The speck of cosmic dust likely traveled for billions of years at more than 100,000 miles per hour before chancing into the Earth’s atmosphere and finally alighting on a rooftop at a community college in Minnesota.

The speck came to rest at longer-than-long last sometime between the construction of the college building roughly three decades ago and a moment in early October. That was when a 35-year-old Army combat veteran turned micrometeorite hunter named Scott Peterson used a magnet to collect it along with thousands of non-cosmic metallic particles of just plain dust.

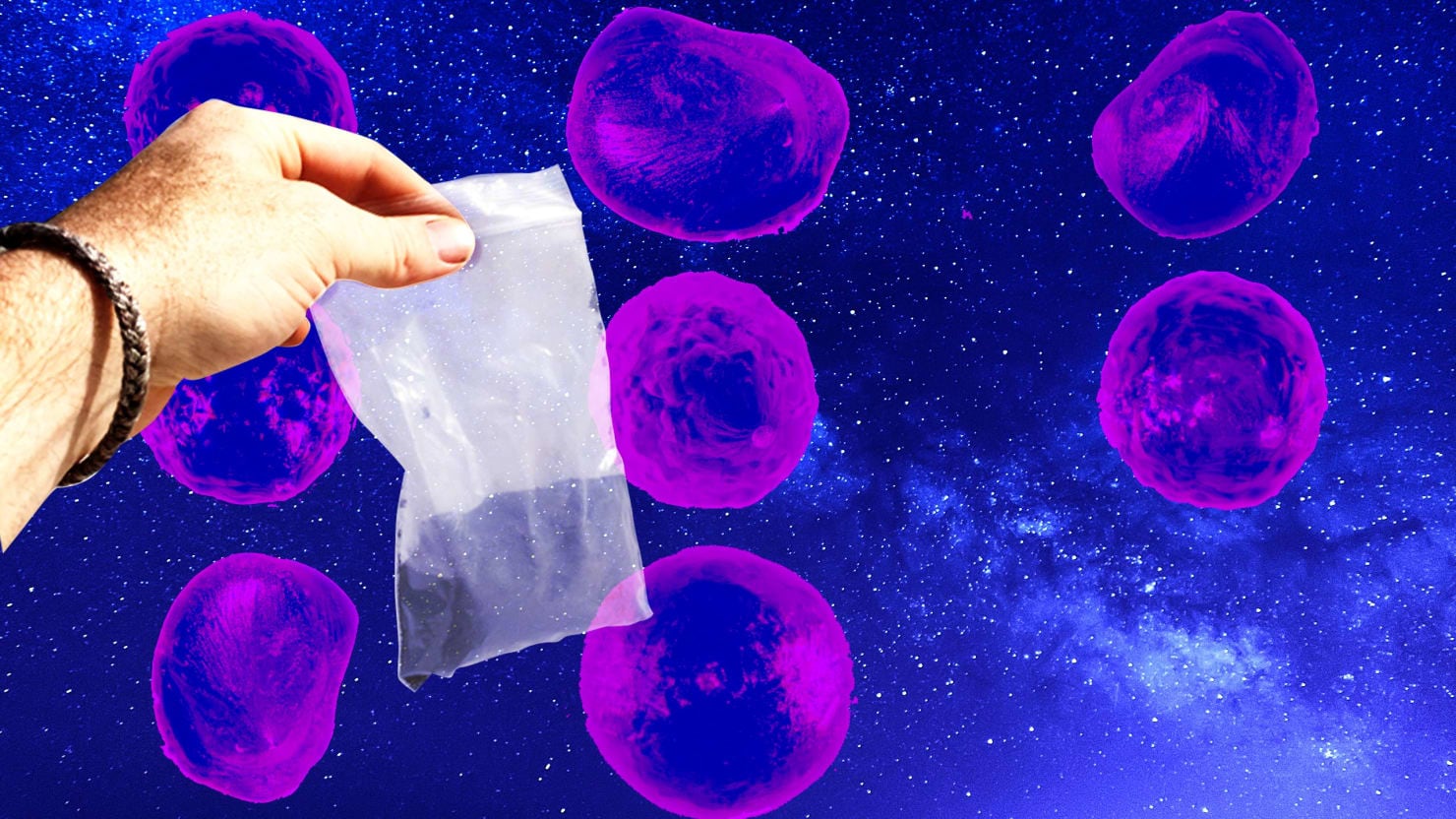

Peterson placed all the gathered particles into a plastic bag and brought them home, where he washed them and spread them on a sheet of tinfoil. He then put them in the oven at 200 degrees to dry, so as to hasten by a few minutes a hunt for an infinitesimal something that had been traveling before the first stirring of life on Earth, dating back to the birth of the solar system or perhaps even before.

“Just to make it quicker,” he later told The Daily Beast.

Peterson then sifted everything though a fine sieve, as micrometeorites are generally no larger four tenths of a millimeter. He spread the stuff in single layers on a strip of cellophane tape affixed adhesive-side up on a glass slide. He began to inspect them through a microscope.

Scientists have long figured that some 60 tons of cosmic dust falls to the Earth every day. The first known collection of micrometeorites was from the ocean floor by the Challenger expedition of 1872-76. The scientists aboard determined that the metallic particles they happened to find there were not likely man-made. The same reasoning was separately applied to remarkably similar particles found in sedimentary rock and in polar excavations. The chemical composition further suggested extraterrestrial origin and the shapes seemed to reflect the high temperatures generated while entering the atmosphere.

But in less remote places, the chances increased exponentially that particles were generated not by the birth of the solar system but by human activity. Scientists generally concurred that collecting micrometeorites from masses of mundane specks in settled areas was virtually impossible.

Then, in 2009, an infinitesimal glinting on an outdoor table caught the eye of a Norwegian jazz guitarist and amateur scientist named Jon Larsen. The source proved to be a fleck that felt metallic in his fingertips. He had an expansive enough imagination to wonder if it might have arrived in the outskirts of Oslo from deep space.

Larsen was inspired to search for other possible micrometeorites on rooftops and in gutters. His book In Search of Stardust describes how he used previously confirmed micrometeorites as a guide.

“To pick out one extraterrestrial particle among billions of others requires knowledge both about what to look for and what to disregard,” he wrote.

In February 2015, a particle that Larsen collected became what was described as “the first scientifically confirmed micrometeorite collected from a populated area.” Some 500 more of his particles were confirmed by the end of the year.

And where scientists could not easily date exactly when the cosmic specks retrieved from the ocean floor or rock sediment or polar expanses reached Earth, the micrometeorites found on roofs and in gutters could have arrived no earlier than when the buildings in question were constructed.

Among those who became enchanted by the prospect of finding cosmic dust amidst the everyday bustle was Scott Peterson of Brooklyn Park, Minnesota. He had been undergoing basic training in the Army on 9/11, and had subsequently come to appreciate fully the tranquility of the stars while gazing into the night skies from battlefields.

“It’s kind of like a little bit of peace when you’re in a war zone,” he told The Daily Beast. “You look up even during the worst times and it’s beautiful up there, no matter what.”

Peterson had been among the first American soldiers into Afghanistan and then had at one point been the U.S. soldier furthest into Iraq. Afghanistan was preferable to Iraq when it came to stargazing.

“No lights,” he said, noting that this meant no light pollution to dim the serene magnificence overhead.

Upon his return home, Peterson studied architecture and engineering and then physics. He took particular interest when he read online about Larsen and the micrometeorites.

In the first week of October, Peterson asked the folks at North Hennepin Community College in Brooklyn Park to let him go up on a roof to collect possible micrometeorites. The folks there were as surprised as might be expected, but gave him permission. He drew curious gazes as he set to collecting dust.

“They look at me like I’m a weirdo, but I’m up there anyway,” Peterson told The Daily Beast.

He spent maybe two hours gathering, and returned home to wash and dry and sift what he had collected. He became adept at using tweezers to place the miniscule particles on a glass slide.

“I’ve gotten pretty skilled,” he said. “I’m pretty good at it.”

For two weeks, Peterson examined speck after speck after speck under the microscope, comparing them to photos of what Larsen had confirmed as micrometeorites.

“Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t,” he told himself when he came upon a promising find.

Peterson took photos of it and sent them to Larsen, who soon replied.

“He was like, ‘Yep, that’s one,’” Peterson recalled.

The confirmed cosmic speck had been traveling for billions of years, then landed sometime after the community college was built some 30 years ago.

“And some schmuck from Minnesota goes on a roof and finds it,” Peterson marveled to The Daily Beast.

For all he knew, the speck’s journey had ended just a heartbeat before he collected it. The timing was so unimaginably random as to seem almost not random at all.

“Its sole purpose, all the atoms and coming together and traveling directly toward Minnesota,” Peterson said. “It’s amazing.”

He of course wanted to find more micrometeorites. He returned to the roof and did indeed harvest another, this one studded with infinitesimal nodules from when it was melted and some micro-micro elements continued moving while the rest of it slowed and cooled.

“It’s got the little spikes all over it,” Peterson told The Daily Beast.

In the last week of October, another visit resulted in another possible find, which Peterson would have felt sure to be a micrometeorite had it not been unusually micro, a tenth of a milimeter when they are usually not smaller than twice that size. He will hold off confirmation until scientific testing in December.

“I’ll keep my fingers crossed,” he said.

He has in most recent days collected atop the roof of a recreation center in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. He has also collected from the roof of the Wayzata Bay Car Wash in Wayzata, Minnesota.

“This guy was pretty interested,” Peterson said of the car wash owner.

Peterson is sure that he could easily win over any doubters.

“If I could invite them back to my house and show them under a microscope, I think they’d understand,” he said.

Even his wife, Kelly Peterson, is getting interested. She initially deemed his cosmic dust obsession to be a bit silly, but she now found herself pointing to a building.

“She said, ‘You should go up on that roof,’” Peterson reported.

Yet, for all his excitement over the cosmic specks that traveled billions of years to land in Minnesota, the biggest thrill by far for both him and his wife is their baby son, Everett.

The boy had a difficult birth and spent his first days in a neonatal intensive care unit, a period of time that by this measure was an eternity. He turned nine months old on Wednesday, a momentous milestone that offers another lesson in time’s relativity with regards not just to the speed of light but to the depths of love.

“Before I had a baby, I’d say, ‘Why do you guys count months?’” he told The Daily Beast.

Peterson reported, “He’s starting to crawl now.”

Peterson figures that before too very long he and his son will go hunting together for cosmic specks whose age in months is twelve times however many billion years.

“It’s going to be fun, me and him together searching for them,” Peterson said. “Me and him are going to do tons of science. I can’t wait for it.”

Peterson said that Everett has already shown some interest in the microscope.

“He kind of grabs at the eyepiece.”

Peterson figures that Everett will soon be taking a peek through it. A boy who makes each minute wondrously new will behold a past so distant as to defy imagining, the two measures of time bracketing everything for which a former warrior turned amateur scientist and full-hearted dad is thankful every day.

“He’s going to love it,” Peterson said.