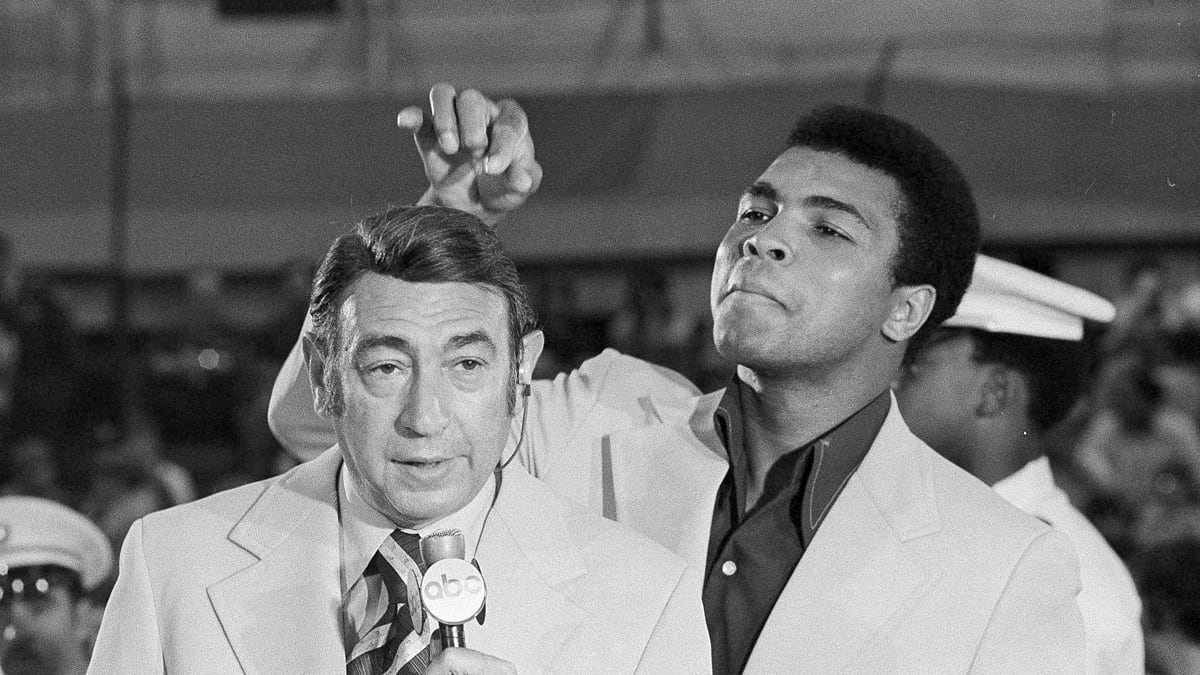

Howard Cosell once said to me, “Bobbin, you have a face for radio and a voice for print.” It was inspirational! Despite a bad toupee and the most irritating voice on the airwaves, this self-righteous stork was one of the main reasons why ABC was no longer the Almost Broadcasting Company, Monday Night Football the blockbuster hit of prime time, and a white sports audience came to understand Muhammad Ali’s persecution. One year, in the same poll, he was voted both the best-liked and most–hated sportscaster. Didn’t that mean he was the only sportscaster?

I didn’t always like Howard Cosell, but I did love him. He was encouraging to me, personally and by example; he used his radio and television pulpit to become the most important commentator on sports-related news in the country. Sure, he shilled for sporting events—football, boxing, baseball briefly, the Olympics, and some made-for-TV reality games—but he also delivered thundering jeremiads against greed, exploitation, racism, and the spurious use of tax dollars and eminent domain to build stadiums that would enrich the owners with whom he loved to mingle. Almost alone on the small screen, to this day, he was able to relate games to the surrounding culture.

Naively (he often accused me of being naive), I thought he would spawn a brave new generation of tell-it-like-it-is and tell-it-like-it-should-be broadcasters who would bring sports journalism at least up to the shaky standards of the rest of television news. But there was no Cosellian cohort. The industry barely had room for Keith Olbermann, his nearest kin in brilliance and insecurity. Cosell was not only sui generis, he also faded quickly from public consciousness once he was pushed off the air. All those mimics, on late night TV, street corners, and in bars went mute along with him. He was not celebrated. He had become inconvenient to the selling of processed sports.

ADVERTISEMENT

Finally, 16 years after his death, comes the first full-scale biography, Mark Ribowsky’s entertaining Howard Cosell: The Man, the Myth, and the Transformation of American Sports. By the end of its 512 pages of quotes and anecdotes, I felt almost as exhilarated and exhausted as after a long meal with Howard, the silver bullets (martinis) flying. Until the rigorous, scholarly biography appears, this one will do just fine. Ribowsky has stories to tell, even if he has no strong opinion or thesis to bind them.

Early on, Ribowsky calls his book “a modern fable, complete with shadings of Greek tragedy,” establishing it as overwrought as its subject. Ribowsky’s dubbing Cosell an “outlaw” who “transformed sports” doesn’t jibe with the more complex reality of a whining, starballing, stout-hearted constitutionalist who helped a hodge-podge of games become a major part of the American entertainment industry by standing on a ledge screaming for attention.

Cosell, a prude about porn and drugs, could be a pig around young women. He could be petty and mean-spirited to subordinates, ingratiating and sycophantic to bosses and celebrities. He drank too much and his limos stank of cigars. I stopped riding with him to events at which we both would appear, such as his Yale class, even if it meant two hours on a commuter train. Four months as a writer on his lame variety show, “Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell,” were hilarious and hellish. He could also be kindly, generous, fine company, and startlingly wise.

His magazine show, Sportsbeat, is still the standard of smart TV sports reporting—no wonder ABC let it die in the crannies of the schedule. Ribowsky’s coverage of the years Cosell defended Muhammad Ali’s right to his religious, political, and social opinions (while never endorsing them) is excellent, although Dave Kindred’s “Sound and Fury” recounts that key chapter of his life with more style and insight. (Also not to be forgotten are Cosell’s own four bombastic memoirs—I Never Played the Game, written with Peter Bonventre is the best—and several memoirs by television colleagues, generally unflattering to him. Last year, the University of Massachusetts Press published There You Have It, the historian John Bloom’s superb explication of Cosell’s Jewishness as the key to understanding how he juggled a passionate social conscience with an overweening ambition.)

Ribowsky is at his best making surprising connections from his heap of anecdotes and quotes. Years after David Halberstam was rejected as co-author of a Cosell autobiography, the late Pulitzer Prize winner would describe Cosell in a Playboy piece as one of those “joyless men and women who cannot love anyone but spend their lives desperately seeking admiration to counteract their feelings of inner emptiness.” Thank you, Dr. H. Ribowsky crowns his shrewd tracking of Cosell’s dependent relationship with Roone Arledge, the ABC executive who manipulated his career, with this quote from Arledge’s memoir: “Offer Howard national television time, he’d have good words for Pick-Up Sticks.” What better way to exemplify the puppet master’s contempt of what he considers his creation—and perhaps of himself?

Not that Cosell didn’t pull strings, too. People were “collectibles” to Cosell, according to Ribowsky. He could be a “con man” lying about or at least exaggerating his accomplishments. His motivations were suspect. When he quit broadcasting boxing in 1982, he was as piqued at not being given a news anchor job as he was disgusted by the brutality of the sport that had been one of his signatures. His rage at the “jockocracy”—the ex-players who broadcast the game—was as much fueled by their seemingly easy slide through life as their lack of journalistic chops.

Cosell was done in, I think, by his arrogance; he believed that his contributions to our enlightenment justified any lapses in sensitivity and his popularity shielded him from the long knives of the network suits, who by the eighties were tired of paying him and dealing with his tantrums. He was wrong. His contributions were immense and his popularity was real, but he was no longer needed. The mission had been accomplished—the games had been pimped.

His off-the-cuff Monday Night Football description of an African-American running back as “a little monkey” was all the suits needed to leave him out to wither and die. Forget that he had used the phrase previously on air to describe a white player. Forget that he was the acknowledged champion of Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith, and John Carlos, as well as dozens of black civil-rights activists who spoke up for him. Howard was no racist. But he had a big, loose mouth. And he was dangerous, the only broadcaster with the power to lure viewers into the tent with visions of jockamamie delights and then harangue them for not knowing what was really happening on the field and in the boardroom. He even had the chutzpah to declare “You can’t always be right and popular at the same time,” as if he were the last honest voice in the arena.

Maybe he was.