ROME—Make no mistake, the Refugee Olympic Team, made up of displaced athletes, is no sympathy play. The 10 members, introduced by International Olympic Committee (IOC) Chairman Thomas Bach on Friday, are all Olympic-caliber athletes who have qualified to compete, and who happen to be refugees.

“They have no home, they have no team, they have no flag, and they have no national anthem,” Bach said as he introduced them. “We will offer them a home in the Olympic Village together with all the athletes of the world. The Olympic anthem will be played in their honor and the Olympic flag will lead them into the stadium.”

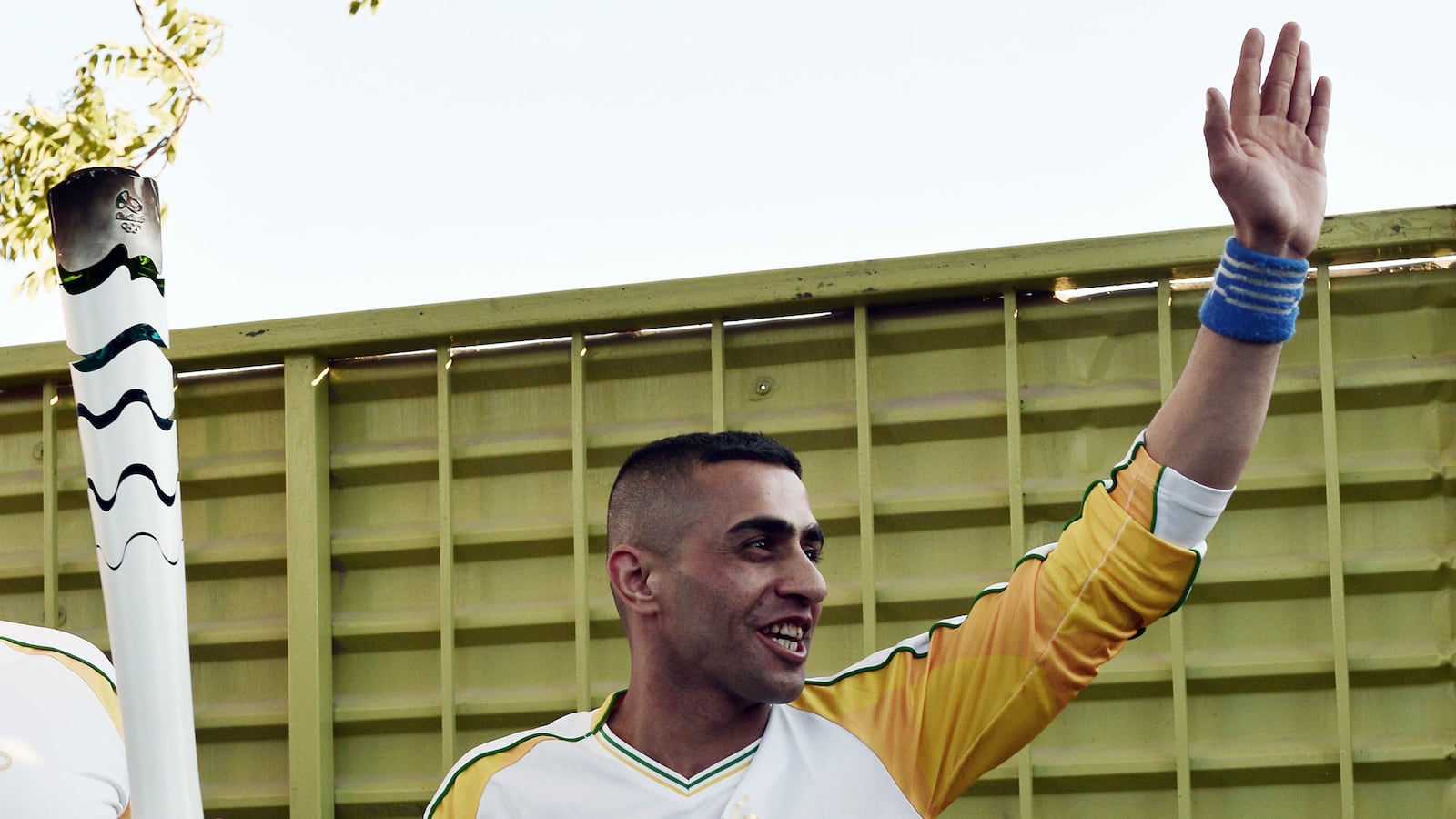

The refugee team will parade into the Olympic stadium welcoming ceremony ahead of host team Brazil, making them unarguably the most visible athletes to attend the event and, with luck, calling mass attention to the burgeoning global refugee crisis. They will be accompanied by 15 officials who will act as their coaches, technicians and trainers.

The refugee team members were chosen from a short list of 43 athletes who were identified as standouts in the Dadaab and Kakuma refugee camps in Africa, as well as from shelters in Europe.

Five are from South Sudan, two from Syria had found shelter in Europe, two are from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and asked for political asylum in Brazil, and one from Ethiopia was also in a refugee camp in Kenya, according to the official roster released by the IOC.

Many of the refugee team athletes already hold national titles in their former home countries. All are professionally on a par with those they will compete against in August when the Olympics kick off in Brazil, says Bach.

A spokesperson for the IOC told The Daily Beast that each candidate had to qualify under the same set of standards as all Olympic athletes face. “There were no shortcuts,” he said. “Each Refugee Olympic Team member earned the position.”

Some of the athletes have already made headlines, like Syrian Yusra Mardini, who was a competitive swimmer in Damascus before she and her sister fled to Beirut, then to Istanbul and later Izmir, Turkey where they paid a trafficker to take them along with 20 other passengers to the Greek island of Lesbos in 2015.

Less than an hour into the journey, their rubber dinghy started to sink and Mardini and her sister swam the rest of the way—nearly four hours—pulling the dinghy filled with remaining passengers behind them. “I thought it would be a real shame if I drowned at sea because I am a swimmer,” Mardini said at a press conference when she made it to Germany, where she was granted political asylum.

Mardini was among the first to express interest in competing in the Rio Olympics, but the Germans couldn’t put her on their team, and the Syrian government certainly wasn’t sending anyone who’d fled the war-torn nation. Up to now, it’s not clear that Syria will field a national team at all.

Mardini and fellow Syrian swimmer Rami Anis, a world champion in his own right, are the only non-Africans on the team. Before qualifying, Mardini said allowing refugees to compete despite their countryless status would send a message to the world. “I want to make all the refugees proud of me. It would show that even if we had a tough journey, we can achieve something.”

The team’s five South Sudan runners, including female team members Angelina Nada Lohalith and Rose Natike Lokonyen, and male team members Yiech Pur Biel, James Nyang Chiengjiek and Paolo Amotun Lokor, had all dreamed of running for the South Sudan team, but the country’s independence was not recognized in time for the Rio Olympics. The geopolitical and economic situation in Sudan and South Sudan, which claimed its independence in 2011, has meant that 1.7 million people are currently displaced and looking for a better life. The five Olympic athletes are all recognized by the United Nations as refugees whose status has been vetted.

“It is a very good opportunity for us,” Ndai Lohalith, said during training for the tryouts. “I will feel so proud to be there and to be recognized as a South Sudanese.”

Popole Misenga and Yolanda Mabika, both Judoka (judo practitioners) from the Democratic Republic of Congo, applied for political asylum in Brazil three years ago during the 2013 World Judo championships in Rio. Misenga ++told CNN++[[ ]] that he has no idea what has happened to the family he left behind, and he hopes that if they see him competing in the Olympics they will reach out to him—if they are still alive.