Sometimes aspects of life become so royally fucked up, there comes a point when you say, “Eh, screw it, I’ll go along with this for a bit, let’s kick it up to another level.”

This country loves the Fourth of July—maybe less at present from the standpoint of proud patriotism, especially with how we’ve been going for a few years now, but certainly because of good times with friends, beers, cookouts, laughs, camaraderie, in-person summer social manna, which for many people is quite different than a chat on the phone.

The Twilight Zone has a marathon every year, which is apt for our age, but given the level of absurdity that has become our prevailing planar field, the most bonkers Fourth of July special of all-time may be the most fitting for this bonkers Fourth of July of self-isolating and wondering just what the hell to do with yourself.

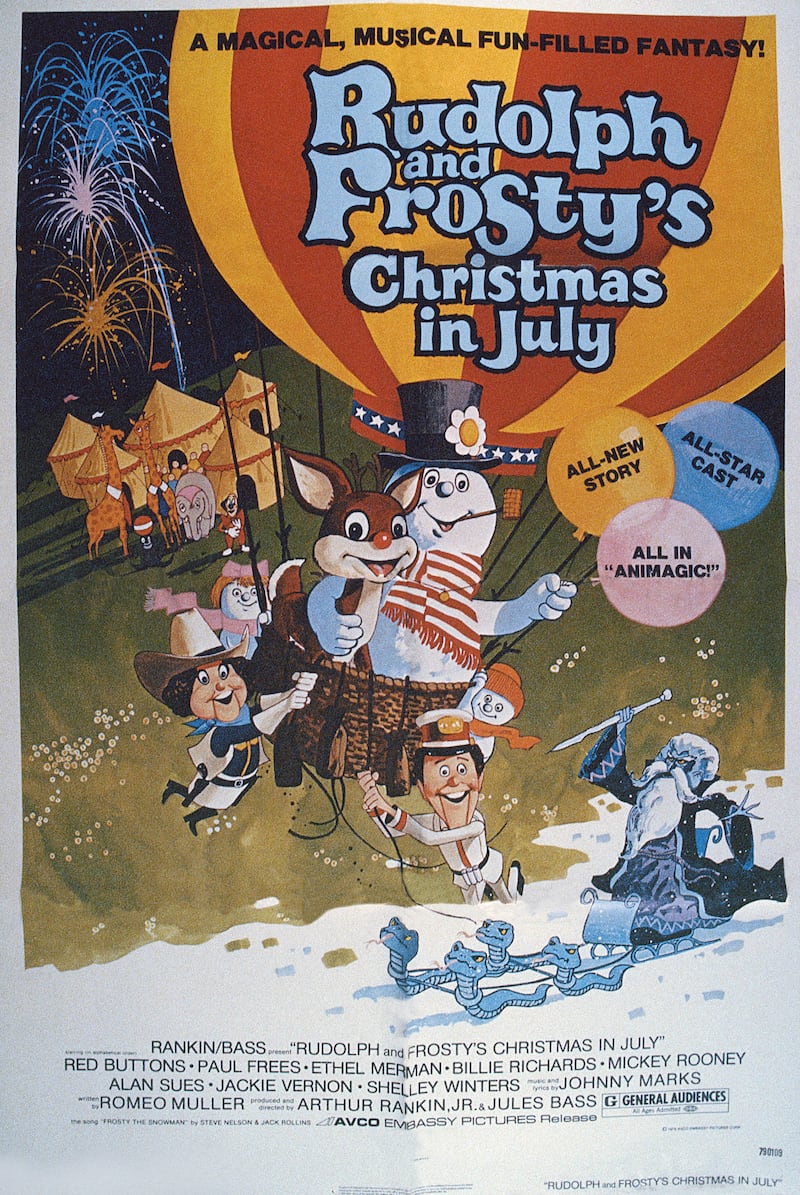

There’s no faulting anyone who says, “Stop trying to make Christmas in July a thing.” The idea is one that has never caught on, though bars would try mid-summer Christmas-related promotions, back when we could go to bars, and some network is always firing up a roster of Christmas movie fare. The people at the Rankin/Bass production company went one better back in the day, when they had an idea to take their iconic version of Rudolph, pair him with Frosty the Snowman and the bulbous dude’s family, and pack them off on a Fourth of July holiday.

Everyone knows the original Rudolph special from 1964, but what you might not know was that Rankin/Bass kept at their trade for some time after, getting weirder and weirder, druggier and druggier. If you were going to day drink and get smashed on the Fourth, you would fit the bill for the demo of 1979’s Rudolph and Frosty's Christmas in July.

But what’s more bizarre yet—not to suggest that Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass were masters of prognostication—is that this hour-and-a-half long film actually dovetails with our cancel culture, because it is the shiny-beaked fellow for whom the mob comes. People say the mob eat their own? Well, get prepared to watch characters who are otherwise meant to be cute and lovable get their knives out for the reindeer whose life, future prospects, and employability, must be stamped out like a soft grape under a hard hoof.

We begin with Rudolph chilling with Frosty and his two kids, who want the reindeer to show off his nose, which Rudolph finds irritating, but fine, whatever, here you go, kids. Problem is, the bulb flickers, out it goes, our hero has been compromised. There’s this tang of impotence in front of the children, which is discomfiting, but we are just getting started on the bizarre front.

Frosty first appeared in cartoon form in the Rankin/Bass world in 1969, but here he gets what they called their Animagic treatment. You probably term it Claymation, but you know the deal. We’re treated to a montage backstory of Rudolph’s heroic origins. James Joyce could appear less interested in intertextuality than the Rankin/Bass team, which is kind of admirable.

In the montage, you see Clarice—in new animation—who had been Rudolph’s lady love back in 1964, the bumbling elves from the still-quite-terrifying The Year Without a Santa Claus (that’s the one with the Miser Brothers), but now we get this bonus scene. Turns out that when Rudolph was born, his mom left him alone for a bit in their reindeer cave (WTF?) to go find her husband, who, if you might recall from the original, shamed his son when he was not yet five minutes old, and was a total jerk, as was Santa.

Rudolph is alone, and Lady Boreal, a nature deity made of a beam of light (usually) and human form (sometimes), turns up, carves this strange mark on Rudolph’s hoof, and now he is the magic carrier of the light—i.e., he has a bright nose—so long as he doesn’t pull some dickish move. Pull the dickish move, lose the light forever.

But here’s the problem: a winter wizard (there are a bunch of these in Rankin-Bass-dom) named Winterbolt wants to kill off Santa, wreck Rudolph, and be the main Christmas honcho. His opportunity comes when Frosty and Rudolph decide to take a Fourth of July vacation together to a carnival far off in a hot spot by the sea, because kids, as we are told, should see the circus at least once before they die. (Who the hell talks like this?)

There’s no way to walk you through everything that happens next and still sound like a reasonable human. Winterbolt has pet dragons with freaky, snake-like constructions coming out of their mouths. Winterbolt himself has these magic amulets that he gives to Frosty and his crew so that they won’t melt on their vacation (spoiler: it’s a lie). There’s a dude who is in love with one of the carny folk, an ice cream man who hawks his wares from a hot-air balloon. But there’s also a Karen, albeit a male Karen who also seems dogged by some condition you are seemingly supposed to believe is STD-adjacent.

This would be the reindeer Scratcher (a little on the nose, yes?), who is envious of Rudolph. Winterbolt busts him out of the clink, presses him into his employ, and Scratcher—who looks like an animated advertisement for hand sanitizer—ends up framing Rudolph, who, we should add, has started working for the circus. He’s a treasurer, maybe? The nefarious Scratcher takes a job as a roustabout, a word that no child on earth knows, to abet with the set-up to frame Rudolph. Frosty is the only character who understands the reasons why Rudolph can’t explain that he’s innocent. This has to do with a promise, saving Frosty’s life, it doesn’t really matter.

Everyone quickly goes from “you’re the best, my guy,” to “you suck, you evil monster,” and Rudolph doesn’t seem to want to say anything. He’s broken. Rudolph can apologize for something he didn’t do, and he does, after a fashion, but that’s not especially pertinent or useful, just like the apologies we often see people make today. Do they believe their own expression of contrition? Do we care? Do we care about our own culpability if we’ve made someone else feel like they must beg our forgiveness, as though they answer to us, and all they did was hold a viewpoint that we can’t reconcile with ours?

Then there’s Frosty, who is going to let Rudolph take this hit. He looks at it as preservation of his family. That’s his focus, more so than community, or this ancient thing we used to have that Kant called the categorical imperative, which you and I call doing the right thing. The songstresses of the carnival specialize in country and western music with a blues tinge, so there’s also this Hank Williams vibe. The police and guns playing a pivotal role before natural order is restored, though I’m not sure how natural that can ever be again, after all of this. Rudolph could well have been thinking, “Welcome to the new normal, baby, God help us,” for all we know.

One might imagine Rankin and Bass making this as this kind of dare-based drinking game, where each of them would come up with a crazy idea, to have the other try and top it. Consider, for instance, when Rudolph, accused by all, shamed, his career in tatters, his nose utterly useless, takes what appears to be a walk to the coast to end it all.

Did you ever see Rudolph’s Shiny New Year? That was another Rankin/Bass special from 1976, which was trippy but not this trippy. It featured Big Ben, a whale with a clock embedded in its flesh, as if in a blended homage to Proust and Dalí. And lo, up he comes swimming now, to intervene just in time, though he leaves straight away, because he has to get to South America. Of course. Tons of sense.

It gets even stranger at the end when, in need of a snow squall as Frosty and his family die right in front of us, a simple invocation makes Jack Frost appear. Ta-da. Problem solved, snow people resurrected. Or hardened. Packed. Call it what you will.

It’s hard to think of a better Fourth of July special to get high or drunk to, or to just watch for a harmless diversion, the embracing of a benign form of absurdity in a world right now that is shot through with a decidedly baneful form of absurdity. You can take it as you want it, which is what Rankin and Bass probably had in mind.

But it is true, you should see a carnival before you die.