The Manhattan District Attorney’s investigation into former President Donald Trump seems doomed, but a little-known New York law is buying time for prosecutors to build a better case against him and convince the hesitant new DA to act—or wait until he’s replaced.

Law enforcement in New York has five years from the date of an alleged crime to officially file charges for most felonies, but under New York law § 30.10(4)(a)(i), that clock stops for up to five more years when a defendant is outside the state. That 10-year grace period means Trump’s time in the White House and his post-presidential political exile at the Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida may be gifting prosecutors much-needed extra time.

According to sources familiar with the investigation, prosecutors there have been poring over thousands of spreadsheets and financial records from the Trump Organization and slowly building a case against Trump for allegedly inflating property values, lying on business forms, dodging taxes, duping banks, and running his company like a mob.

Those same sources say the team of Manhattan assistant district attorneys has considered the use of the state’s clock-stopping measure in the Trump investigation.

New York law says that “any period… during which the defendant was continuously outside this state” doesn’t count, up to an extra five years.

Adam Kaufmann, an attorney who ran the Manhattan DA’s investigative unit for three years, said he doesn’t remember ever relying on this clock-stopper in his prosecutors’ cases. But he recognizes it as a useful tool—one that would have to appear on any indictment of Trump to establish from the get-go that any criminal charges are timely.

“You don’t often have white collar cases that are so… old. It just doesn’t happen that much that you’re trying to get something from more than five years ago,” Kaufmann said.

But, he added, “it’s easy to prove he was not in the state of New York. There’s going to be records of where he was physically located every day for four years.”

This rarely used time machine of sorts suddenly has heightened importance.

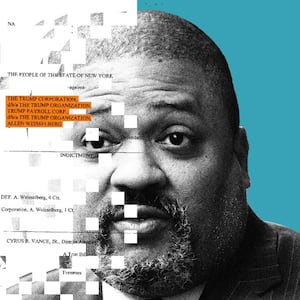

It’s become clear that DA Alvin Bragg Jr. won’t sign off on an indictment against the former president until he can be convinced he has a stronger criminal case. Bragg’s reticence to file charges against Trump himself prompted the two top prosecutors on the team, Carey Dunne and Mark Pomerantz, to quit in protest in February, citing Bragg’s reluctance in their letters of resignation. And several sources have told The Daily Beast that a lead prosecutor on the team, Solomon Shinerock, has become less involved in the investigation.

Under mounting pressure, Bragg felt it was wise last week to put out a statement assuring that “the investigation continues” and pledging to “publicly state the conclusion of our investigation—whether we conclude our work without bringing charges, or move forward with an indictment.”

It is not clear, however, if Trump’s lawyers are preparing for a clock-stopping measure, potentially from prosecutors hoping that their desire to criminally charge the twice-impeached ex-president outlasts Bragg’s tenure.

Five Trump advisers, including former and current attorneys, told The Daily Beast this week that they were not aware of this obscure New York law, with several asking questions such as, “How is that legal?”

For more than a year now, Trump himself has been privately telling close associates he expects his enemies to be investigating or suing him “for the rest of my life,” according to three people who’ve heard him use this same phrase, including as recently as early this year.

“He tells this joke that he’s making his lawyers’ boat payments, because of how he’s the ‘most investigated’ person in the world,” one of these people recalled.

New York isn’t the only state with this kind of intermission, which is called “tolling.” Florida gives law enforcement an extra three years if a defendant is “continuously absent from the state.” In Georgia, the statute of limitations in civil cases can be paused indefinitely until someone returns.

And there is an established history of how this has been used in New York. In 2019, a state court judge refused to toss out charges against a physician, Ricardo Cruciani, who faced accusations of drugging and raping his New York City patients in 2013. The judge noted the doctor had spent most of the next few years in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Bragg’s prosecutors have limited time though, no matter how you look at it.

After already indicting the Trump Organization and then-chief financial officer Allen Weisselberg last summer, prosecutors convened a new grand jury in the fall for a fresh round of indictments. But that grand jury’s term expires at the end of this month.

Prosecutors could seek to extend that, or scrap it and start all over again with another pool of jurors. But they almost certainly would then face accusations that they were jury-shopping and gaming the judicial system. Plus, the DA’s office would have to bring back its witnesses and hope they don’t change their story in a way that casts doubt on their testimony, several former prosecutors told The Daily Beast.

Former prosecutors also noted that using this clever time-out on the state’s statute of limitations gives investigators the ability to track down more witnesses, review additional documents, and apply more pressure to flip Trump Organization employees against their boss. And that, in turn, could help them convince their own boss to approve an indictment against Trump.

What’s still unclear is how far back prosecutors can reach.

If Manhattan prosecutors eventually hit Trump with the expected charge of falsifying business records, this legal pause button allows them to dig back at any financial documents he signed back in 2012. But if investigators pursue the rare criminal charge of enterprise corruption they get an extra five years that allows them to dig even further back—to 2007, according to a former prosecutor familiar with the law, who asked to remain anonymous because of their potential connections to the Trump case.

Then there’s the matter of when a crime actually occurred.

Unlike violent felonies that may have occurred at a specific time and place, financial crimes are understood as continuing transgressions that keep happening—especially if false documents are later relied upon to acquire bank loans or tax breaks. For example, one former prosecutor pointed out, investigators could argue the 2016 tax break Trump got by ballooning the value of his forested Seven Springs estate north of New York City relied on documents he approved years earlier.

As is already evident in the Manhattan DA’s current case against Weisselberg and the Trump Organization, prosecutors are operating on the theory that these financial crimes continued to occur for years. In that indictment, investigators cited a criminal conspiracy that allegedly ran from March 31, 2005, until June 30, 2021, the day before he was charged.

The New York County prosecutors working on the Trump investigation are in a unique position, having started their effort in the wake of the Justice Department’s failure to do so.

The federal prosecutor Trump himself appointed to the Southern District of New York, which oversees criminal matters in Manhattan, did not indict the president who placed him there. He probably couldn’t even if he wanted to; the Department of Justice continues to abide by an internal memo that prohibits pursuing a case against a sitting president.

The team of local prosecutors created by the previous district attorney, Cy Vance Jr., pursued the investigation of Trump even as they knew that he was effectively beyond their reach while remaining in the White House. In fact, that’s one reason that Kaufmann teamed up with two other lawyers a few years ago to draft an amendment to New York law in an attempt to freeze the statute of limitations if a person (like Trump) remained shielded by virtue of their official position, he told The Daily Beast. The effort ultimately went nowhere, but New York’s time-extending provision essentially does the same thing.

Still, even if prosecutors technically could go after Trump years from now, that possibility might be unlikely. If Bragg ultimately chooses not to indict Trump, four former prosecutors discussing the matter with The Daily Beast laughed at the idea that a new DA would pursue charges.

“It’s hard to think that a new prosecutor would blow the dust off of something and start up a whole investigation when this has been going on for years, assuming a decision not to prosecute is Bragg’s final word on it,” Kaufmann said.