In 1988, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin debuted an exhibition of Lucian Freud paintings. By all accounts, the show was a success, with the Germans warmly embracing the work of the famed British painter…maybe a little too warmly.

On May 27, the gallery filled with students on a trip to see the exhibit. It was just another day at the show with visitors milling around examining Freud’s paintings under the watchful eye of art guards when someone noticed something alarming—one of the works was missing.

In broad daylight, in the middle of a crowded show, someone had absconded with Lucian Freud’s relatively small painting of his one-time friend Francis Bacon.

The painting in question was a 7-by-5-inch oil painting on a sheet of copper that had been completed in 1952, the same year the Tate in London acquired it for their permanent collection.

While Freud had started a second painting of his fellow artist, the missing copper canvas was the only portrait of Bacon that he ever completed.

In a 2008 piece in The Guardian, art critic Robert Hughes called the painting an “unequivocal masterpiece,” continuing on to write “that smooth, pallid pear of a face like a hand-grenade on the point of detonation, those evasive-looking eyes under their blade-like lids, had long struck me as one of the key images of modernity.”

But twenty years earlier, that important “image of modernity” had disappeared with not so much as a peep heard or a glimpse caught in the time since. Zero substantial leads have turned up in the case of the missing Francis Bacon.

The seeds of Freud’s small masterpiece were sown in 1945, when Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon were introduced by their mutual friend, artist Graham Sutherland.

The 23-year-old Freud and 36-year-old Bacon hit it off almost immediately.

In his book, The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals, and Breakthroughs in Modern Art, Sebastian Smee described their friendship as “the most interesting, fertile—and volatile—relationship in British art of the twentieth century.”

The two painters were opposites in many ways. At the beginning of their friendship, Bacon was a rising star on the British art scene while Freud was still toiling over his canvases in relative obscurity. And toil he did—Freud was painstaking in his work, spending up to several months working on one piece, while Bacon painted much more quickly and instinctually.

But despite their different working styles, they developed a deep friendship and respect that would lead to each artist’s work being influenced—and criticized—by the other.

At the height of their relationship, the two painters would meet daily at the Gargoyle Club, and then the Colony Club once it opened, where they would drink, gamble, and argue the evening away with a coterie of other friends who came and went. While art was the most important thing in their lives, they also lived on the edge with days filled with drink and debauchery.

During that time, the two were spending so much time together that Lady Caroline Blackwood, Freud’s second wife, said, “I had dinner with [Bacon] nearly every night for more or less the whole of my marriage to Lucian. We also had lunch.”

Naturally, given the amount of time spent in each other’s company talking about art, the artists also decided to paint one other. Bacon completed 16 works of Freud, the most influential of which was a triptych of his friend sitting in a chair that became the most expensive piece of art ever sold at auction when it was snapped up for a cool $142 million in 2013. (This record was shattered in 2015 when a Picasso sold for ++$179.4 million.)

But the much more methodical Freud only reciprocated with two paintings. Bacon sat first for three months in 1952 resulting in the Francis Bacon on copper. Freud worked on the second painting of his friend between 1956 and 1957, but it was eventually left unfinished after Bacon stopped sitting for him. (The unfinished work still fetched a respectable $9.4 million at auction in 2008).

“Bacon complained a lot about sitting—which he always did about everything—but not to me at all,” Freud told The Telegraph in 2001. “I heard about it, you know, from people in the pub. Really he was very good about it.”

For a quarter of a century, the friendship burned bright. But, as was most likely inevitable given the two very opinionated and passionate artists, their friendship blazed to an end by the 1970s and it would never recover.

While all missing or destroyed art delivers a deep blow to an artist’s oeuvre, the loss of Francis Bacon was a particularly upsetting one.

Not only was it a seminal portrait in the development of Freud’s style, but, some have suggested, it also was an emotional reminder of his former friend.

After discovering that Freud kept a “Wanted” poster of the portrait (more on that later) hanging next to his studio door, Smee told Artsy, “I knew that he wanted that painting back very much because of its quality, but I also thought it must have been partly to do with the fact that the subject of the painting was this person who had played such a crucial role in his life and in his artistic career.”

With no suspects in the theft, all that was left to do was speculate who could have taken the painting.

A camera crew visiting the exhibit filmed the portrait at 11am; by 3pm, it had been reported missing. Sometime in those four hours, someone had simply unscrewed the piece from the wall and walked off with it, aided by the fact that there were no alarms or cameras in the vicinity. Rather than an organized crime ring or an experienced art thief, Freud always thought the culprit was someone a little more naive, a little closer to home.

“I wonder whether it was taken by a student because it was stolen when the gallery was full of students. Also, for a student to take a small picture is not that odd, is it?” Freud told The Telegraph. He also suspected that the student nabbed it not out of admiration for Freud’s talent, but out of an admiration for Bacon.

Germany has a 12-year statute of limitations on prosecuting crimes like these. Once the statute on the Francis Bacon theft had expired, Freud decided to make one last attempt to recover the painting.

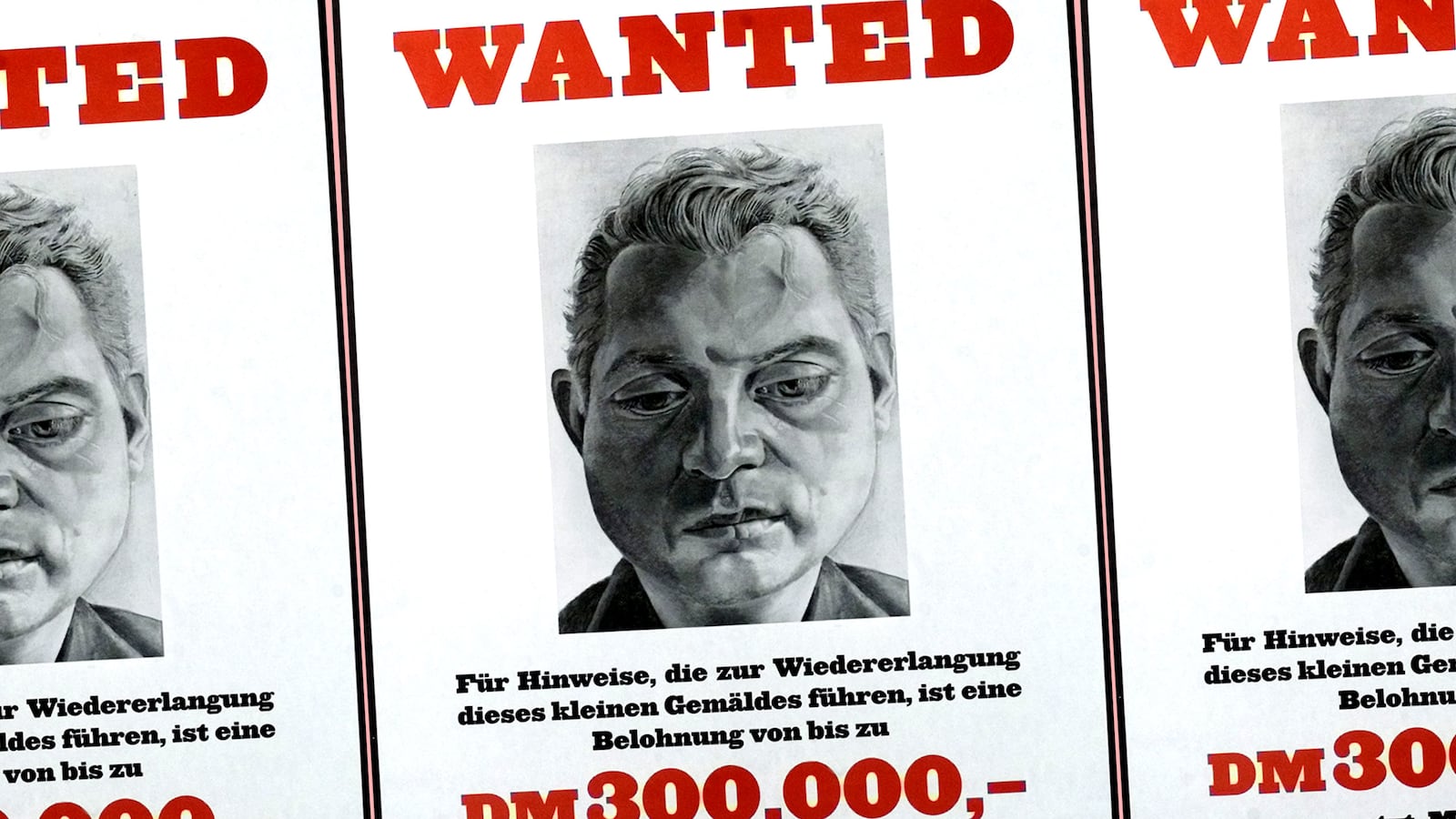

In 2001, ahead of a retrospective planned the following year at the Tate, Freud sketched out a black and white reproduction of the missing painting on a poster that proclaimed “Wanted” in bright red type. “Would the person who holds the painting kindly consider allowing me to show it in my exhibition next June?” the text read above the offer of a reward of over $100,000 for its return and the promise that no questions would be asked.

Around 2,500 copies of the poster were printed and plastered across Berlin but, alas, no one stepped forward to heed Freud’s polite plea. The only thing that came out of the campaign was the aforementioned art on Freud’s wall—one of these posters received a place of honor hung next to the door of the artist’s studio.

The loss continued to sting Freud up to his death in 2011.

From the day it was taken in 1988, the artist only allowed black and white photos of the painting to be shown or printed.

It was a decision he made “partly because there was no decent colour reproduction, partly as a kind of mourning,” the painter told The Telegraph.

It was an artistic—and a symbolic—gesture of loss. “In fact, the painting is quite near monochrome—so it comes out quite well, and I thought it was a rather jokey equivalent to a black arm band. You know—there it isn’t!”