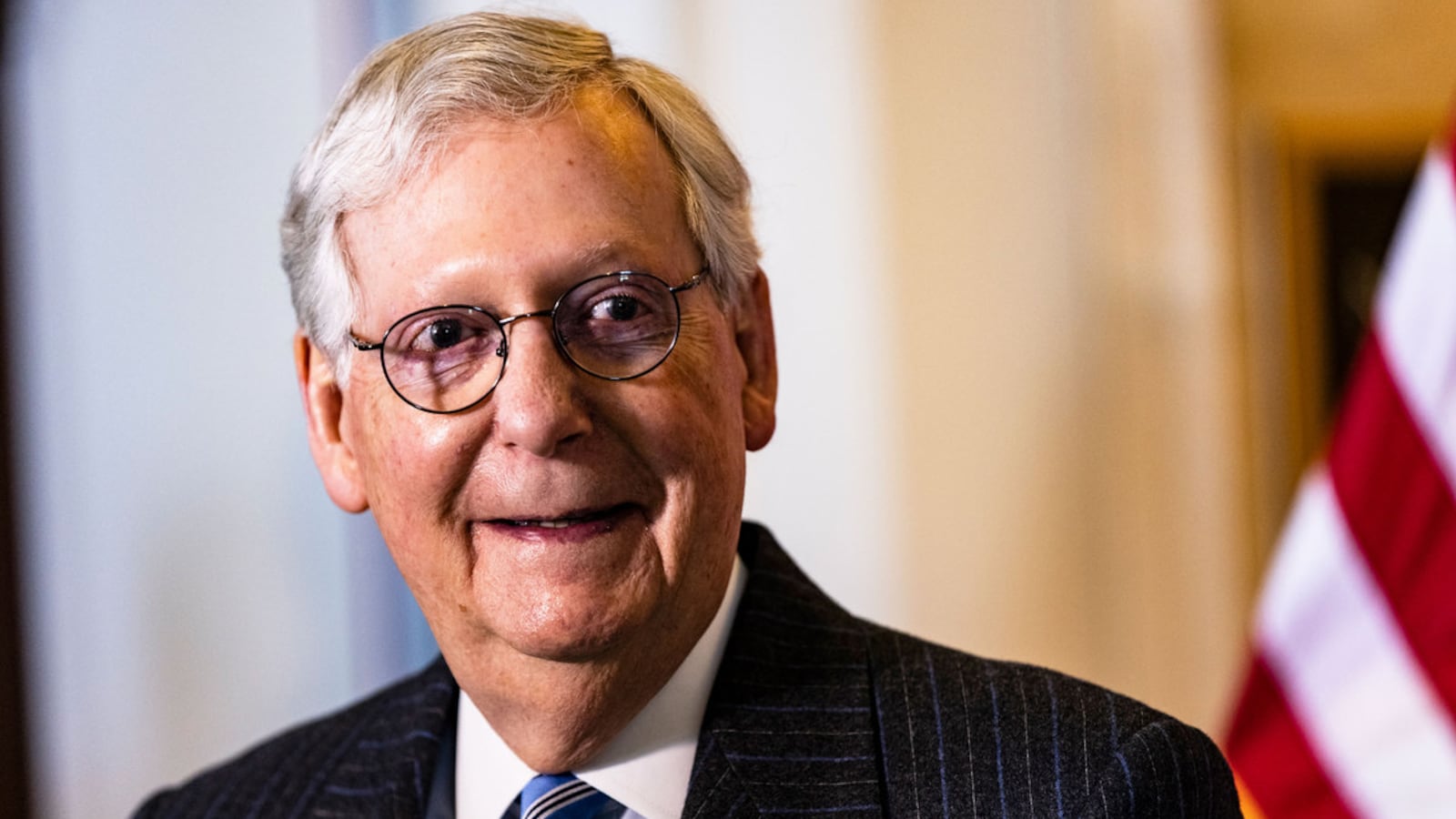

It turns out that Mitch McConnell doesn’t actually think corporations are people or that money is speech if the companies in question aren’t speaking his language. Instead, he warned them to “stay out of politics,” since they “invite serious consequences if they become a vehicle for far-left mobs.” Uh huh.

Mitch, who then tried to step away from his remarks since "I didn't say that artfully," is mad because large employers in Georgia eventually got around to responding to a voter suppression law there that may as well have been authored by Lester Maddox. The companies came out for the controversial proposition, in GOP circles, that every American should have the right and opportunity to vote.

And that isn't what McConnell signed up for as he spent the past three decades waging war on behalf of unregulated corporate cash’s "right" to corrupt our democracy. What he meant, as anyone who's watched his incredibly destructive career knows, is that those corporations were welcome to bestow wheelbarrows of cash upon Republicans, to relieve him of the burden of having to actually develop policy ideas to improve Americans' lives and get around the fact he's a charisma event horizon.

That money also helps him buy off Senate Republicans, who just happen to be the electorate for Republican leader. It’s allowed McConnell to have a Senate career one might consider a tribute to Seinfeld, in that it's been about absolutely nothing. Except power. As long as corporations paid up and shared opinions he liked—low taxation, deregulation, free trade—Mitch was more of a "speak up, fair CEO's" kinda guy. The problem is that as our culture began to change, corporations did too.

Some companies were suddenly helmed by leaders who believe in such crazy concepts as LGBTQ rights, equal pay and racial equality. Or at least knew to publicly support these precepts to appeal to their customer bases. On those issues, as far as McConnell's concerned, you can spend the night, but just leave your check on the nightstand before heading home. No talking.

To be fair, McConnell’s been principled in that position—that corporate donations are good only insofar as they’re good for McConnell—for as long as he’s been in politics, as Alec MacGillis details in The Cynic: The Political Education of Mitch McConnell. In 1973, McConnell published an op-ed favoring partially publicly financing campaigns and setting limits on spending.

By 1987, Senator McConnell "sponsored a proposed constitutional amendment giving Congress the power to limit independent expenditures on campaigns and on candidates' use of personal funds for their own races." (McConnell, at that time, was far from wealthy).

By 1990, he was pushing to ban political action committees. This just happened to be at a time when Democrats had had ironclad control of the U.S. House of Representatives for nearly four decades, so PACS gave more to Democrats than Republicans. It happened to McConnell in his first Senate race in 1984. The incumbent Democrat he ousted, Walter "Dee" Huddleston, was favored by PACS, to the chagrin of McConnell.

But that would change once Mitch mastered the art of the shakedown. He came to oppose all campaign finance reform, challenging FEC rulings and filing amicus briefs challenging any contribution limits that might end up in front of the Supreme Court. In this way, he was a driving force behind Citizens United.

Yet, if you think this carried over to his thinking on actual corporate speech, the kind that exits from the mouth and not the wallet, think again. From a piece I wrote back in 2004 on then-Senate Whip McConnell:

McConnell also knows how to use threats. When a group of Republican senators signed onto a campaign-finance reform measure in the late ‘90s, McConnell, in his position as NRSC chair, advised them that they could expect no electoral support from the committee unless they switched their position. At least one, Sen. Sam Brownback (R-Kan.) did so after receiving McConnell’s warning. Then in 1999, when the Committee for Economic Development (CED)—a trade group representing large corporations—announced its support for a ban on soft money, McConnell wrote a furious letter, on NRSC letterhead, to leaders of companies belonging to CED, denouncing the group’s “all-out campaign to eviscerate private-sector participation in politics,” and urging them to quit the organization. “I hope you will resign from CED,” he scribbled at the bottom of one copy. Many recipients of the letter saw in it an implicit threat that, unless they withdrew from CED and stopped supporting reform efforts, their companies would receive unfavorable treatment from Congress.

Which brings us back to McConnell's supposed support for money in politics based on the First Amendment or some other such principle. This isn’t that. McConnell has no issue with the MyPillow guy ranting about a coup or the Goya CEO supporting sedition. But he has a big issue with corporate actors speaking out in favor of voting rights. Because, as 2020 showed, McConnell's party is mostly talking to the Fox News "I've Fallen And I Can't Get Up" demographic, not those who reject an America of transgender bans, stand your ground, and testifying fetuses.

Companies that create things need an educated workforce, which increasingly means Democratic and socially tolerant. And they must appeal to consumers with disposable income who actually buy stuff. Needless to say, these folks tend not to reside in what you'd call "the Hannity demographic."

So Mitch doesn’t want these companies to talk. But as Georgia has proven, they're going to anyhow, because the alternative is alienating their customers, and no amount of crazy GOP tweets suggesting major league baseball is is an offshoot of the “China Virus” that makes its players do double headers reading Dr. Seuss will change that fact.

What this all means is that Mitch is finally reaping the whirlwind of the corporate speech he was so keen to unleash on our politics back when it benefitted him and his party.