This is part of our weekly series, Lost Masterpieces, about the greatest buildings and works of art that were destroyed or never completed.

It was the commission of a lifetime—an invitation from the president himself to visit his vacation home for a long weekend to paint a life-sized portrait that would be displayed for all to see. It wasn’t the first time Elizabeth Shoumatoff had raised her brush to capture the likeness of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but it would be the most prestigious.

Little did the publicity-shy artist know that this commission would never be completed and would ultimately place her in the spotlight of history.

Shoumatoff may not be a household name today—a result more of personal preference than the vagaries of historical memory—but, in the first half of the 19th century, she painted portraits for clients with names like Frick, du Pont, Woodruff, and Mellon.

She lived the American dream, arriving in the country a political refugee and dying at the age of 92 having become a presidential portraitist and chronicler of America’s most prominent families.

Born in 1888 in Russia, Shoumatoff grew up the daughter of a family that was well-to-do enough to spend summers in the Ukrainian countryside and winters in St. Petersburg. Early on, it became clear that she was a natural born artist.

An early governess taught her watercolor, but, beyond that instruction, she had little formal training in art. But she did have a dream. From a young age, Shoumatoff says she wanted to be a new Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, “paint[ing] portraits of famous people.”

But in 1917, when Shoumatoff was 19 and already married with a child, Russia was turned upside down by revolution. Her family left the country, taking a harried train ride through Siberia to the Pacific Ocean. By the time they reached the U.S., a second Communist revolution had overthrown the provisional government and one of her brothers had been arrested, never to be heard from again.

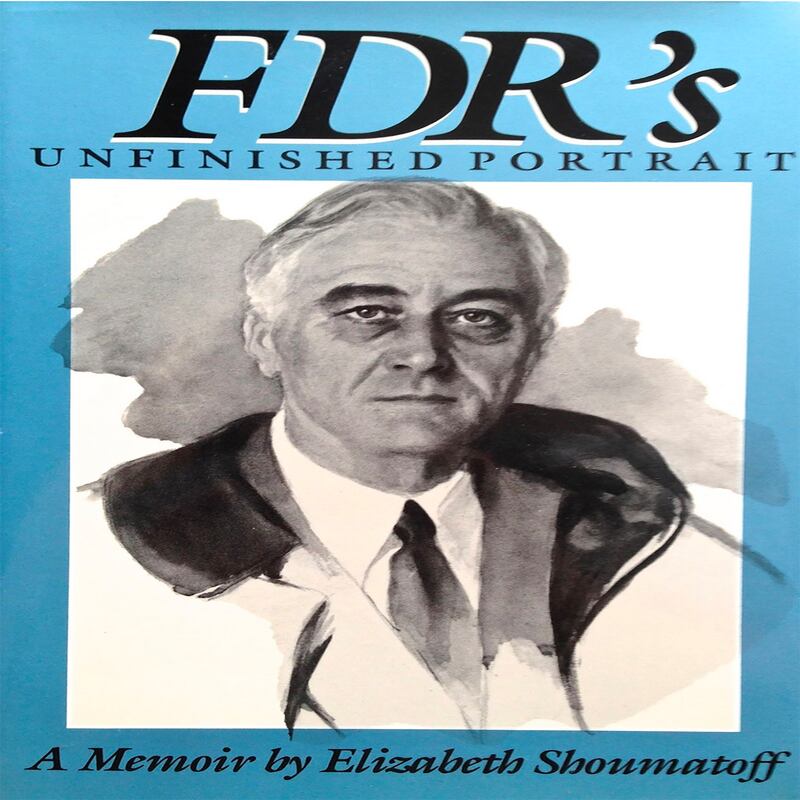

“I cannot tell how distressed I was at the thought of living in America, which at that time meant only skyscrapers, dollars, and gangsters to me,” Shoumatoff writes in her autobiography FDR’s Unfinished Portrait: A Memoir. How little did she know that one day she would be one of the few present at a key moment in the country’s history.

Once in the U.S., the family settled first in Upstate New York, then moved to Long Island where her husband became an executive at an aeronautics company. Shoumatoff resumed painting—taking commissions for watercolor portraits—and had two more children.

But in 1928, her life changed again when her husband died in a tragic accident while swimming. Painting now was more than a pastime; she had to support her family through her art.

From 1917 to 1980, Shoumatoff would paint over 2,000 portraits. For some of her biggest clients, like the Frick’s, she ultimately recorded several generations of family members and several branches of the family.

“What a life! What a wonderful life it was! To have had the opportunity to paint so many interesting people, some quite extraordinary, others just delightful and often amusing; to know them so well and later to enjoy their friendship. What could be more exciting and gratifying?” Shoumatoff writes in her memoir.

It was one of these subjects, Lucy Rutherfurd, who would play the key role in introducing Shoumatoff to the president.

Before FDR became the 32nd U.S. president, he had an affair with Rutherfurd. While they ultimately broke it off (although not necessarily forever), they remained close friends until his very last day. Rutherfurd was delighted by the portrait Shoumatoff painted of her, and spread the word to the Oval Office that Roosevelt should hire the artist to make one of his own.

So, in 1943, Shoumatoff found herself at the gates of the White House, drafting board, pencil, and watercolors in hand. Over the course of three days, she painted a small, 10-by-12 inch portrait of the president.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of Shoumatoff’s memoir is her recollection of their conversations during these sittings.

In 1943, the president was particularly harried by the various members of European royalty who had sought refuge in the United States. It seems, once settled in their temporary home, they expected their host, who was rapidly losing patience with the royal freeloaders, to take care of them and treat them with all the pomp and circumstance that they were accustomed to in their own countries.

Shoumatoff remembers Roosevelt telling her that Queen Charlotte of Luxembourg wrote him letters complaining “about the fact that there is not enough fuss made over her presence here,” the Norwegians were very formal and “very pompous,” and the Queen of Holland “had no sense of humor and kept getting offended” by things that were said and done.

Roosevelt admitted, with implied humor, that “he had created the problem himself, [and] he did not know what to do about it.”

Overall, the session was a huge success on both sides. Previously, the conservative Shoumatoff had not been a fan of the president, but she left the White House utterly charmed. The president, for his part, loved the small portrait so much that he asked Shoumatoff to paint a second, life-sized portrait to hang in the White House or his vacation home, the Little White House, in Warm Springs, GA.

The war intervened, so it wasn’t until April 1945 that the president sent Shoumatoff an invitation to join him in Warm Springs to undertake the commission.

Shoumatoff remembers being shocked by Roosevelt’s clear decline in health. They staged the sitting so that she would paint him outdoors (not a backdrop she was accustomed to), with his cape draped about his shoulders and a scroll in his hand to symbolize the United Nations Charter that he was supposed to sign in San Francisco a few weeks later.

On the fourth morning of the sitting, Shoumatoff remembers him looking much better and being in a better mood than he had up to that point.

“As I started mixing my paint, I looked very carefully at his face. I was struck by his exceptionally good color. That gray look had disappeared. (I was told later by doctors that this was caused by the approaching cerebral hemorrhate [sic].)”

His final words were to the butler, who had come in to set the table for lunch. “We have fifteen more minutes to work,” he told him, as he continued posing for Shoumatoff. Shortly afterward, he silently slumped forward in his chair. Shoumatoff ran out to the garden to alert the Secret Service. Her last image of the president was one befitting an artist.

“Entering the hall I had my last glance of President Roosevelt, being carried to his room. I could not see exactly who was carrying him but I will never forget that silhouette on the background of the open door to the sunny porch.”

The following days were Shoumatoff’s worst nightmare. For years, she had avoided publicity like the plague, one of the reasons her rich clients liked and trusted her. But, as one of only three people in the room when the president lost consciousness, the swarm of journalists, government officials, and biographers quickly descended. So, too, did the conspiracy theorists who jumped on the fact that Roosevelt died “having his portrait painted by a generally unheard of artist, Russian besides.”

Shoumatoff’s son Nicholas recalls that, for years afterwards, his mother refused to paint any heads of state. But she got over her fear, and went on to continue her storied career, eventually adding LBJ and Lady Bird Johnson to her roster of impressive clients.

As for the very last portrait of FDR, the painting remained unfinished (because of the outdoor setting Shoumatoff could only complete it from life).

It was stored for years in a warehouse in New York until the commission at Warm Springs approached the artist, asking her to donate it to the museum they were creating in Roosevelt’s country home.

Today, the portrait hangs on a wall at the Little White House where FDR died, the president looking distinguished and pensive as his head and shoulders disappear into a swath of blank canvas.