s third disciple, plucked from a chaotic home life in northern California and soon one of his truest believers. It didn’t even occur to her or Susan Atkins (disciple No. 4) to protest when Tex Watson, Charlie’s designated male leader for the excursion of August 9, 1969, told them they were going to kill everyone in the Cielo Drive house where a music producer who failed to appreciate Charlie’s genius had once lived. (Linda Kasabian, a more recent and squeamish recruit, was left to stand guard at the gate.) They didn’t know Sharon Tate or the four others they bloodily murdered that night, or Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, slain the next. It didn’t matter; it was all part of Charlie’s master plan.

Guinn is mercifully sparing with the gory details, though nothing can make them anything less than revolting. His coverage of the familiar material that follows, from the LAPD’s initially bungled investigation through the trial, differs from others primarily in the strong connections Guinn makes with Charlie’s past. The “Crazy Charlie” behavior that turned the courtroom into a circus was an act he’d perfected years ago in prison. His lifelong habit of blaming others reached its twisted apotheosis during the trial’s penalty phase following conviction, when his brainwashed female codefendants followed his orders to claim they’d done it all on their own and Charlie was innocent.

It’s frightening enough to think of Charles Manson as a lunatic product of the disordered, polarized 1960s. It’s even scarier to see him, as Guinn does, as a calculating opportunist who used the rhetoric of the times to further his lust for power and fame in the sickest possible ways. Manson is, as its author surely intended, deeply unsettling and unnerving.