On April 19, we will commemorate—as well we should—the twenty-sixth anniversary of the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. But April 19 is also the anniversary of another consequential, albeit lesser known, bombing: On that date in 1960, a bomb went off at the home of Alexander Looby, the Black lawyer representing students and other activists arrested in sit-ins aimed at integrating downtown Nashville. Looby and his family survived, but the bomb blew out 147 windows at a nearby medical college.

The sit-ins had been going on for several weeks. Leaders of the movement, brought together by the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith and trained in nonviolent direct action by James Lawson, included a who’s who of future luminaries: John Lewis, Bernard Lafayette, James Bevel, and C.T. Vivian hailed from the American Baptist Theological Seminary; and Diane Nash and Marion Barry were from Fisk University.

The early morning bombing led these leaders to immediately organize a march. Within a few hours. some 4,000 people descended upon City Hall, where Nash and Vivian confronted Mayor Ben West. Less than a month later, an agreement to desegregate lunch counters was reached—the first in a city below the Mason-Dixon line. Martin Luther King Jr. called the effort “electrifying.” The Nashville Movement, he said, was “the best organized and most disciplined in the Southland.”

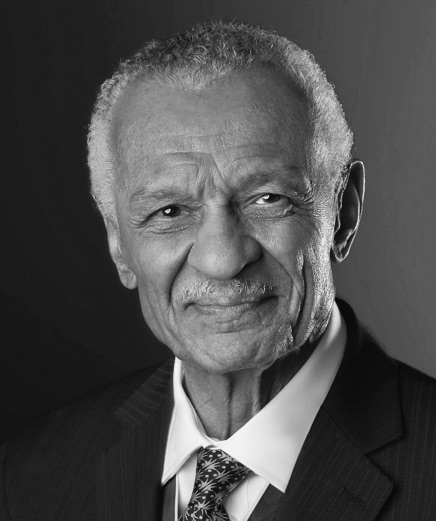

Dr. Vivian, who would go on to play seminal roles in the Freedom Rides, Birmingham, and Selma (and then create the model for Upward Bound), had moved to Nashville from Peoria, Illinois, with his wife and two young children in 1954. By 1960, he had graduated from seminary and was serving as pastor of the First Community Church. With Rev. Smith, he had also formed the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference (NCLC), the first regional chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Called by his good friend Dr. King, “the greatest preacher to have ever lived,” Dr. Vivian, who passed away last July at 95, was also a wonderful writer. I had the privilege of collaborating with him on his recently released memoir, It’s in the Action: Memories of a Nonviolent Warrior. The following is an excerpt about the underappreciated Nashville Movement from the book.

The headline in the Nashville Tennessean read: “Negroes Served Without Incident: Downtown Lunch Counters Open to All.” Think about this: In May 1960—some 170 years after the ratification of the Constitution’s Bill of Rights, almost a full century after the end of the Civil War—it was news that black-skinned people in a city that billed itself as the “Athens of the South” were for the first time afforded the same basic right to sit at a lunch counter as their white-skinned counterparts. Moreover, the Tennessean’s editors found it equally newsworthy that this historic event passed without incident. An angry white mob didn’t shout epithets at the Negroes. The police didn’t drag the Negroes out. The world didn’t stop turning.

How did this happen?

After forming NCLC, we determined that our efforts should be directed at desegregating downtown Nashville, beginning with the lunch counters. Why lunch counters? Blacks could shop in downtown stores, but we could not eat at their lunch counters. Eating is a basic need, right? So demonstrating—through nonviolent direct action—that such a basic need can be denied to a person because of his or her race provides a graphic illustration of injustice….

Jim Lawson, who had gone to India to study Gandhi’s philosophy and methods, began teaching nonviolent resistance to a group of us at SCLC/NCLC in late March 1958. Here we simulated attempts to integrate venues that were segregated. Jim stressed that if/when confrontation arose, we should respond with love and compassion.

Through these workshops we came to understand the philosophy behind the great religious imperatives so important in terms of understanding people. At the same time, we learned the tactics and techniques of nonviolent action. We learned how to take blows, how to resist fighting back when spit upon or when cigarettes were put out on us. Yes, cigarettes! We learned to respond with dignity and love because that was the righteous thing to do and the best way to realize the goals of our continuing struggle for respect and equality.

We actually practiced how to take these blows by knocking each other around. I remember an exercise where someone was instructed to put out a cigarette on one of the participating ministers. An ash fell and burned a hole in the brother’s pants. He held his tongue and fists with his oppressor, but he did tell us that we’d have to buy him a new suit!

Once our band of older activists, ministers, and students coalesced, we set about very deliberately to integrate downtown Nashville.

Step One. Pre-protest persuasion. In November 1959, we attempted to convince the major department stores, Harvey’s and Cain-Sloan, to integrate their lunch counters before we need demonstrate. In addition to making a moral argument, we said that opening up the counters would open up a whole new stream of revenue. The owners countered that the number of white customers they would lose would be greater than the number of Black customers they could gain.

Step Two. Test runs. A handful of students went into Harvey’s in late November and Cain-Sloan in early December. They bought a few things in the stores and then made their way to the lunch counters where they were denied service.

Step Three. Action.

A timeline:

Monday, February 15, 1960. The Baptist Ministers Conference, which represented about eighty congregations, throws its support behind the movement. Black religious leaders urged citizens of all colors to boycott stores that engaged in segregation.

Thursday, February 18. Upward of eighty students are denied service at four different stores. They sit for a while, then leave without incident.

Saturday, February 20. About 350 sit in at several stores for about three hours.

Saturday, February 27. Push comes to shove, literally. Whites attack those students sitting in at two stores. By the time the police get there, those who did the beating are gone. “OK, you nigras, get up and leave,” say the cops. When the students—eighty-one in all—refuse the police order to leave, they are arrested on charges of loitering and disorderly conduct.

Movements need more than a justifiable anger. There must be a strategy and a goal. What you want for yourself and your children and the next generation is more important than having some bad feelings. That is why we were able to enact nonviolent direct action as opposed to swinging back. You have to ask: What are you willing to commit to in order to make something happen? One group of students was arrested, but then a second wave took their place at the lunch counters. And when that group was arrested, in came a third wave.

When those opposing us realized we were coming back every day, they changed their response. The Klan types in the city began to frequent the lunch counters where we were sitting in. That’s when our training proved to be most helpful—because they began to attack, put out cigarettes on people, pull people off their stools and beat them, and pour things on people. Our students were ready, and they sat there.

Our efforts began to resonate in the larger Black community after the police started putting people in jail. Folks came forward to put up their houses as bail. A mass meeting started on a large scale. Now the movement was cooking.

The demonstrations created in many white people a fear of what was possible if Blacks united. Naturally, because of their own racism, they were afraid of anything that Blacks did, because they (whites) were oppressors. They were always afraid of the oppressed, which created a dynamic in the city. But you see, here’s where nonviolence saves us again; because no matter what they said, the oppressed were moving against the oppression with nothing in their hands with which to destroy, but something in their heart.

Because there was nothing in our hands, they could not then react to us in the ways that the Old South normally did. They either had to accept this new loving Black man and woman, or reject themselves. Now they were caught in that kind of dilemma. Black people, on the other hand, had found a method whereby they could rejoice and yet not have any attempt to destroy the other, but only open up the society fully to everyone.

Monday, February 29. The trial of those arrested begins. Well over one thousand community members turn out to support the students. The lead attorney for the students is Alexander Looby. The judge dismisses the loitering charges, but the students are convicted of disorderly conduct and fined $50 each [about $440 today]. They choose to go to jail instead of paying.

Thursday, March 3. Mayor West forms the Biracial Committee, a group of city leaders (including local Black college presidents, but none of the students) to address the sit-ins and the overall racial divide in Nashville.

Tuesday, April 5. The committee issues its recommendations: Stores should have two kinds of lunch counters; one for Whites only and one for Blacks and any Whites who might choose to join them. We at the NCLC said, no thank you. So did the students.

We now complemented the sit-ins with an Easter Boycott of the downtown stores. This allowed us to show our desire to be fully integrated into the life of the city, to demonstrate many ideas of nonviolence, and to help create a reconciliation of all the forces in Nashville. Our theology taught us that those resources that God gave you could not be used to perpetuate an evil. So putting those resources in the hands of merchants who were perpetuating the evil of racism was against God, a misuse of that which was given, number one.

Along with Christmas, Easter was our most important time for buying. No matter how poor you were, everyone in the Black community had to have a brand-new outfit. You may start paying three months ahead of time for that outfit, and you may still be paying for it for three months later.

Of course, Easter was also the time of the cross, a time of sacrifice. Our people found they did not need new suits, new clothes, new shoes. As one woman said, “I looked in my closet and found I had fourteen pair of shoes, and I said, ‘I am so glad for the movement, ’cause I don’t need to buy anything.’”

The merchants could no longer count on getting back the money that they had spent for Easter inventory. The two Nashvilles system wasn’t going to work anymore.

Tuesday, April 19. A group of movement leaders—students and ministers, including myself—were to hold a morning strategy session near the Fisk campus. Before we got there—around 5:30 a.m.—most of us heard a huge explosion.

We knew we had to respond to the bombing of Lawyer Looby’s home. Such an act demanded that the city fathers come to terms with the moral bankruptcy of existing policy—even if they didn’t countenance the bombing itself. Throughout our history, we have been compelled to view such heinous deeds as opportunities; as terrible as it was, this violent act could be very useful to our nonviolent movement. How could we channel the energy we were feeling to accomplish our goal of ending segregation in the city?

We decided to mobilize students as well as the community at large for a march to city hall. We prepared a statement to be read aloud when we got there. And we determined that Diane Nash and I would speak for us.

You see, we were prepared for this moment—didn’t welcome it, but were prepared. This would be the first major march of the modern civil rights movement.

We began the march right after lunchtime at Tennessee A&I on the city’s outer limits. Students came out from the lunchrooms, buildings, and dormitories as we started. We marched three abreast, with Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, and me in the first row. People along the way began to join us in small numbers. They knew this was serious.

When we got to 18th and Jefferson, Fisk students were waiting and fell right in. One block later, students from nearby Pearl High School joined us. Then people started coming out of their houses. Everyone was enthusiastic. At the same time, there was a certain seriousness, an undeniable collective sense of purpose. Eventually our line would stretch ten full blocks.

We had sent a telegram to Mayor West saying that our march would be nonviolent. When we arrived at about 1:30, he was waiting for us on the steps. A forty-nine-year-old former assistant district attorney, West was more progressive than most mayors in the South. But he had not exerted the moral authority of his office to effect the desegregation that we were demanding.

I recently discovered a copy of the April 20, 1960 Nashville Tennessean. The front-page story was written by a young reporter just beginning what would be an illustrious career, David Halberstam. Here are some choice excerpts of his piece, which ran under the bold headline: INTEGRATE COUNTERS-MAYOR.

Mayor Ben West told three thousand demonstrating Negroes yesterday he thought Nashville merchants should end lunch counter segregation, but the mayor standing in front of the courthouse, surrounded by a sea of Negroes which overflowed into the street added: “That’s up to the store managers, of course, what they do. I can’t tell a man how to run his business.”

The Negroes then applauded the mayor. The applause contrasted sharply with the stony silence with which the crowd had watched the mayor moments before as he exchanged heated words with several of their leaders. The sharp words came as the Reverend C. T. Vivian, Negro leader and pastor of First Community Church, read a group statement sharply critical of West for what it termed his failure to lead.

West, his hat off and his voice carrying, said: “I deny your statement and resent your statement and resent to the bottom of my soul the implication you have just read.” He tried to continue speaking, but Vivian shouted in his ear: “Prove it, Mayor, prove the statement is wrong.”

Only a third of the line had arrived when Vivian started reading the Negro statement. That statement accused the mayor of several wrongs, including failing to use the moral weight of his office to speak out against the hatemongers, being difficult to reach, and trying to slow things down until the students went home for the summer.

Then Vivian read: “Because he has failed to speak, we ask that he now consider the Christian faith he professes and the democratic rights of all our citizens and declare for our city a policy of sanity based on our common faith and our democratic principles.” When Vivian finished, the Negroes burst into prolonged applause.

Then West spoke. First he said he deeply resented the implications of the statement. Vivian, by his side, seemed to argue with him several times. Vivian was later restrained by another Negro minister. “I intend to see that order is maintained,” West said. “As God is my helper, if anything can be done to find the man who bombed my good friend Looby’s home, we’ll do that.”

The crowd was still gathering. West was pocketed among a group of the Negro leaders. Vivian started the questioning. He asked the mayor if segregation were moral. “No,” the mayor said. “It is wrong and immoral to discriminate.”

Then, Miss Nash asked West to use “the prestige of your office to appeal to all the citizens to stop this racial discrimination.”

West answered: “I appeal to all citizens to end discrimination, to have no bigotry, no bias, no hatred.”

Miss Nash asked: “Do you mean that to include lunch counters?”

West answered, “Little lady, I stopped segregation seven years ago at the airport when I first took office, and there has been no trouble there since.”

But Miss Nash asked one more question: “Then mayor, do you recommend that the lunch counters be desegregated?”

That is when West answered: “Yes,” turned slightly and added, “That’s up to the store managers, of course.”

(I couldn’t stay silent. Halberstam would later write: “More than any of the other Nashville ministers, Vivian seemed able to provoke the anger of his adversaries. He was intense and outspoken—C. T., his wife, Octavia, once said, in a masterpiece of understatement, gave long answers to short questions.”)

Then Vivian asked, “Do you realize that this goes deeper than the lunch counter, that it can destroy us?”

West answered: “You also have the power to destroy. I want you students to realize this . . .”

Vivian then asked: “Is segregation Christian?”

West told Vivian to look at his past record. “What a fellow does often speaks so loud you can’t hear his words.”

Vivian said he was not asking about the past record.

A postscript is required.

Tuesday, May 10. At 3 p.m., groups of two or three Blacks, mostly students, enter six Nashville department stores and take their seats at the lunch counters—the lunch counters that had previously only been open to white patrons. Among the items they order: club steaks and hamburgers. As the Tennessean would report, one store official said, “There was no reaction whatsoever from our white customers.”

Over the previous weekend, we had finally reached an agreement with the store owners. It was far different from the earlier plan proposed by the Biracial Committee. Blacks would come to the counters in small groups at slack hours for several days so that integration could be introduced gradually, in a less threatening fashion, to avoid confrontation or violence.

The plan worked. And then, as John Lewis put it, we began a march through the yellow pages to integrate other public venues. The march took time. A year passed before we achieved another major milestone: integrating the downtown theaters.

I remember that because the victory was celebrated with a picnic on Mother’s Day in 1961—the same day that Klansmen attacked the Freedom Riders in Anniston, Alabama.