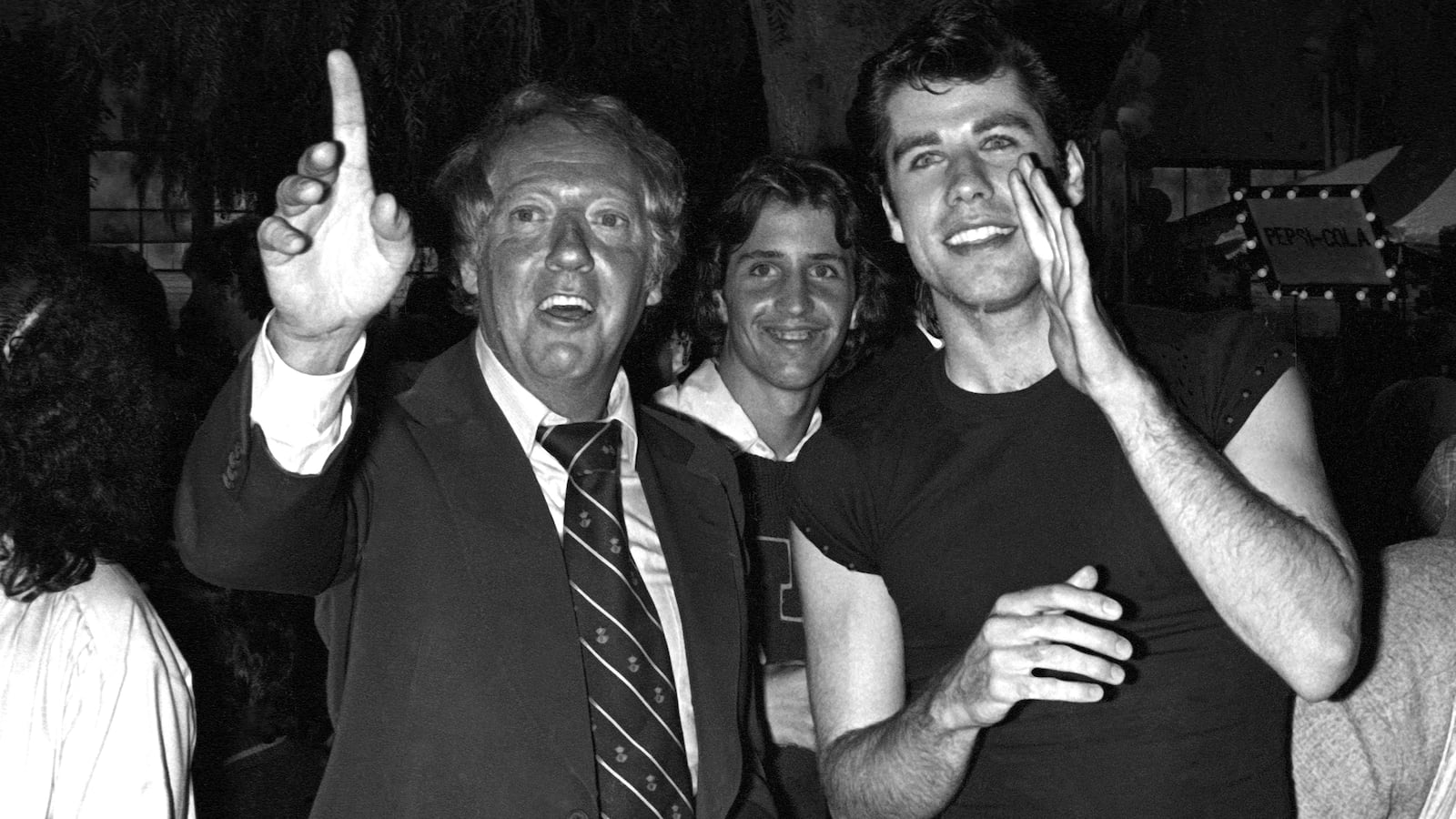

Robert Stigwood, the Australian manager/producer, who unleashed John Travolta and, arguably, ‘Discomania’ on the world, died on January 4 at 81.

Memory Lane time. I met Stigwood in London at the beginning of the 1970s, when he and Michael White, a British hyperactive theater producer, were bringing Oh, Calcutta! to London after a run Off Broadway.

Oh, Calcutta! was a musical revue, which focused on sex and combined nudity and thinkier stuff, being built from sketches written by, amongst others, Samuel Beckett.

So, as was the way of the time, it was porny but radical, and was naturally the hottest of hot tickets.

Michael White was a friend. I went to the opening and to the party, which was in Stigwood’s faux baronial mansion, poshed up with Old Master-ish paintings and stuffed animal heads. It was Haute Pop at its hautest.

Stigwood was ambitious, and had a streak of disruptive brilliance. It was he who, at Eric Clapton’s urging, plucked Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, and Eric Clapton from two groups he managed, put together Cream and sent them out to the States to open for the Who.

Cream swiftly became what has been called the world’s first supergroup, and ERIC CLAPTON IS GOD sprouted on walls all over London. And my King’s Road neighbor, Martin Sharp, who was renting Clapton’s studio, designed two of their album covers. How tiny London was then!

Soon Stigwood, an early maestro of what has become our simmering high/low cultural melt, morphed into movies. Jesus Christ Superstar was his first and it was followed by Tommy, which was based on a Who album and came out in 1975.

In Hollywood, Stigwood was seen as having a Midas touch.

The following year I was in New York working at New York magazine. There Stigwood was very much on the radar. Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night, a story by Nik Cohn, who had come over from the UK at roughly the same time, had been on the cover. Stigwood had bought the rights and it was now in production (it would become Saturday Night Fever). As was his rock-and-roll movie, Grease.

And he was putting together another ambitious movie, Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, based on you-know-what and starring Peter Frampton and the Bee Gees.

There were ironies about the Sergeant Pepper project. In 1967 Stigwood had become friendly with Brian Epstein, the Beatles manager, and had acquired a minority position in NEMS, which controlled the Beatles’ rights, thereby becoming co-managing director. And heir in waiting.

“Brian wanted to retire to Spain,” Stigwood told me. “He gave me the option to acquire control for…I think it was half a million.”

Brian Epstein OD’d a year later. Stigwood tried to follow through and Polygram came up with the moolah. But there was a problem. “He hadn’t told the Beatles about it,” Stigwood said. Adding, “I think that they were quite surprised.”

Right. Paul McCartney later told Greil Marcus the reaction of the group: “We said, ‘In fact, if you do, if you somehow manage to pull this off, we can promise you one thing. We will record ‘God Save the Queen’ for every single record we make from now on and we’ll sing it out of tune. That’s a promise. So if this guy buys us, that’s what he’s buying.’”

So that was a no go. But Stigwood had simply moved on, launching his own company, RSO, for Robert Stigwood Organisation. And he had signed three young Australians, the Gibb brothers, while he was at NEMS. The Bee Gees. They were soon topping the charts.

The premiere of Saturday Night Fever on December 16, 1978 was followed by a dinner at the Tavern on the Green, after which all moved on to a recently opened discotheque, Studio 54.

The movie was a huge, huge hit, and played a mighty part in the budding Discomania. It made Stigwood $100 million and the soundtrack sold above twenty million double albums. The wanna-be overlord of the Beatles was on top anyway.

Then Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band came out. It was critically eviscerated by all, and died.

Soon RSO too was history.

There have been curious elements in the trajectory of the phenomenon since.

Nik Cohn would unburden himself to the Brit paper, the Guardian, in 1994 to the effect that “Tony Manero,” the disco figure around whom he had built his piece had been a myth, literally, being based on a street-wise scenester he had known in London’s Shepherd’s Bush in the ‘60s.

As for Robert Stigwood, he would make further moves from time to time but his touch was gone. He died at a huge house on the Isle of Wight, just off Britain’s South Coast, attended, one hears, only by a retinue of staff.

Back when I was writing my magazine piece I was struck by the extent to which talented people disagreed about him. Michael Butler, who created Hair, just observed “Anything I have to say about Robert Stigwood is unprintable.”

A few, like Michael White, hit a nice balance. He still feels affection but, as he once wrote, at the end of the game, “The score always seems to read: Stigwood 3, The Rest 0.”