CHILAPA DE ÁLVAREZ, Mexico — It’s a little past 10 o’clock on a Thursday night, and the last taco vendors in Chilapa’s central park are packing up to go home—but the cartel assassin known as “El Chimino” has just started his late shift.

Rival gang members, striking deep into his boss’s territory, now pose a growing threat—and Chimino must hunt down the competition.

He cruises methodically around the park tonight, using a cartel-owned taxi for cover. He’s accompanied by two more hitmen under his command, their weapons stashed beneath the seats. At major intersections the driver parks in the shadows between streetlights, and the men recon the town square on foot. The invaders call themselves the Ardillos (squirrels), and they’ve already murdered many of Chimino’s band. His orders from the boss: to attack on sight.

ADVERTISEMENT

The team completes its sweep of the streets around the park, then settles on a corner outside a 24-hour convenience store. From the new vantage point the squad commands an unobstructed view of the whole downtown, and Chimino can keep an eye on what’s happening while he talks to this interviewer—whom the enforcer insists on referring to as pinche güero, or “fucking white boy.”

“We don’t see too many güeros around here,” Chimino says, as I fumble for my notebook. “I hope nobody cuts your head off by accident.”

Finding Chimino wasn’t easy. Interviews between journalists and cartel sicarios (hitmen) aren’t all that rare, but most of the time they take place in the relative safety of a Mexican prison, after the killer has been incarcerated for his crimes.

I’ve spent the last several days wandering the bleak streets of Chilapa, pestering priests, aid workers, and store owners in the hopes of landing a face-to-face meeting with a foot soldier for the infamous Los Rojos cartel. Finally I catch a break, when a cabbie tells me about a fellow taxi driver who works as a scout under a man named Chimino who, I am told, is a sicario loco.

The cabbie offers to set up a rendezvous for later that night, although he makes it clear he won’t be responsible for my safety. When I phone a Mexican journalist, to ask for advice, I’m warned, “Los Rojos se maten por deporte”—“Rojos kill for sport.”

The narco slugfest over Chilapa makes for a slowly growing wasteland of shuttered shops and crumbling homes. During the day, newly widowed mothers tote starving infants about in their shawls, begging table to table in the town’s few remaining cafés. It’s unsafe to travel the roads after sundown, and public places don’t stay open past 10 at night. So, I have to meet Chimino on his own terms.

But the hitman’s story seems worth the risk. Chilapa happens to be a vital crossroads shipping center at the base of the Sierra Madre del Sur. Whichever faction holds the town also controls the exit routes for both raw opium gum and processed heroin coming down from the mountains. Since a single kilo of gum can fetch as much as 15,000 pesos ($975 U.S.) on the black market in Mexico, and a kilo of heroin as much as 40,000 pesos ($2,600), the struggle for Chilapa is as lucrative as it is bloody.

In the last year-and-a-half, scores of local residents were shot, decapitated, stabbed to death, or burned alive. The cartel warfare in these foothills has led to a murder rate of 54 per 100,000—four times higher than Mexico’s average—making Chilapa pound-for-pound one of the most dangerous places in the country.

Aside from a brief prison term in a penitentiary, Chimino has lived his whole life in the embattled Mexican state of Guerrero, and at 25 he’s already a well-known figure in the regional underworld. He started out six years ago as a halcón (scout), and slowly worked his way up to the official rank of sicario for the Rojos. Now he’s a top lieutenant under the cartel’s notorious crime lord Zenén Nava Sánchez (aka El Chaparro).

“El Chaparro always worries about strangers in his territory,” Chimino tells me, and adds that paid informants were watching me since I arrived in town. His jefe is also backed by formidable firepower. According to Chimino, Chilapa is the home base for 70 sicarios who carry AK47, M16s, automatic shotguns, and high-powered pistols.

“We’re everywhere at once,” he says, “but nowhere to be found.”

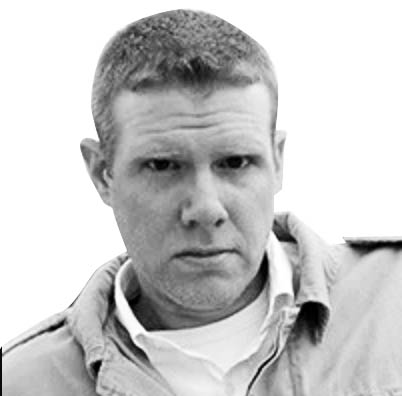

Chimino has a spikey haircut and a raised, finger-length scar under his left eye. There are more fresh scars on both forearms. He’s on the short side but heavily muscled through the chest and shoulders. With just the start of a paunch, he looks like a welterweight boxer who’s let himself go between bouts. He’s dressed tonight in the popular “narco polo” style: well-worn but expensive jeans, a printed sports shirt, and the black, outer-stitched shoes called apaches. Just standing still he gives off a powerful, menacing energy, as if even he’s not sure what he might do next.

“Tell me what it is you want to know, white boy,” says Chimino (who requested that only his cartel code name be used, to protect his identity).

I ask about the conflict between his syndicate and the Ardillos, an upstart group challenging the Rojos’ dominance of the drug trade, and he answers in rapid, slang-laced Spanish:

“The Ardillos whores attack us, because they want the town for themselves,” Chimino says. “They’re also out for revenge because we’ve ‘disappeared’ so many of their people. But the pricks do the same thing to us. So it’s all fair the way I see it.”

When I ask how many people he’s killed for the cartel, Chimino says there have been so many he no longer recalls the exact number. I ask him to estimate, and he says it’s “at least several dozen.” Then he pats me on the shoulder. “You want to be next?”

A Sinoloa-based network called the Beltran Leyva Organization (BLO) established the Rojos as a regional enforcement wing in the late 2000s. Upon arriving in Chilapa the cartel took control of the valuable opium trade in the sierra, putting taxi drivers on the payroll as scouts, policemen as accomplices, and even funding election campaigns for politicians.

But in the last few years, competition and federal prosecution weakened the BLO, and its leaders were either gunned down or arrested—opening the way to intensified turf battles. By the end of 2013, another BLO splinter cell, the Ardillos, was strong enough to threaten the Rojos’ hold over the narcotics production centers around Chilapa. The factions have been going head to head ever since, with neutral bystanders often caught in the crossfire.

“The Ardillos kill our men, but they also go after civilians,” Chimino says, when I ask him how the two factions differ. “The bastards even target women. They killed a girl, a waitress who was a spy for us. Those assholes tortured her for information and then they shot her. We can’t forgive something like that.”

For their part, the Ardillos claim Chimino’s outfit has murdered more than 30 of their members so far in 2015. But they’ve struck back hard in recent months, bolstered in part by powerful political connections—in fact, the Ardillos chief’s brother is president of the state Congress. A mayoral candidate with alleged ties to the Rojos was assassinated by rival gangsters in broad daylight after an election speech on May 2. But that was just foreshadowing for what came next.

From May 9-14, Chilapa was the scene of a cartel battle royal, as some 300 Ardillo-backed gunmen occupied the town, disarmed the municipal police, and proceeded to hunt down their competitors—or anyone else who got in their way. Dozens of innocent townsfolk went missing during the raid, including students and human-rights workers. Bodies have been turning up in the hills around town ever since.

Official estimates for the number of victims killed or abducted during five days of gang rule range from 16 to 30. But the Morelos Center, a human-rights NGO based in Chilapa, says the actual count could be much higher, with many families too fearful to report missing loved ones after receiving death threats.

Because police officers willingly surrendered to the Ardillos at the beginning of the occupation—and military units subsequently failed to intervene—the case has drawn comparisons to the mass kidnapping of 43 students last September in the nearby community of Iguala.

“It was like a goddamned invasion,” Chimino tells me, as he leans against the scout taxi parked at the curb. “The Ardillos hired a bunch of vigilantes to fight for them, so they outnumbered us. They captured some of our boys, and beat others real bad.” He calls over one of his men to show me the wounds on his face and scalp.

Chimino believes all of the missing to be “long dead by now”—whether they were affiliated with the Rojos or not. “But it isn’t over yet,” he says. “We’re going to pay [the Ardillos] back.”

At that point, another squad of Rojos passes by the street-corner observation post, whispering briefly with Chimino before moving on. Later, a truckload of Mexican soldiers zooms past us, their M4s at the ready. Chimino’s men don’t even flinch.

Chimino seems eager, almost proud, to talk about his work as an assassin for the cartel—like the lonely enthusiast of some arcane hobby who’s finally found an audience.

“I like to wait until a fool is alone, and then take him by surprise,” he says. “I’ll throw the pig down by the hair without compassion and put my foot in his back and a knife at his throat.” He slices the air with his hands as he talks.

“Then I knock his head with a pistol butt, hard enough to stun him, and we put him in the back of el vehiculo.” Chimino whacks the death cab’s trunk.

And then what happens?

Chimino: “So we take him someplace else—someplace he won’t want to be—to interrogate him. And if he doesn’t answer, and we don’t have orders to hold him [for ransom]—then it’s over.”

You mean you kill him?

Chimino: Well, we start to do it slowly. Asking him questions all the time. And if he doesn’t answer—first we cut off a finger. Then another and another. Then his hands. His ears. His feet. Even his balls. And then, if he’s lucky, we shoot him.

Do they ever die from blood loss?

Chimino: That’s a good question, white boy. But no. Because we tie them up, at the pressure points, so they don’t bleed out too soon.

So what if they do talk? Can’t you let them go?

Chimino: No. When we snatch someone from [a rival cartel], it’s a sure thing we’re going to kill him. Sometimes the son of a whore will talk right away to get himself off the hook. But that’s not how it works. If we let them live, they can identify us.

What about the bodies?

Chimino: I like to cut them up into little pieces. Many pieces, so they’re easier to dispose of. Then we dig a grave in the hills, or burn them, or dump them in a river. If you cut them up small enough, it’s easy to make [the bodies] disappear.

Aside from your cartel enemies—who else is a potential target?

Chimino: Fools like you. Any motherfucker who sticks his nose in our zone. The boss, he pays us by the head.

Just how much do you get paid?

Chimino: “If El Chaparro gives the orders, we get ten thousand pesos ($650) for a job. When the pig is more important—like a cop or a politico —it can pay thirty thousand pesos ($1,950). It all depends on the circumstances. That’s good money, no?”

And how do you feel about all of this?

Chimino: [Frowning] Such a question. I don’t even know how to answer that one.

Like many other poor young men in Mexico, Chimino first joined a cartel to “support his family,” including his mother and younger siblings. Before he was a killer for hire, Chimino painted houses—but with so many mouths to feed, he says, he couldn’t make ends meet. Compared to painting, his current occupation provides “a lot more money for a lot less work.”

He confesses to keeping an altar to Santa Muerta, the Saint of Death, in his house. He also admits to using illicit drugs—including cocaine and crystal meth—which he likes for the “crazy rush” they give him during confrontations with mob rivals. In spite of the constant violence that surrounds him, Chimino claims he’s not afraid of dying.

“The only thing I don’t want is to get surprised by anybody out here, and end up getting wounded and sent to prison,” he grimaces. “Better if the fuckers straight up kill me, if it comes down to it.” When I ask if he has a wife, he shakes his head no. “That way nobody will miss me, or cry all the time when I die.”

As we’re talking, a Chevy Malibu painted burnt orange, with tinted glass and the decal of a bucking bronco on the rear windshield, rumbles up to the corner. Someone in the backseat waves at Chimino, and he trots over to the tricked-out car.

“Those are my comrades in arms,” he tells me, when he comes back. “They’re wondering what the hell I’m doing here with you. They’re thinking: Should we all get together and fuck up the white boy?” The orange Malibu eases back into traffic, and Chimino watches until it’s gone.

“Somos muy evidentes aqui,” the hitman says. “We’re very obvious out here.”

I say I don’t want to put him in any danger.

“The one who’s in danger—is you,” he says.

A few days later the DEA-backed Federal Police Commissioner will arrive from Mexico City, to meet with the families of the missing in Chilapas. The Commissioner’s press conference won’t last six minutes, and he’ll ignore all questions about the Ardillos’ political connections, or why police officers gave up their weapons to the gang.

Less than 24 hours after the Commissioner hightails it out of town, search dogs will discover a pair of dismembered corpses in yet another common grave near Chilapa—two more victims of the ongoing gang war between the Rojos and Ardillos.

Back on the corner in front of the convenience store, Chimino signals his men that it’s time to go. “We should get back out on patrol,” he dismisses me. “And you should get your white-boy ass out of here right now.”

“Is there anything else you’d like to tell our readers in the States?” This question sounds, even to my own ears, like something only a pinche güero would ask, yet it’s all I can think to say.

But the sicario looks thoughtful.

“The first time you do it, somebody puts the gun in your hand and says, ‘Kill him or I’ll kill you. It’s your life or his.’ They make you pull the trigger. And maybe you feel bad. But after the first time—it feels different.”

Before he slips back into the shadows, I ask Chimino what he means by “different.”

“After the first time,” he says, “you start to like it.”