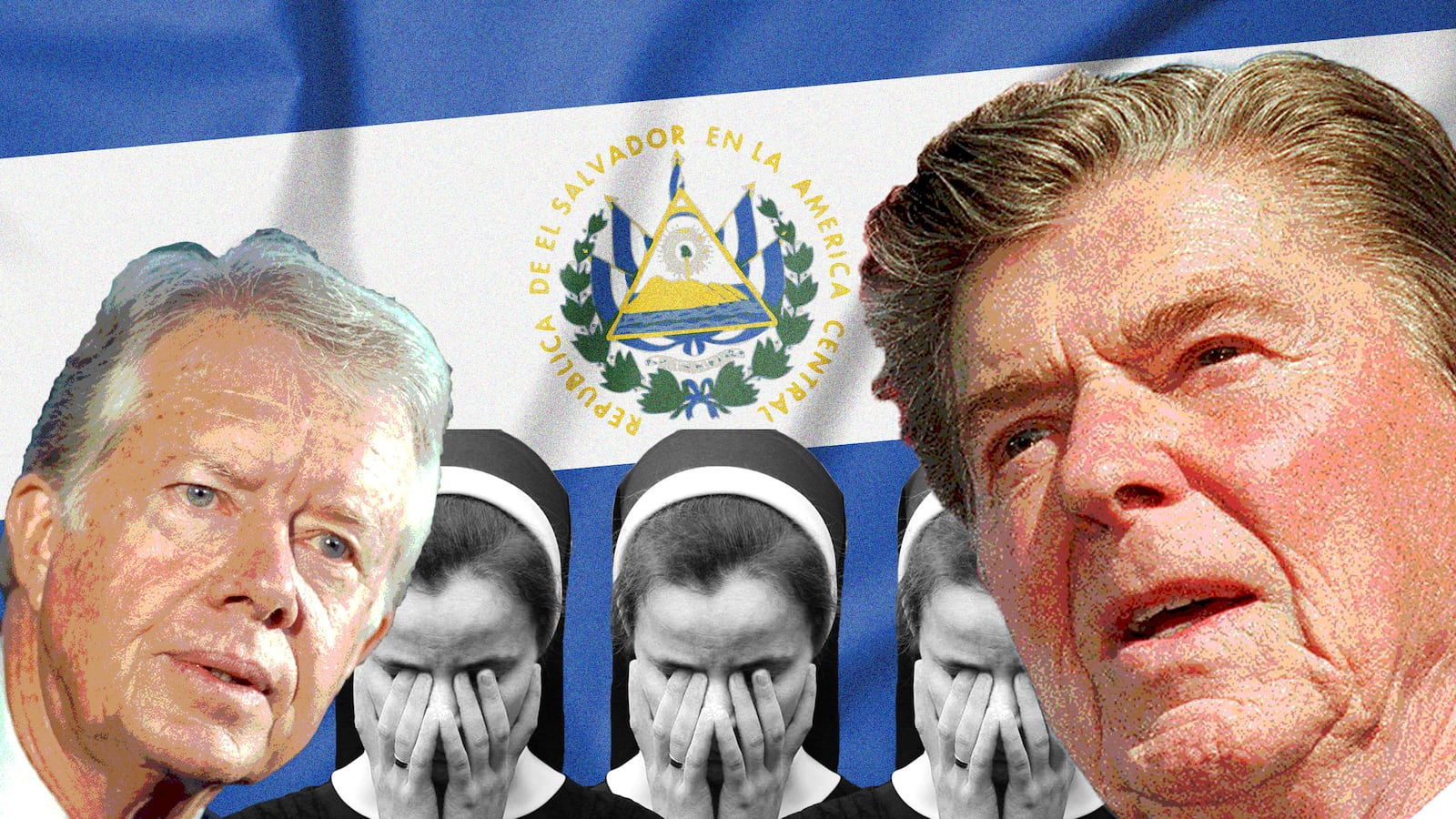

PARIS — A new president had just been elected in the United States — a hard line president, who, it was said, had no patience with the vacillating, moralizing policies of his predecessor. Around the world thugs who would spit when they heard the phrase “human rights” suddenly took heart. With such a man in the White House, they thought, they had a license to kill.

This was November 1980, when the confused transition from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan opened the door to a bloodbath in the little Central American country of El Salvador; when, suddenly, anyone the military suspected of aiding the subversivos was liable to be tortured to death, and even Americans—even American nuns—were fair game.

Now 36 years later, we will soon mark the anniversary of the death of four American churchwomen kidnapped, raped and murdered in El Salvador on the night of December 2, 1980.

It is not the first occasion for commemoration, nor will it be the last. The memories of Sister Maura Clarke, Sister Ita Ford, Sister Dorothy Kazel and young lay worker Jean Donovan have been brought back to us again and again in articles, tributes, on film, and most recently in the excellent just-published biography A Radical Faith: The Assassination of Sister Maura, by Eileen Markey.

But these worthy efforts do not capture, quite, the sense of lawlessness that existed among the most savage elements of the Salvadoran military after Reagan was elected and before he actually took responsibility for, well, for anything.

It’s a cautionary example now as we look at the kind of Neo-Nazi crazies who claim to have found in President-elect Donald Trump a kindred soul, and the tyrants (Assad, Putin) who may think Trump will give them a pass on their ferocious repression.

In El Salvador in 1980 one learned the greatest danger was not only what American politicians say, but what others around the world think they hear.

***

A week after the churchwomen were murdered, Robert White, the embittered U.S. ambassador to El Salvador invited me and Raymond Bonner, correspondents for The Washington Post and the New York Times respectively, to talk on the record about what was dubbed a “hit list” leaked a few days earlier by someone on the Reagan transition team. It named so-called “social reformers” in the diplomatic corps slated for removal from their posts.

White, a distinguished career diplomat, had known the nuns personally. He dined with Kazel and Donovan the night before their murder, and he had seen them exhumed from their shallow grave in the Salvadoran countryside two days after that. He gripped the arms of his chair as he spoke about the incoming administration’s putative representatives who were telling the Salvadoran military to ignore official denials of Reagan support for a coup.

“When civil war breaks out in this country, I hope they get their chance to serve,” said White.

The U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua, Lawrence Pezzullo, summed up the situation throughout the region. “It's going to be our ideological blinders that may cause us to make mistakes," Pezzullo told me as he considered Central America policy under the incoming president. "This is a new administration, there are going to be tradeoffs, and you've got to feed your right-wing somewhere.” Central America was tiny and proximate. Pezzullo paused and reflected for a moment. "That's the way I tend to think things will go," he said, "just feed it to the lions."

***

White had arrived in the capital San Salvador in the middle of March 1980, picked for the job because he believed in the Carter administration’s defense of human rights, not as a sop to communists, but as a bulwark against them.

The previous year in nearby Nicaragua, the Somoza dynasty was overthrown in a popular uprising spearheaded by Marxist-led rebels who called themselves Sandinistas. Now the administration was concerned the rest of the region would fall to similar groups, picking off one country after another like ripe or, in fact, rotten fruit.

White’s thankless job in El Salvador was to try to create a center in a country already divided by a history of bloody violence dating back to the infamous matanza of 1932, when a peasant uprising lead by Farabundo Martí was crushed by a dictator named Maximiliano Hernández Martínez — names adopted respectively by the guerrillas and the death squads of the 1980s.

Soon after White landed, he wrote a 27-page cable, recently uncovered by my old friend Bonner, that began, “There is no stopping this revolution; no going back. In El Salvador the rich and powerful have systematically defrauded the poor and denied 80 percent of the people any voice in the affairs of their country.”

There was nothing naïve or sinister about this, although many Reagan supporters would say there was. White’s concern was that so few paths of moderation were open, “an extremist Communist take-over here, and by that I mean something just this side of the Pol Pot episode, is unfortunately a real possibility due to the intense hatred that has been created in this country among the masses by the insensitivity, blindness and brutality of the ruling elite.”

In the 1970s, much of the opposition to the government had been lead by priests and nuns organizing the poor into what were called “base communities.” One of the most outspoken clerics had been a Jesuit named Rutilio Grande who gave a famous homily in 1977 warning that “very soon the Bible and the Gospel will not be able to come across our borders. We will get the covers, nothing more, because all the pages are ‘subversive.’”

Grande told his flock that if Jesus of Nazareth came to El Salvador he would be “crucified all over again.” Shortly afterward, Grande, along with an aged campesino and a teenager, was slaughtered in a hail of automatic weapons fire.

The murder and persecution of religious figures grew so intense that the hitherto conservative archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Arnulfo Romero, began to speak out stridently against government oppression, becoming the voice of the poor and of opposition.

In March 1980, Romero called on El Salvador’s soldiers to lay down their arms. The next evening, he was killed with a single bullet through his chest as he said mass in the chapel of the hospice where he lived.

Ambassador White had been in El Salvador less than two weeks.

At Romero’s funeral, more than 40 people were killed, mostly crushed to death in a panicked stampede trying to find shelter when shooting broke out in the cathedral square.

In the weeks and months that followed, it was commonplace to see cadavers in the streets, sometimes horribly mutilated, sometimes looking as if they were merely sleeping off a long night drinking Tic-Tac, the alcoholic escape of the poor. But there were no vultures around the drunks. And one grew used to distinguishing the smell of death.

By then, the political campaigns were in full swing in the United States and Ronald Reagan was well on his way to sealing up the Republican nomination. Carter had been weakened and humiliated months before, when the Ayatollah Khomeini’s minions took hostage most of the U.S. embassy staff in Tehran. Then, when a rescue mission ended in disaster in the Iranian desert, Carter’s presidency was doomed.

On election night, November 4, 1980, the embassy gave a party at the Hotel El Presidente in San Salvador, and the mood among the American diplomats was somber. But among members of the Salvadoran military officers and oligarchs who attended, there was outright jubilation. Some of the officers outside fired their guns in the air. A couple of American envoys, as they walked to their cars, had to run a gauntlet of high-heeled, bejeweled señoras shouting, “We’ve won!” and “Get out of here.” “Communistas!” the women called them. “Death to White!” and “Viva Reagan!” they shouted.

To the extent there had been any limitation on the slaughter, those inhibitions were about to drop away.

***

Carl Gettinger, a young U.S. embassy political officer, was at the El Presidente that election night and still remembers the women and their curses.

“The election of Ronald Reagan gave the ‘right,’ whether civilians or the more or less right wing of the Salvadoran military, the signal that the gloves were off,” says Gettinger.

He is retired now after a long career in the foreign services and happens to live in Paris, where we met at a café last week to talk about those grim old times.

“They suddenly thought, ‘We don’t have to abide by all these regulations and restrictions and the Mother Hubbard advice from fuddy duddy Jimmy Carter,’” Gettinger recalls. They thought, “It’s a dream come true for us. Now we can really go after the ‘communistas.'”

In mid-November, as Markey writes in her exhaustively researched book on Sister Maura, Salvadoran Defense Minister José Guillermo García called the civilian members of the civil-military junta to a meeting at the presidential palace. “There he made a half-hour-long presentation meant to prove that the nuns and priests in Chalatenango were collaborating with the guerrillas.”

That province north of the capital was where Sister Maura and Sister Ita worked, and they were indeed helping the guerrillas by smuggling their families to refugee camps and eventually bringing food and medicine to the war zone.

Although the guerrilla faction in the area, the Fuerzas Populares de Liberación "Farabundo Martí" (FPL), probably was the one White had in mind as trending toward Pol Pot, by then, as Markey writes, “the guerrillas were the people. Driven by conscience, people the whole country over were doing everything they could to protect themselves from a campaign of extermination.”

“In the deeply hierarchical culture of the Salvadoran military,” Markey concludes, “the minister of defense’s making an accusation against individuals was tantamount to an execution order.”

•••

The Sandinistas and Fidel Castro were watching the U.S. presidential transition as well, and encouraging the Salvadoran guerrillas to make a bid for all-out insurrection, presenting Reagan with a fait accompli before he took the oath of office. A year earlier, in January 1980, hundreds of thousands of people had poured into the streets to protest against the government. Now, if they would do that with guns in their hands, they could take over the country.

The U.S. embassy’s last, frail hope for a political settlement that might avoid civil war involved negotiations with the Democratic Revolutionary Front (FDR), a coalition of militant organizations and labor unions allied to the various guerrilla factions and presided over by Enrique Álvarez Córdova, one of the few members of the Salvadoran oligarchy whose conscience and political sense told him that the killing must stop and dialogue must prevail.

As the FDR leaders met in a Jesuit high school on November 27, 1980, a commando of heavily armed men in plain clothes broke in on them and marched them off to their deaths. Their mutilated bodies were found scattered around San Salvador the next day.

It was Thanksgiving weekend, but Reagan foreign policy advisor Jeane Kirkpatrick found time to offer her opinion, calling it“a reminder that people who live by the sword die by the sword.”

“I am sure that was ordered by the high command,” says Gettinger as we look out the Paris café window at a flower stall, so distant in time and space from those hideous days. “If you can point to one act where they are saying ‘we are immune now’ at the highest level, that was it.”

The bodies of the FDR leaders were taken to the cathedral to lie in state, but even there they did not rest in peace. The group calling itself the Maximiliano Hernández Martínez Brigade detonated a massive car bomb outside.

The FDR funeral was scheduled for December 3, and Sister Maura and Sister Ita, who had been at a retreat in Nicaragua, flew back to El Salvador’s international airport the night before. Sister Dorothy and Jean Donovan went to pick them up.

Their murderers were watching.

“In Chalatenango,” writes Markey, “someone approached the church sacristan in the movie theater not far from the parish house. He showed the sacristan a list: it named everyone on the parish staff. 'And tonight,' the man said, 'this very night, we will begin.'"

•••

During the Reagan transition, “There was an increased sense of impunity,” says Gettinger, and a spike in the murders across the country recorded in what the embassy called its “grim-grams” back to Washington.

That word “impunity” is not one that you hear very often in English, but impunidad is in common usage in Spanish, and has long been a sordid fact of life—and death—in Latin America. It is the trademark of tyranny, negating “the rule of law,” whether for politicians, soldiers, or, for that matter, today’s drug cartels. And it is a kind of contagion. If the high command believes it can murder with impunity, subordinates on down the line come to believe the same thing.

The FDR funeral was attended by a fearful crowd much smaller than the one we’d seen after the murder of Romero. The terror was working.

The next day the bodies of the churchwomen were discovered in the shallow grave where local peasants had buried them.

The signals out of the transition team just kept coming in language that killers could interpret as license—and El Salvador’s death squads understood them well.

Jeane Kirkpatrick, soon to be Reagan’s ambassador to the United Nations, told a reporter from the Tampa Tribune in December. “The nuns were not just nuns, they were political activists. We ought to be a little more clear about this than we actually are. They were political activists on behalf of the Frente and someone who is using violence to oppose the Frente killed these nuns.” She was asked if she thought the government was behind the murder. “The answer is unequivocal. No, I don’t think the government was responsible.”

***

On January 3, 1981, some 17 days before Reagan’s inauguration, a pair of gunmen entered the restaurant of the San Salvador Sheraton Hotel and opened fire with automatic pistols. Rodolfo Viera and Michael Hammer, who had just arrived from Washington, were killed where they sat. Mark Pearlman struggled to get away but the bullets kept coming, about 40 shots in all, and he died there as well.

Hammer and Pearlman were American land reform experts working for the AFL-CIO's American Institute for Free Labor Development. Viera was head of the Salvadoran agency that oversaw the controversial land distribution that the United States had made a vital facet of its reform policy under the Carter administration.

American investigators eventually concluded the man who ordered the killings that night was Lt. Rodolfo Isidro López Sibrián, known as “el fosforito,” the little match, because of his red hair and hot temper, but they were never able to win a conviction against him in that case.

Indeed, many human rights activists doubted, in the end, that the Reagan administration wanted to pursue investigations that might implicate the senior officers on whom it came to depend as the Salvadoran war erupted and raged on: men like Defense Minister García and then-Guardia Nacional commander (later defense minister) Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova.

Only low-level enlisted men eventually were caught and brought to trial in the nuns case, and even they would have escaped with impunity were it not for Carl Gettinger.

***

In mid-November 1980, shortly after the American elections but before the murder of Americans began, a Salvadoran lieutenant contacted the embassy and Gettinger was assigned to talk to him. The conversation was eye opening. The lieutenant, who became known around the embassy as “the Black Sheep” and “Killer,” seemed to be that rare thing in El Salvador, a military officer with a conscience. He hated the left and the guerrillas, but he hated the right wing as well, feeling the military was exploited by the elites for their own selfish ends.

Over the next few days and weeks, Killer admitted to ordering summary executions, and to operating as part of the death squads organized by retired Salvadoran Major Roberto D’Aubuisson. He talked about the way officers had drawn straws for the privilege of murdering Archbishop Romero.

Although officers far senior to Killer were on the CIA payroll, they were providing no useful evidence, and simply lied about conducting an investigation into the murders of the churchwomen and the labor advisors.

Killer, at first, would not talk about those cases either.

Ten days before Reagan’s inauguration, the guerrillas launched their so-called “final offensive” the length and breadth of the country, but could not bring down the government. The death squads had done their jobs well, eliminating the urban infrastructure of the left and killing off the people who might have negotiated a settlement. So the “final offensive” proved to be just the first major offensive in the all-out war that went on into the next decade.

The incoming Reagan administration, now confronted with the likelihood the war would grow worse, wanted to push the murders of the Americans to the back burner, and off the stove if possible. What was needed for political cover in Washington was a statement from the embassy in San Salvador saying the Salvadoran government was conducting an investigation.

Ambassador White refused. “I will have no part of any cover-up,” he wrote in a very blunt cable to Washington. “All the evidence we have, and that has been reported fully, is that the Salvadoran government has made no serious effort to investigate the killing of the murdered American churchwomen.”

Two weeks after the inauguration, White was dismissed. Shortly thereafter, in March, newly sworn Secretary of State Alexander Haig put forth as the “most prominent theory” of the investigation that the women had been running a roadblock.

Gettinger kept pushing Killer for information on the murder of the nuns, and slowly the soldier revealed details. The Guardia Nacional sergeant who had lead the operation against them, and whom Killer had known personally for many years, was named Luis Antonio Colindres Alemán.

Not only did the high command not act on this information, it scrambled to cover up whatever evidence it could. So in April, Killer took a miniature tape recorder and went for a drive with Colindres Aléman, who confessed to the crime and many of the details.

But that tape, which ought to have been like a Rosetta stone exposing those higher up in the chain of command, was full of unintelligible gaps.

Again and again over the next two years, Gettinger would listen to this “special embassy evidence,” as it was called. Technicians and specialists would try to tease out the meaning of the static- and noise-filled passages, but to no avail.

On the basis of what he actually could hear, Gettinger concluded that Colindres Alemán was “a psychopath” who, believing he had impunity, took the initiative to kill the churchwomen without any explicit orders from higher officers.

This suited the new Reagan administration, which was not going to act against the generals it wanted running the Salvadoran show unless it had irrefutable evidence of direct orders.

In 1983 Gettinger wrote a memo explaining why Colindres suddenly thought he could kill American women with impunity. Colindres had been told by other guardsmen that they were “guerrilla sympathizers, gun runners, carriers of subversive propaganda.” (Much the same line pushed afterward by Jeane Kirkpatrick.)

“The considerations about their nationality which had protected them up to that time seem to have occurred to him,” wrote Gettinger, "but his reaction was merely a crude attempt to cover his tracks.”

“The decision to kill the American churchwomen was made by Colindres and no one else,” Gettinger concluded, and to this day he maintains that the high command did not order the murder explicitly.

“Would even such blockheaded people have thought it was okay to rape and kill four American nuns?” he said as we talked here in Paris. “They were not that stupid. None of the people at that level would say, ‘Let’s go kill some American nuns.’”

Unless, of course, they thought they too could act with impunity—which is what they continued to think they had for the next 35 years.

The sergeant and his soldiers were convicted and jailed, but among the commanders the belief that they were given carte blanche by Reagan transition team lived on into the new administration.

The Salvadoran military grew from 11,000 men in 1979 to 57,000 in 1989, eventually underwritten by billions of dollars in U.S. aid. The toll of the war mounted: 75,000 people died. The Army was always said by Washington to be growing more professional, more conscious of human rights. Then, in November 1989—nine full years after the nuns were murdered—a group of elite, American-trained Salvadoran soldiers slaughtered six Jesuit priests deemed "subversive."

As a U.S. Embassy cable reported in January 1990, "if the system had brought to justice those responsible for the famous 'Sheraton murders' and for the killing of the nuns a few years ago, the signal that such crimes would not be tolerated would have been clear."

Human rights attorneys and investigators would not let the case drop, and slowly, as masses of relevant American documents were declassified, evidence accumulated. A 1984 CIA cable—now available in highly redacted form on the CIA website— cited information from a source who claimed Col. Oscar Edgardo Casanova Véjar had ordered the murder of the nuns. He was the commander of the garrison responsible for the airport, and “had information re the suspected involvement of the nuns in leftist activities. He also knew the date and time of their arrival in El Salvador on the day they were killed. … [Source claimed] that Casanova, who is the first cousin of Minister of Defense Vides Casanova, was transferred to Army HQs immediately after the murder of the nuns to shield him from the subsequent investigation.”

* * *

In 1998, along with human rights attorneys Scott Greathead and Robert Weiner, I interviewed Casanova Véjar, who denied any connection to the murders.

As I wrote then, “Greathead and Weiner were not convinced. To believe Casanova Véjar's contention that he knew nothing, one must assume that in a small command in rural El Salvador, a lowly sergeant like Colindres could take it into his head to deploy 14 men, disrupt traffic out of the airport, target, kidnap, rape and murder four American women religious workers, then leave behind their unburied bodies and their burned-out vehicle with no one the wiser at headquarters. Casanova Véjar shrugged. ‘Something can be happening five kilometers away,’ he said, "and we wouldn't know it.’”

Casanova Véjar was never prosecuted, but Greathead and other lawyers, including those of the Center for Justice and Accountability, working with the families of the murder victims and Salvadoran torture survivors, tracked the former defense ministers García and Vides Casanova to Florida, where they both lived in comfortable retirement.

After many years of court battles, in 2014, Immigration Judge Michael C. Horn determined that García assisted or otherwise participated in some of the most heinous human rights crimes committed in El Salvador in the 1980s, including the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero, the killing of the four American churchwomen and the two U.S. labor advisors, as well as subsequent atrocities. By the beginning of this year, both García and Vides Casanova had been deported back to El Salvador.

Going over the evidence, Horn wrote (PDF), “Dead bodies bearing signs of torture were heaped in piles on the streets of the capital city, along well-traveled highways, in shopping centers, and in parking lots of prestigious hotels. Tortured corpses, some beheaded, some dismembered, were left to decay in the Playon Body Dump, accessible only with the consent of the military.”

Horn noted that García “admitted that the Salvadoran Armed Forces, during his tenure as Minister of Defense, committed extrajudicial killings. Yet [he] rebuffed reform, protected death squad plotters, denied the existence of massacres, failed to adequately investigate assassinations and massacres, and failed to hold officers accountable for killing their fellow countrymen. [García], as Minister of Defense of El Salvador, created an atmosphere of impunity in which members of the armed forces would not be investigated, prosecuted, sanctioned, or discharged for atrocities visited upon civilians.”

There is that word again: “impunity.” As the Salvadoran killers listened to the Reagan transition team, whatever the language used, that was the word they heard.

One hopes the monsters among us today will not draw the same sorts of lessons from the men and women around Trump.