Perfection may be the enemy of good enough—but apparently nobody told that to James Joyce. In Paris in 1920, with the printing of his modernist masterpiece Ulysses already underway, Joyce continued making changes to his 600-page novel, over which he had already labored for seven years. He reworked the manuscript daily, then continued reworking the printer’s proofs—meant to set the novel for printing—as if they were mere drafts, adding about a third of the book after it was already ostensibly complete. The handwritten changes not only necessitated the assistance of a typist to make sense of Joyce’s scrawling, but required rearranging the printing press one letter at a time. Two years of seemingly endless changes drove half a dozen typists to quit and added additional printing costs that ate into nearly 5 percent of what the entire first run was expected to net.

Joyce’s publisher, Sylvia Beach, bore these last-minute alterations as no other publisher likely would have. “The patience she gave to him was female, was even quasi maternal in relation to his book,” said Janet Flanner, The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent, of Beach and Joyce. The publication of Ulysses is just one of the many cases that author Diana Souhami marshals in her book No Modernism Without Lesbians, to effectively argue that, without women like Beach, there would be no modernist men like Joyce.

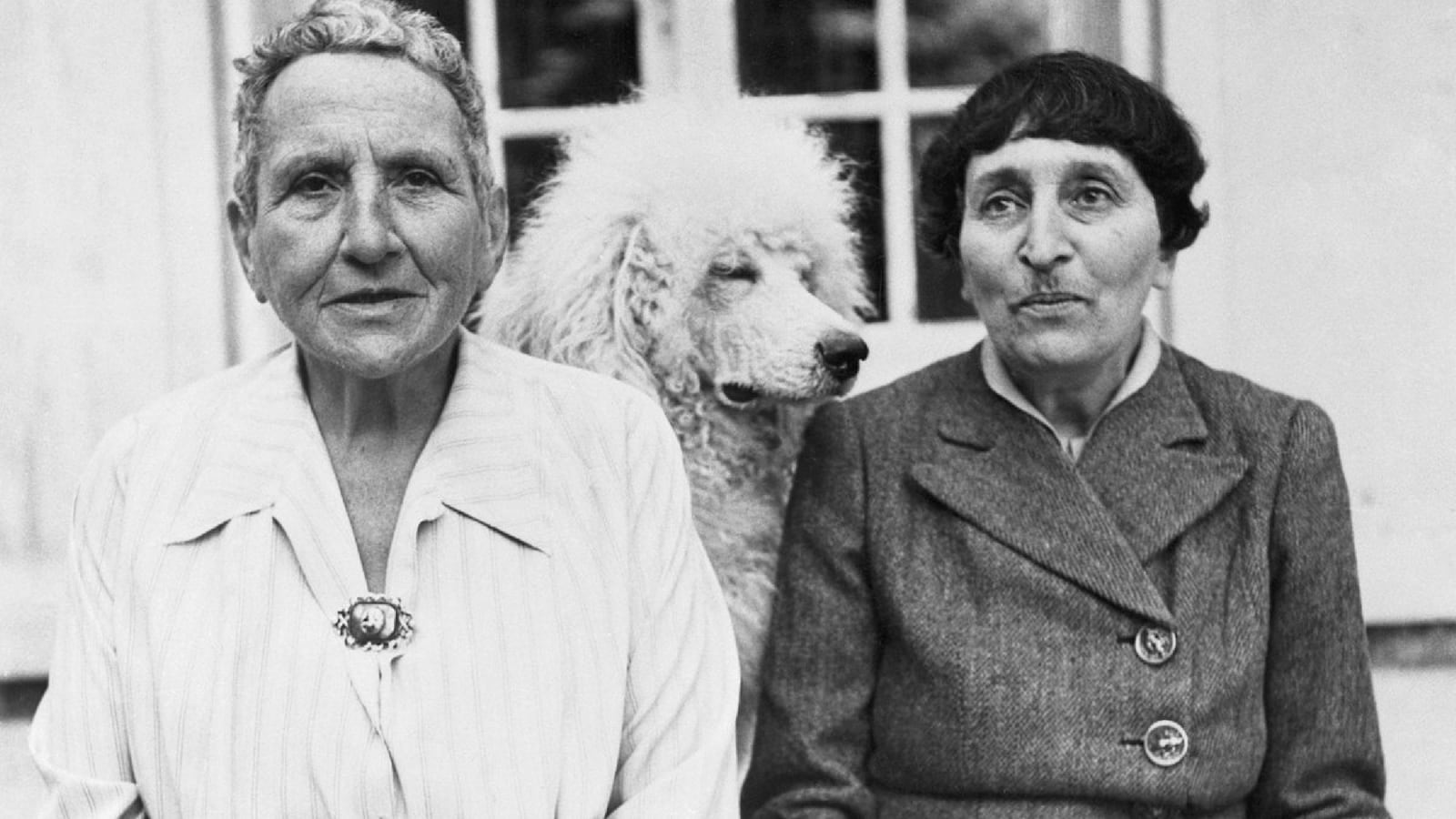

No Modernism Without Lesbians is a collection of four biographies of women who were instrumental to the modernist movement in literature and art: Shakespeare and Co. proprietor and publisher Sylvia Beach, patron of the arts Bryher, author and art collector Gertrude Stein, and socialite Natalie Barney.

Souhami convincingly illustrates how these four women are responsible for the modernist movement, despite it being typically associated with men, such as Joyce and Pablo Picasso. Through Close Up, a magazine about film launched by Bryher, the Western world was exposed to the revolutionary pictures of Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, whose Battleship Potemkin is still considered one of the greatest movies of all time. Besides writing her own books like The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and Tender Buttons, Stein was one of Pablo Picasso’s earliest collectors and a lifelong champion of his work. Barney’s weekly salons brought together up-and-coming writers—including T. S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, William Carlos Williams, and Rainer Maria Rilke—with the French Academy, helping win recognition for the former by the latter. And Beach, of course, had Ulysses as her cross to bear. In that light, No Modernism Without Lesbians could be considered revisionist in the best sense of the word: that of setting the record straight.

“I wanted to turn the issue around,” says Souhami of women’s contributions to modernism, “gain the upper hand, move from campaign and argument for acceptance and civil rights, and show what women in same-sex relationships achieved—singly and, even more so, collectively—in that crucial twentieth-century transition to new ways of seeing.”

The women that Souhami profiles are likewise united by their love of other women: Beach and Adrienne Monnier, Bryher and Hilda Doolittle, Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Barney and, as the author writes, “all her lovers, too many to list.” Despite these well-documented relationships, Souhami acknowledges the difficulty presented by semantics when describing these women, who lived at a time when society prevented them from openly naming their lovers as such, relegating them to mere "friends." The author opts for the term lesbian, but other identities along the spectrum of sexual orientation and gender could also be applicable—such as trans in the case of Bryher, who rejected her birth name and gender from a young age.

Bryher, Beach, Stein, and Barney were further united by their love of interwar Paris. All were expatriates—Bryher from the United Kingdom, the latter three from the United States—who found their way to France in the 1920s. All were pushed from their homes by prevailing efforts to suppress “indecency” in private life and the arts, as typified by Prohibition and censorship. On the other hand, Paris was cheap, as France was still recovering from the carnage of World War I, and Parisian society placed few expectations on expatriates. A comment from Picasso about Beach could stand in for Paris’ perspective of them all: “They are not men, they are not women, they are Americans.”

The freedom that these four women had found for themselves in Paris extended from their personal lives to their artistic endeavors. In Paris, Beach not only found and fell in love with Moore, she published Ulysses, which had previously been thwarted by censors in London and New York. There, as in Paris, publication of the novel was supported by lesbians who were challenging society’s control of what they could read as well as whom they could love. Yet it was only in Paris, where self-actualization and artistic advancement were unfettered by patriarchal control, that modernism could fully bloom. Souhami’s lesbians were seeing themselves differently—as independent, rather than as the daughters, wives, or mothers of men—so why shouldn’t they see the world differently too—through stream-of-consciousness in literature or cubism in painting? The personal and political, the romantic and artistic did not need to be divorced in Paris. As Souhami writes in No Modernism Without Lesbians:

<p>They gravitated to Paris and each other, turned their backs on patriarchy and created their own society. Rather than staying where they were born and struggling against censorship and outrageous denials and inequalities enforced by male legislators, they took their own power and authority and defied the stigma that conservative society tried to impose on them. Individually, each made a contribution; collectively, they were a revolutionary force in the breakaway movement of modernism, the shock of the new, the innovations in art, writing, film, and lifestyle and the fracture from nineteenth-century orthodoxies.</p>

If Souhami’s revisionism succeeds in reintroducing the role of women in the history of modernism, it leaves other questions yet begging. The first is the less flattering aspects of some of her subjects—for example, Stein’s relationship with, and early support for, fascists in Spain and France, which Janet Malcolm details in her biography Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice, but Souhami mentions only in passing. The second is the question of women of color, who make occasional appearances in No Modernism Without Lesbians—such as Josephine Baker, who was redefining dance in Paris in the ’20s—but whose general absence becomes especially noticeable when Souhami begins tracing Barney’s lovers, and Barney’s lover’s lovers, a long list of white women.

“Availability of research material was one limiting factor,” says Souhami in explaining the absence of women of color in her work. “Another was the reluctance of mainstream publishers to commission books about little-known people. I hope, despite this, I’ve made a contribution.”

No Modernism Without Lesbians is undoubtedly a contribution, correcting the history of modernism to more accurately account for the women who made possible such a lasting transformation in literature and art. Yet despite the strides taken by Bryher, Beach, Stein, and Barney, it’s evident that there’s still a way to go. Souhami says that, after decades of her writing about lesbians, this was the first time that a mainstream publisher was open to using the word on a book cover. With No Modernism Without Lesbians, Souhami has opened the door to history a little further, creating more precious space for the whole truth to enter.