Netflix’s The Midnight Gospel—the latest from Adventure Time mastermind Pendleton Ward and comedian and podcaster extraordinaire Duncan Trussell—is not an animated show that’s easily explained.

Over the course of eight euphorically insane episodes, this rollicking odyssey tells the story of Clancy, a pink-skinned young man in a hallucinatory alternate dimension known as “The Chromatic Ribbon” who uses a Universe Simulator to visit dying worlds, where he engages in virtual conversations that he then broadcasts throughout the cosmos via his popular “spacecast.” It’s a psychedelic romp through far-out worlds and farther-out discussions about health, happiness, grief, mortality, drugs and other heady topics, the catch being that these chats have been taken from Trussell’s real-world podcast, and given outrageous new fictional contexts.

It’s as weirdly original as it is profound—and unlike anything you’ve seen before.

Asked how he describes the series, Ward has a typically hilarious summation. “I’ve been sayin’ it’s like Indiana Jones if you stripped out the dialog and replaced it with a conversation about life and death and serenity…and jokes…and then replaced the visuals with wild cartoon shit and beautiful art…and added songs,” he opines via email, a day before the show’s streaming debut (today). Trussell, who contributed voice work on Adventure Time but is best known for The Duncan Trussell Family Hour podcast, concurs, stating that “there’s a magic in podcasting that you can’t quite capture if you’re stuck with 8 minutes in-between commercials. So it’s pairing that with wild apocalyptic adventure, which creates this comedic reality that can also turn poignant and psychedelic and entertaining.”

“The cute gore is candy…the conversation is medicine,” affirms Ward. “That analogy stinks though, cause Duncan is so funny. He’s the candy!”

It’s no coincidence, of course, that a show this trippy is premiering on 4/20. “That’s Duncan’s birthday! Everybody get nuts,” suggests Ward. An avowed proponent of psychedelics and weed (“I think it’s one of the great gifts the dimension we’re in has to offer people, when used responsibly”), Trussell remembers the moment Netflix executives first suggested dropping the series on the unofficial stoner holiday. “One of them said, ‘Duncan, what do you think about us putting the show out on 4/20?’ They knew, already, that I was going to be like, ‘You guys, I love you!!!’”

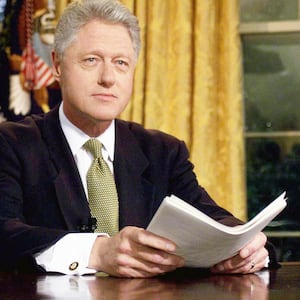

Fit for less-than-sober minds, The Midnight Gospel follows Clancy (voiced by Trussell) as he journeys to a variety of gonzo lands, beginning with an Earth overrun by zombies, which are combatted by the President of the United States—who, in this reality, is voiced by Dr. Drew Pinsky. As they fend off the undead, the two converse about legalizing narcotics, and the good/bad nature of drugs. The result is a parallel-narrative structure, with Duncan and Dr. Drew’s convo, and Clancy and the president’s action-horror mayhem, proceeding along simultaneous tracks. It is, to be honest, a lot to take in, and Ward admits that finding the right balance between the two took some time. “The beginning of production was a mad dash to refine the formula…of how much story to how much podcast conversation to how much action…finding places to rest…I wanted people to surf between the visuals and the conversation. It’s future television baby.”

Clancy’s tête-à-têtes cover everything from magic (with the West Memphis Three’s Damien Echols) to the “death-industrial complex” (with Caitlin Doughty). Choosing which to use was, according to Trussell, about highlighting revelatory moments from his career. “When I’m doing a podcast, there are moments where my whole universe changes because someone told me something that I never knew. Once you hear that, you’re forever changed; you live in a completely different dimension than you lived in before.”

Ward reveals that it was Trussell’s long-form audio chats that inspired him to return to TV animation following the stratospheric success of Adventure Time. “I had a desire to make something meaningful to me…somethin’ that dealt with compassion and kindness and that was funny. I was listening to Duncan's podcast and…realized he was doin’ somethin’ I wished I could be doin’. Duncan interviews meditation teachers and philosophers and sweet people who practice kindness, and because he's a comedian he makes listening and learning about that stuff really funny.”

For Trussell, the opportunity to collaborate with Ward was a no-brainer. “When I got an email from Pendleton, whom I’d never met, saying he listened to the Duncan Trussell Family Hour podcast, it was really wild, man. It’s like, holy shit, that guy made Adventure Time, one of the greatest animated series ever, and he’s listening to me? Whoa! That was wild. And over the years, we became friends.” When Ward reached out to discuss a possible partnership on the project that would become The Midnight Gospel, “my heart leapt in my chest, because I didn’t have any kind of idea that one day this podcast is going to be a psychedelic cartoon. I never would have thought it in a million years. It’s a podcast!”

That sort of unpredictability is central to The Midnight Gospel, which dances to its own idiosyncratic, synth-heavy tune. There’s an uninhibited verve to its on-screen action that’s in complete, if bizarre, harmony with its winding dialogues, the latter of which are punctuated by Trussell’s gift for uproariously unexpected comedic insights. Take, for example, the sixth episode, when Clancy has an epiphany about the true purpose of meditation—namely, that “It’s not like you’re supposed to shove some kind of butt plug in the asshole of your mind.”

Trussell’s perfectly absurd metaphor comes midway through his encounter with long-time meditation teacher David, whom the comedian has nothing but praise for. “It’s like a conversation you’d hear between someone who’s a very, very, very, very, very, very low-level person at a Shaolin temple, and a very high-level Shaolin teacher. That’s where I’m at in my spiritual practice; I can barely get my ass to sit still for five minutes straight, and David has this great patience,” Trussell chuckles. The aforementioned metaphor, then, is Clancy’s profane way of articulating his newfound recognition that meditation is about “not so much stopping [thoughts], and building a dam or butt-plugging them up, but letting them flow freely without you constantly reacting to whatever particular thought formation emerges that’s grabbing your attention.”

As befitting a series that’s overflowing with the crazy, grotesque, sexual and surreal, Clancy journeys to these expiring worlds via a Universe Simulator that looks like, well, a giant vagina. “That was just the first thing I thought of for a universe simulator. I’m more interested in hearing the Internet’s theories than injecting my own meaning into anything,” Ward states. Trussell, meanwhile, confesses, “If you look at it from a metaphysical perspective, everything that exists is in the progenitive womb of the universe. That’s what we’re in. We’re existing in a beautiful creative space that gives birth to stars, trees, squirrels, people and all the other things that we’ll never see or smell or touch or hear. So I think if you were going to make a bioorganic machine that simulates the universe, I think it would make more sense for that thing to look like a vagina than look like a dick.”

“A lot of people are like, man, it looks like a pussy. And I get it! Yeah, you’re right—it does!” he laughs. “But it’s not like we just sat around and said, what do you say we make it look like a pussy? There was some thought that went into it.”

There’s a method to all of The Midnight Gospel’s madness—be it spider-clowns and hungry hippos, or sentient piles of meat—even if it’s not always readily apparent. For Ward, however, the underlying criteria for fashioning loopy sci-fi contexts for Trussell’s podcasts was simple. “We were just havin’ fun. I think there might be reasons for why we did things but I have purged them from my memory. I’ve got a checkbox in my head for ‘Is this funny?’ and ‘Does the timing flow?’ And if I can check those then I can forget about anything else.”

While The Midnight Gospel invariably comes off sounding batshit bonkers, it has more to offer than just pandemonium, as evidenced, most movingly, by its closing episode, which is structured around Trussell’s podcast conversation with his mother Deneen Fendig shortly before she succumbed to cancer. For Ward, it’s the undeniable highlight of the series. “Every time I listen to that episode I reflect and learn something new about myself that helps me so much. I’m so proud to have been a part of its making. I hope people share that one with each other.”

It also, naturally, holds a special place in Trussell’s heart. “Pendleton is one of the most wonderful humans I’ve ever crossed paths with. He’s such a sweet person, and I can remember when he said, ‘The mom episode—we should do that,’” he recalls. “The thing with that interview is, she passed just a few weeks after that conversation, and I had listened to that podcast one time after she died, and that was with my wife after she found out she was pregnant with our son.” So difficult was it to revisit that interview that Trussell ceded responsibility for crafting the episode to the show’s ace animators. “To me, it’s one of the most mystical things, to see that the team of animators, who’ve never met my mother, and just from hearing her voice and seeing images of her, somehow transformed that into her spirit. I don’t understand it. It’s one of the great miracles of my life. Every time I watch it, I feel like I’m getting to spend a little bit of time with my mom again.”

More intellectually stimulating and poignant than its conceit suggests, The Midnight Gospel is part drugged-out fantasia, part philosophical rumination on life’s big questions—and thus bound to be different things to different people. Trussell, for one, is happy to let viewers discover their own interpretations. “I don’t want them to think there’s a right way to look at the show,” he cautions. “But that being said, in my own life, when I started doing the podcast and was much younger than I am now, I had a dad and a mom and two balls. Now I have one ball and no dad and no mom, because I got testicular cancer and my mom got breast cancer and my dad got COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] and passed away. In those encounters with truth, and not just those encounters, but every time I do an interview with someone who opens up to me, I have found that the world, in every single phase that it comes to you, has beauty in it. It’s there.”