In James Grady’s novel Six Days of the Condor (which became the Robert Redford movie Three Days of the Condor) Ronald Malcolm, Redford’s character, works for the CIA. His job is to read spy novels. He looks for any tricks in spy fiction that the CIA could use, and he tries to spot whether the writers, might, in fact, know something—are they perhaps revealing tactics that some espionage service actually employs?

Grady made this job up; he wanted to show a complete nerd morphing into a man of action. Reading books all day seemed like the nerdiest possible CIA job.

Grady was unaware until many years later that his idea had taken life. Sergei Tretyakov, a former KGB intelligence chief in Manhattan, defected to the U.S. in 2000, and eventually collaborated with writer Pete Early on a book, Comrade J. One of Tretyakov’s first KGB jobs, he said in the book, was rooting through the Western press at a new analysis unit in Moscow called the Scientific Research Unit of Intelligence Problems. It was founded because several KGB generals saw Condor and decided the CIA was putting more effort into analysis than the KGB was.

They didn’t realize that Malcolm’s office didn’t actually exist. “They wanted to glean good ideas and figured their opponent the CIA was doing it, so they had to do it too,” Grady said. “It was literally the era of move and countermove.”

Here is an example of real espionage imitating spy fiction about real espionage getting clues from spy fiction that might have been written about real espionage.

Espionage and espionage fiction are like two facing mirrors, an endless reflection. The Venezuelan terrorist Carlos was named “the Jackal” because when he was caught, he was reading Frederick Forsyth’s Day of the Jackal.

Just as members of the real mafia have taken their behavioral cues from Goodfellas or drug dealers from Scarface, spies consciously model themselves on their more famous—and often more interesting—fictional avatars. John Le Carré, especially, has strongly influenced the secret service vocabulary. He brought us “honey trap,” “scalphunters,” “babysitters,” and “lamplighters.” He claims he did not invent “mole,” which has now become common parlance for a sleeper agent burrowed deep into the heart of enemy intelligence. Le Carré says that “mole” was an old KGB term—but not everyone believes him.

We are used to the idea that spying begets spy novelists. Le Carré, Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, and Graham Greene all drew on their time in Britain’s secret service for literary profit. But there is at least one spy novelist who went in the other direction.

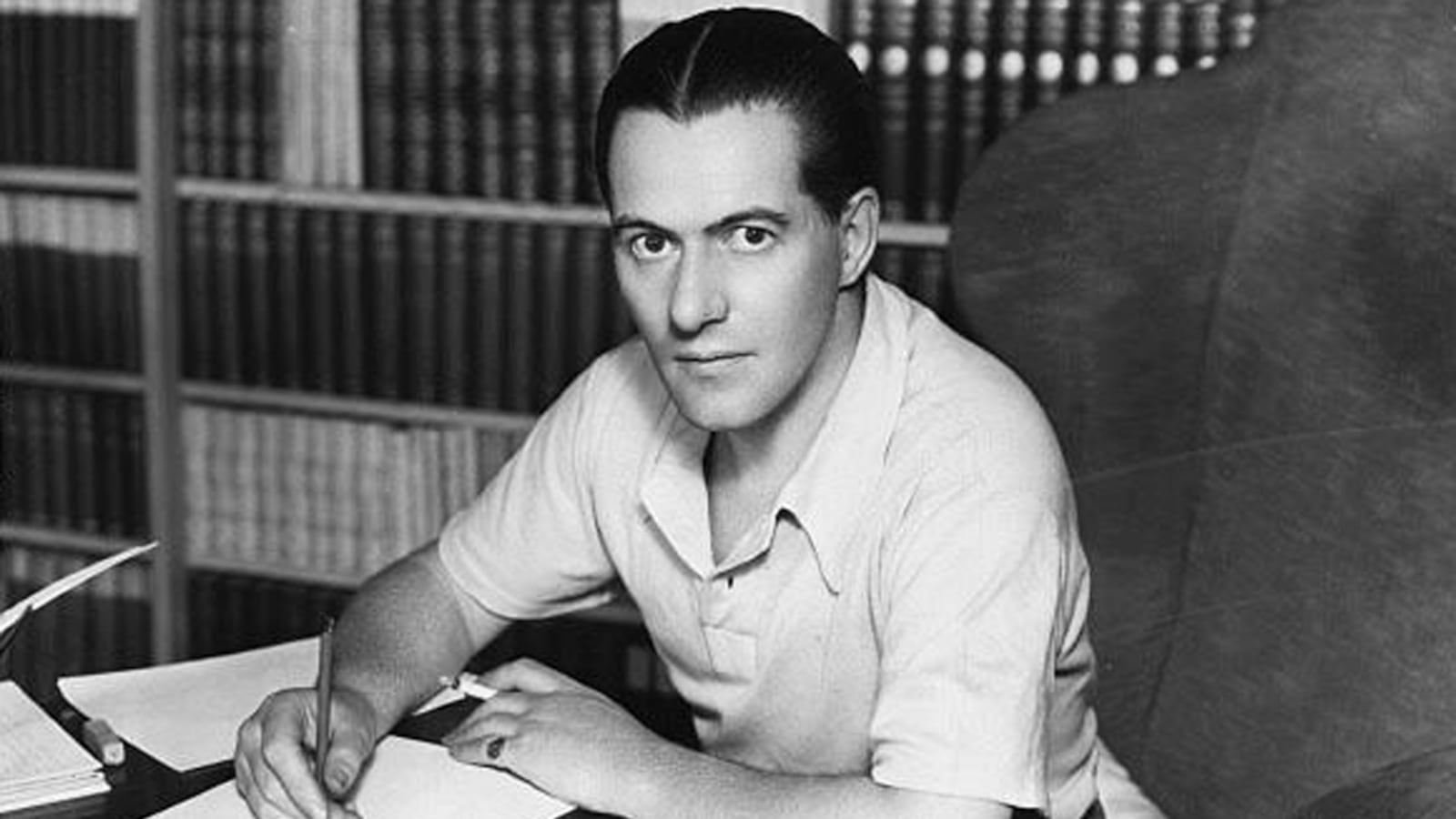

In the 1930s Dennis Wheatley was Britain’s most popular thriller writer. As the war began, he started a series of novels featuring secret agent Gregory Sallust. Before there was James Bond, there was Gregory Sallust. Sallust is ruthless and charming, a connoisseur of rare wines and rare women. Most important, he speaks German like a native. In book after book, Sallust dons a German uniform and infiltrates the Nazi machine—in one case, stealing the identity of the head of the Gestapo’s foreign section.

As happens in books like these, Sallust pretty much single-handedly wins the war. During a long, drunken night dissecting the map of Europe with Hermann Göring, Sallust steals a document that keeps Britain from surrender in her darkest days. He tricks Hitler into invading the Soviet Union. He dazzles Göring, and everyone else he meets, with his military assessments. His knowledge is encyclopedic, his strategic analysis brilliant. He is a master of deception.

Then at the end of 1941, Dennis Wheatley stepped into the pages of his own novels.

He went to work in Churchill’s bunker—the only civilian to be recruited onto the Joint Planning Staff. His mission was to deceive Hitler. Wheatley was part of a tiny group of deceivers—at one point, he worked alone—who thought up cover plans for Allied operations and ruse after ruse to make the Germans believe them. Their greatest achievement, of course, was that on D-Day, the Allied invasion of France took the Germans completely by surprise.

When Wheatley joined Churchill’s staff, he had already planted himself inside the head of the enemy—“Gregory and I had been looking pretty closely at the Nazis for quite a while,” he told an interviewer. And he had been inventing strategic deceptions for Sallust for years. But deception was familiar to Wheatley on a different level as well. Deception involves first choosing a story—story is actually the term of art—that will be your cover plan. Then you break that story into tiny pieces and draw up a schedule for spooning it bit by bit into the maw of the enemy—which morsel fed by what channel on what date. Not too obvious—give him the telling detail and let the enemy make the connections on his own. That is how to write a deception plan. But it is also how to write a novel.

The deception planners borrowed from fiction, including for one of the most celebrated operations of the war: Operation Mincemeat. A body dressed like a major in the Royal Marines was pushed out of a submarine near the Spanish coast, carrying a letter designed to fool the Germans about the coming invasion of Sicily.

The idea behind Mincemeat came from a detective story. In the 1937 novel The Milliner’s Hat Mystery by Basil Thomson, the hero, Inspector Richardson, finds a body in a barn. All the documents on the body have been forged; Richardson’s task is to find the man’s real identity. The idea stayed with a young Naval Intelligence officer who owned all of Thomson’s detective stories: Ian Fleming.

Fleming’s novels would come later—his first, Casino Royale, was not published until 1953. During the war he was a colleague of Wheatley’s, and a guest at his dinners. That James Bond greatly resembles Gregory Sallust is not an accident.

Dennis Wheatley’s books sold more than 50 million copies over his lifetime. Yet today his books have disappeared: unknown in America, largely forgotten even in Britain. What will last forever are his other fictions—the stories he wrote from Churchill’s bunker, aimed not at millions of readers, but at only one.