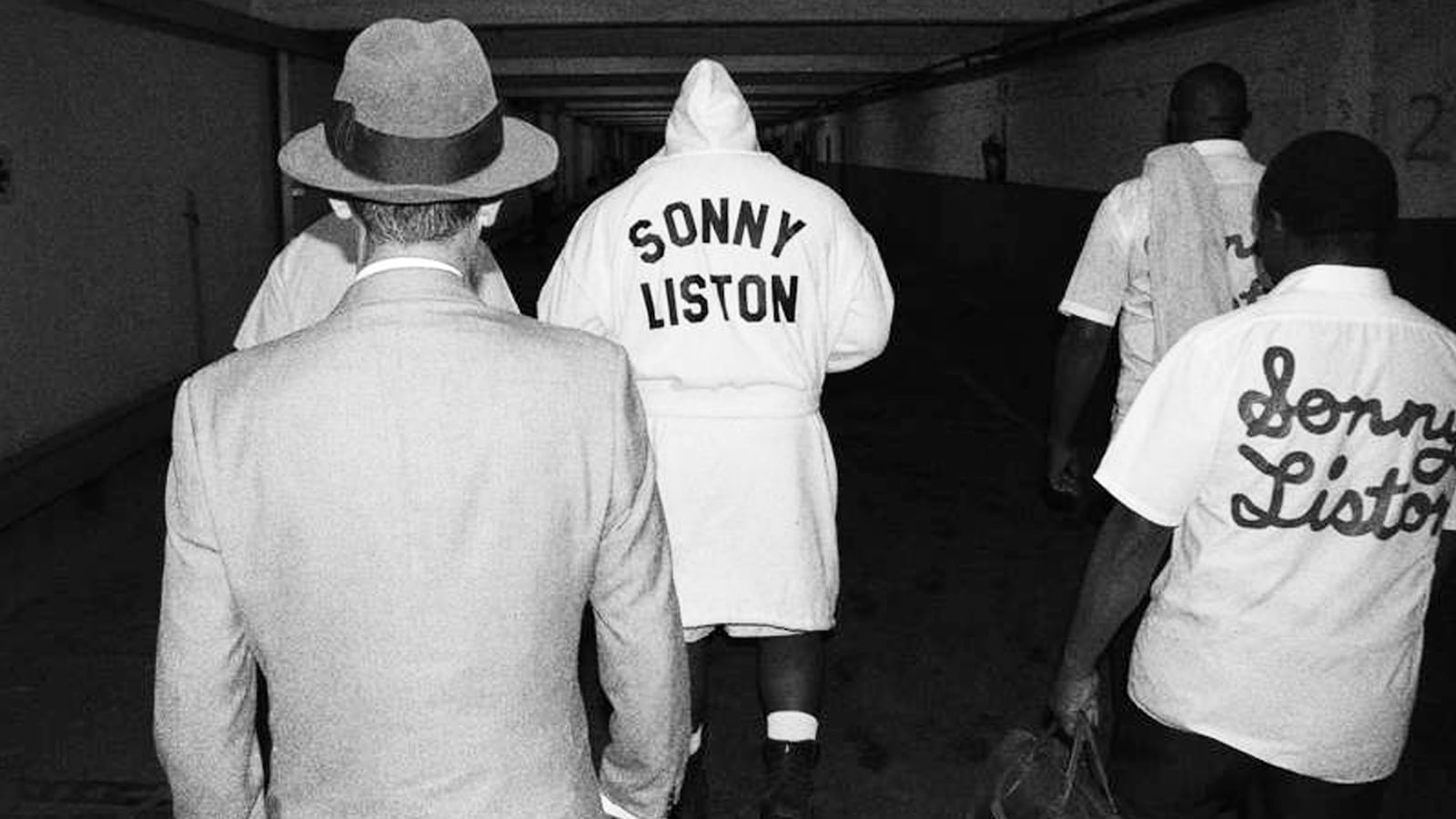

There was arguably no more intimidating fighter in boxing history than Sonny Liston. Yet as elucidated by Pariah: The Lives and Deaths of Sonny Liston, that may be the only definitive thing one can say about the former heavyweight champion, who despite his celebrity lived much of his life in the shadows—which is where he also died, alone, in 1970, the victim of any number of possible enemies.

Developed from Shaun Assael’s The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin, and Heavyweights, writer/director Simon George’s documentary (premiering Nov. 15 on Showtime) is a riveting account of the athlete’s rise and fall, both of which were stained by criminality and marked by questions without concrete answers. What was incontrovertibly true about the fearsome pugilist is that, at his peak, he was a freight train in the ring, steamrolling opponents with unmatched power and ferocity. So brutal was Liston that his jab—normally a punch used to set up more powerful blows—was downright lethal, described by Purdue University history professor Randy Roberts as “like getting hit by a pole.”

Even Mike Tyson, himself no stranger to scaring adversaries silly, says, “Sonny Liston had a big, menacing tough-guy reputation, and that superseded him in the ring. He intimidates the fighter. The fighter’s really beaten before he even got in the ring.”

Liston’s formidable persona was crafted at an early age, thanks to a sharecropper father who used to hook his son up to a harness and have him pull a plow through the fields like a mule. Such demeaning treatment, along with daily whippings, no doubt took their toll on the young Liston’s psyche, and when his mother left their Arkansas home (and her 25 children) for a better life in St. Louis, Liston followed—only to fall into a life of petty crime, which ultimately led to a five-year prison stint for armed robbery in 1950. It was there, in Missouri State Penitentiary, that Father Alois Stevens convinced Liston to join the boxing program. Before long, he was bludgeoning anyone who dared face him, be they inmates or aspiring heavyweights brought in to spar.

The manager of one of those fighters, Frank Mitchell, took a shine to Liston. Mitchell was also in good with Frankie Carbo, an underworld bigwig who ran American professional boxing, and thus began Liston’s lifelong relationship with the mob. With their backing, he won two amateur Golden Gloves tournaments and then moved on to the professional ranks, where his “seek and destroy” mentality heralded the future of the sport. Although he only weighed in at 6 feet tall and 200 pounds, Liston was a veritable tank of a man, his long reach and enormous hands allowing him to dish out a degree of punishing damage never seen before.

He was, in a word, terrifying. That status was only enhanced by his connections to organized crime, which along with his arrest record, including nine months behind bars for a 1956 incident in which he took away a cop’s gun and beat him silly in an alley—made him the personification of the big, bad, scary black man stereotype. No matter his marriage to sweet and loyal wife Geraldine, as well as claims that he was a “sensitive” soul in private—by the time Liston was ready for a title fight against reigning champ Floyd Patterson in 1960, he was viewed by most as “America’s worst nightmare.” And following Patterson’s failed attempts to duck their bout (over Liston’s mob connections), Liston snatched the belt away from the champ in decisive fashion in 1962.

That triumph, however, didn’t help Liston defeat the perception that he was an abominable monster. As illuminatingly conveyed by Pariah through a combination of new interviews, archival footage, Liston quotes, and dramatic recreations, racist white America saw Liston as an uncontrollable, raging black brute. Black America, meanwhile, viewed him as the antithesis of the sort of model African-American needed by the Civil Rights Movement (an image that the roundly defeated Patterson fit). When Liston discovered that being champion wouldn’t gain him the mainstream respect he craved, he fell in further with the mob—only briefly getting the public on his side when he went toe-to-toe against loudmouth challenger Cassius Clay, whom white fans detested even more than Liston because of his affiliation with the Nation of Islam.

It’s this portion of Liston’s life that Pariah mines most fruitfully, exploring the confluence of personal and cultural forces that thrust the boxer into a maelstrom for which he was unprepared. Director George captures the way in which Liston became a lightning-rod racial symbol at multiple points during his career—due to a combination of his own choices and mistakes, and the circumstances of his life. Moreover, the film gets mileage out of the mysterious twists and turns that befell Liston after he lost his title on Feb. 25, 1964, to Clay, in a bout that found Liston refusing to get up off his stool to begin the seventh round. That strange situation convinced many that the fix was in, and those cries grew even louder when he went down early (in dubious manner) during their May 25, 1965, rematch—a loss that spawned the “secret percentage theory,” which hypothesized that Liston took a dive in return for a cut of Ali’s future earnings.

Just as beguiling was Liston’s demise, which came after he relocated to Vegas, fell in with mobster Ash Resnick, and began working as a leg-breaking enforcer and drug dealer on the city’s seedy Westside. On January 5, 1971, Liston was found dead and decomposing by Geraldine in their home, a week or so after he’d apparently passed away from a supposed heroin overdose. Pariah’s many talking heads posit a variety of potential explanations for what did Liston in, including that he was executed as payback for ratting out a fellow dealer, and that he was offed by the mob for failing to throw his July 29, 1970, bout with Chuck Wepner. The coroner’s conclusion that he died of “natural causes” only fueled speculation, which Pariah digs into in tantalizing detail.

Neither condemning nor celebrating Liston for the misfortunes he suffered, Pariah instead proves a melancholy tale about an all-time great burdened by sins of his own making and prejudices and predicaments out of his control. It’s a saga about people’s inability to escape the past—as well as the reputations that, whether fair or unfair, come to define us.