Days after Brooklyn rapper Bashar Barakah Jackson, better known as Pop Smoke, was killed during a home invasion in Los Angeles, authorities are still investigating the motives behind the attack. Thursday night, TMZ reported that the tragedy appeared to be a “targeted hit... not a robbery.” But on Friday afternoon, LAPD Capt. Jonathan Tippet, head of the Robbery-Homicide Division, disputed their assessment in a phone call with The Daily Beast. “That was not entirely accurate,” Capt. Tippet said.

The invasion occurred early Wednesday morning, while the rapper behind 2019 hit “Welcome to the Party” was staying at a rental home in the Hollywood Hills. At 4:29 a.m., the Los Angeles Police Department received a radio call about an “assault with deadly weapon” involving a then-unknown number of suspects at a home on Hercules Drive. When law enforcement arrived, they found Jackson gravely wounded and transported him to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Mid-City West. He died from his injuries 45 minutes later. Friday morning, the Los Angeles County Coroner’s officer declared the death a homicide by gunshot wound to the torso. The rapper was just 20 years old.

Jackson had been staying in a cream-colored home owned by Edwin Arroyave and Real Housewives of Beverly Hills star Teddi Mellencamp, according to property records, in the kind of affluent neighborhood where every home is outfitted with security cameras or dystopian video doorbells. As part of the investigation, Los Angeles police collected footage from cameras at several houses down the block, though Capt. Tippet declined to say how many. From several videos, which Tippet described in limited detail, it is possible to make out four individuals wearing masks and sweatshirts approaching and leaving the residence. “We’re following a lot of evidence and video and putting all of that together,” Capt. Tippet said. “Throughout the neighborhood there’s different videos and there was video at the residence as well. [We] don’t know what time they entered the residence.”

In TMZ’s report, sources who had watched the surveillance footage described what they had seen. In the tape, four men approached the house and walked around the back. A few minutes later, TMZ’s sources said, three returned to the front of the home. The fourth seemingly entered through the backdoor, which had no cameras trained on it. In that time, multiple shots were fired, striking only Jackson. Minutes later, according to TMZ, the fourth individual walked out the front door of the house, apparently empty-handed. “Here’s the thing,” TMZ concluded, “the folks who have seen the surveillance video tell us the person inside the house—presumably the shooter—did not carry anything out. Given that he shot someone, it’s doubtful he would take the time to stuff items in his pocket.”

Capt. Tippet refuted their interpretation of the footage. “That is not entirely true,” he said. “Some of the individuals were not holding anything after leaving the residence. But it is not true to say that nothing was taken. That’s not entirely accurate... We have some indication of what was taken, but I can’t confirm any details about that... There’s no sense of whether it was a robbery effort or a targeted effort.”

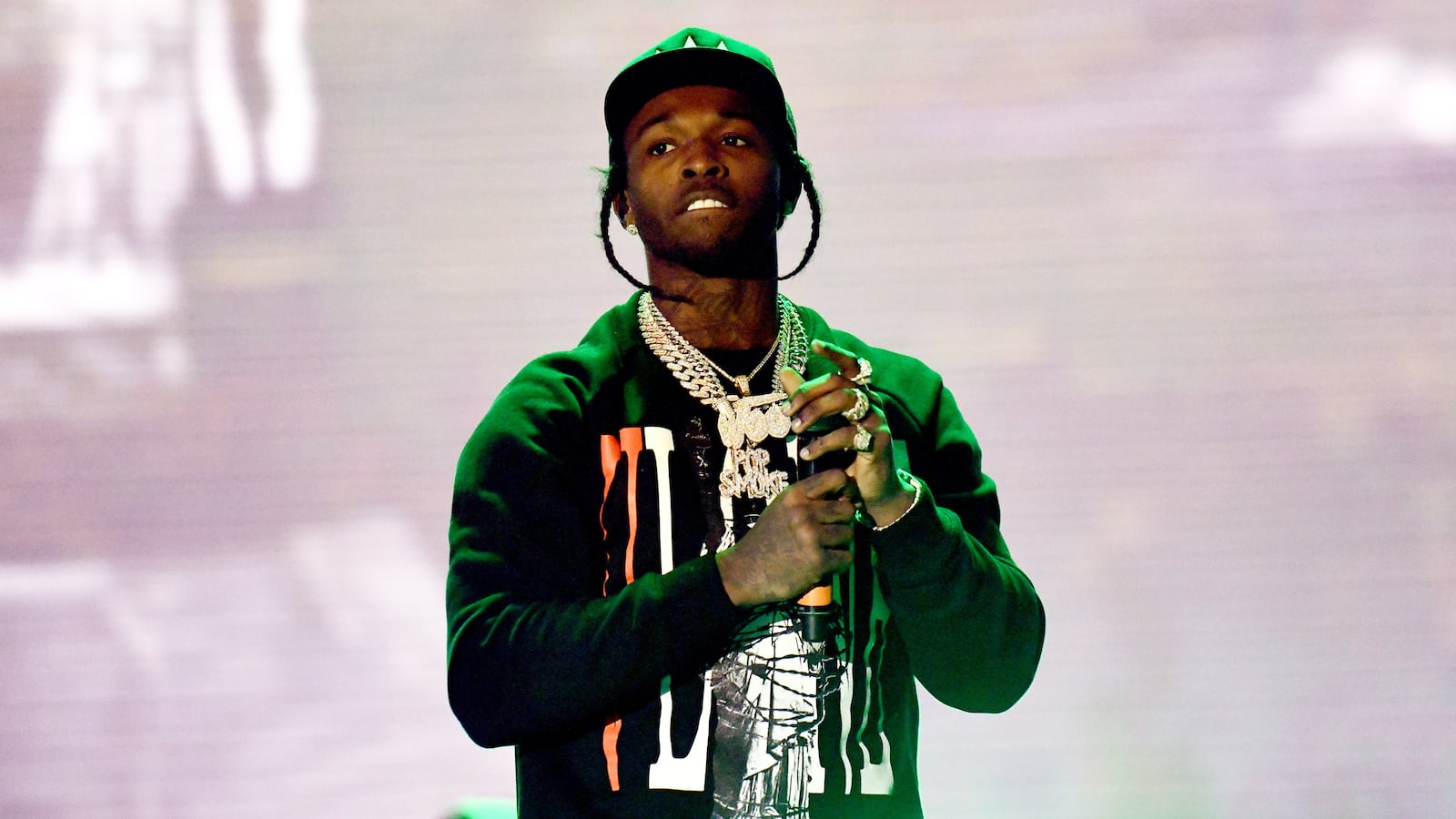

Jackson rose to national fame last summer when his single, “Welcome to the Party,” made him a breakout star of the Brooklyn drill scene. Drill, the gritty, hard-trap hybrid, emerged from Chicago in the 2010s, got imported to the U.K., and rebounded to New York. The three scenes are discrete but interrelated, illustrated in Jackson’s coming-up story. Born to Jamaican and Panamanian parents, Jackson grew up in Canarsie, the South Brooklyn neighborhood. He played basketball (he was awarded a scholarship to a Philadelphia prep school at age 15); obsessed over nice cars (he told The New York Times he bought a BMW 5 Series at age 16); and tinkered with music, often playing drums in church.

In December of 2018, when Jackson first started recording his own stuff, he got lost in YouTube’s algorithm and stumbled on a beat from an East London producer named 808 Melo (now 808MeloBeats). Jackson bought the track, befriended the producer, and eventually flew him to the States to collaborate. It was over a U.K. beat that the kid from Canarsie wrote “Welcome to the Party” in one mad half-hour stint, launching the hit that became inescapable last summer.

When the track debuted on YouTube last May, “Welcome to the Party” racked up views by the millions (current count: 27 million), prompting remixes from Nicki Minaj, A$AP Ferg, Pusha T, and Rico Nasty. The beat was gloomy and fast-paced; Jackson’s vocals were gravelly and cartoon-villain deep—so much so they became a kind of incredulous punchline. “His voice sound like he gave cigarettes cancer,” one YouTube user wrote. A standout single on his 2019 debut mixtape, Meet the Woo, the track established Pop Smoke as a star of the often insular Brooklyn drill scene and a known quantity to audiences well outside it.

If Jackson was not yet a household name when he died, he spent the past year paving his way there. He signed to Victor Victor Worldwide, an offshoot of Republic Records at Universal Music Group. He collaborated with rappers like Lil Tjay and Travis Scott. He toured the U.K. with Skepta; announced an upcoming movie role in Eddie Huang’s film Boogie; and attended Virgil Abloh’s Off-White show during Paris Fashion Week.

There were some bumps along the way. Last fall, Jackson was pulled from the line-up at New York Rolling Loud alongside four other rappers over NYPD concerns that the performers had been “associated with recent acts of violence citywide,” according to a letter from NYPD Assistant Chief Martin Morales. And last month, Jackson was arrested on his way back from Paris Fashion Week at JFK Airport in New York on accusations of stealing a $375,000 Rolls Royce for a music video.

News of Jackson’s death triggered an outpouring of grief from fans and music industry peers. Just days before his death, the Brooklyn rapper had released his second mixtape, Meet the Woo 2, which debuted at No. 7 on the Billboard album chart. In their mourning, some fans and armchair detectives speculated that the perpetrators had intended to rob the rapper. Earlier that day, Pop Smoke had uploaded photos on Instagram of him sitting in a luxe car, with a friend holding wads of cash. He had also shared an Instagram story where the Hollywood Hills address was visible on a designer label. Jackson's friend, Michael Durodola, who goes by Mike Dee, vigorously denied any allegations of a set-up on Instagram. “I just lost my f***ing brother, my heart my dawgz,” he wrote in a caption. “You guys have no type of sense or sympathy!”

But most reactions were heartbroken over what Jackson’s absence meant for music. “The Bible tells us that jealousy is as cruel as the grave,” Nicki Minaj wrote on Instagram. “Unbelievable. Rest In Peace, Pop.” The range of talent grieving his death—from Chance the Rapper to ?uestlove to Kehlani to Nas—spoke to the rapper’s wide appeal, which he’d described in Vice’s i-D last year: “I think everybody should listen to Pop Smoke,” he said. “From your 9-5 regular person to your super rich stockbroker, from your drug dealer to your athlete. Maybe your teacher! Anyone can listen to Pop!”

For two days after his death, the street where Jackson died was taped off and crowded with police, news trucks, rubberneckers, and fans. But Friday afternoon, Hercules Drive was all but empty. Down the road, two construction workers painted a nearby house. A man tinkered over his convertible. “It was impossible for a few days,” said one neighbor wearing bright-red lipstick and a bathrobe from her front door. “But now it seems weirdly normal.”

The $2.5 million house where Jackson had been staying was vacant except for a housekeeper. She hadn’t heard much about what had happened, she said, declining to give her name. He had been there just two days. As she spoke, three young girls drove up and approached the house, taking pictures of the small shrine where visitors had left three lit candles, a small bouquet of flowers, and a crumpled dollar bill. “We love him,” one of the girls said, likewise withholding her name. “We only heard about him when he died, from the internet.”