As it was for John, Independence was on Abigail’s mind that spring of 1776. In fact, she wrote to him, after recovering from a bout of “Jaundice, Rhumatism and a most violent cold,” the residual effects of dysentery, she thought, to inquire about the status of political alliance. “I wish I knew what mighty things were fabricating,” and she asked; “If a form of Government is to be established here what one will be assumed? Will it be left to our assemblies to chuse one? And will not many men have many minds? And shall we not run into Dissentions among ourselves?”

Abigail, since the outbreak of fighting and the danger that hostilities had brought to her neighborhood… had developed an independent stance on politics.

By this time, Abigail was not reticent about politics. She asked the central questions that prevailed in the halls of Congress. From her conversations with John, she knew that many shades of opinion existed among the delegates. Moreover, from reading history and experiencing events around her, she had formulated strong opinions about politics as well as politicians.

A daughter of New England with its Puritan cast of mind, with its suspicions and its skepticism, and from her experiences of the long year past, Abigail had become pessimistic. Her distrust of human behavior became greater even than John’s. He believed that with the proper education, people and institutions could be perfected. Abigail’s mood was otherwise when she wrote her thoughts to John about what kind of government should be created for the new nation.

Perhaps Abigail’s skepticism developed because she had none of the stimulation of laboring in the halls of Congress. There, despite all his grave frustrations and irritations, John was daily motivated by grand ideals and experienced the exhilaration of influence and power. Abigail’s daily sensations included fear, fatigue, and grief. John’s challenges focused on declaring independence, establishing government, and executing a war. Hers included coping with invasions, illness, and farmhands. Their immediate worlds, his in Congress, hers in Braintree, had different orbits. So Abigail continued her gloomy late-night reflections about the prospective government: “I am more and more convinced that Man is a dangerous creature,” she began,

and that power whether vested in many or a few is ever grasping, and like the grave cries give, give. The great fish swallow up the small, and he who is most strenuous for the Rights of the people, when vested with power, is as eager after the prerogatives of Government.

She continued her late-night “conversation” with John by correspondence, the form in which they communicated. “You tell me of degrees of perfection to which Human Nature is capable of arriving, and I believe it, but at the same time lament that our admiration should arise from scarcity of the instances.” Abigail, since the outbreak of fighting and the danger that hostilities had brought to her neighborhood, and especially since her ordeal in the dysentery epidemic, had developed an independent stance on politics. She observed, for instance, that people had grown accustomed to a lack of formal government since the restraints of Great Britain had been “slakned,” and she queried John:

If we separate from Britain, what Code of Laws will be established? How shall we be governed so as to retain our Liberties? Can any government be free which is not administered by general stated Laws? Who shall frame these Laws? Who will give them force and energy?...I feel anxious for the fate of our Monarchy or Democracy or what ever is to take place. I soon get lost in a Labryinth of perplexities.

The labyrinth of perplexities that Abigail surveyed best summarized the vexations of the delegates in Philadelphia. She fully comprehended the complexity of state formation faced by nation in rebellion, that it was not just ideology that governed people’s behavior, but passions and self-interest. Writing at night, after her family slept and the house was quiet; she had the privacy to formulate her thoughts. And once more, she sealed and mailed them to her husband, who wondered about these same issues.

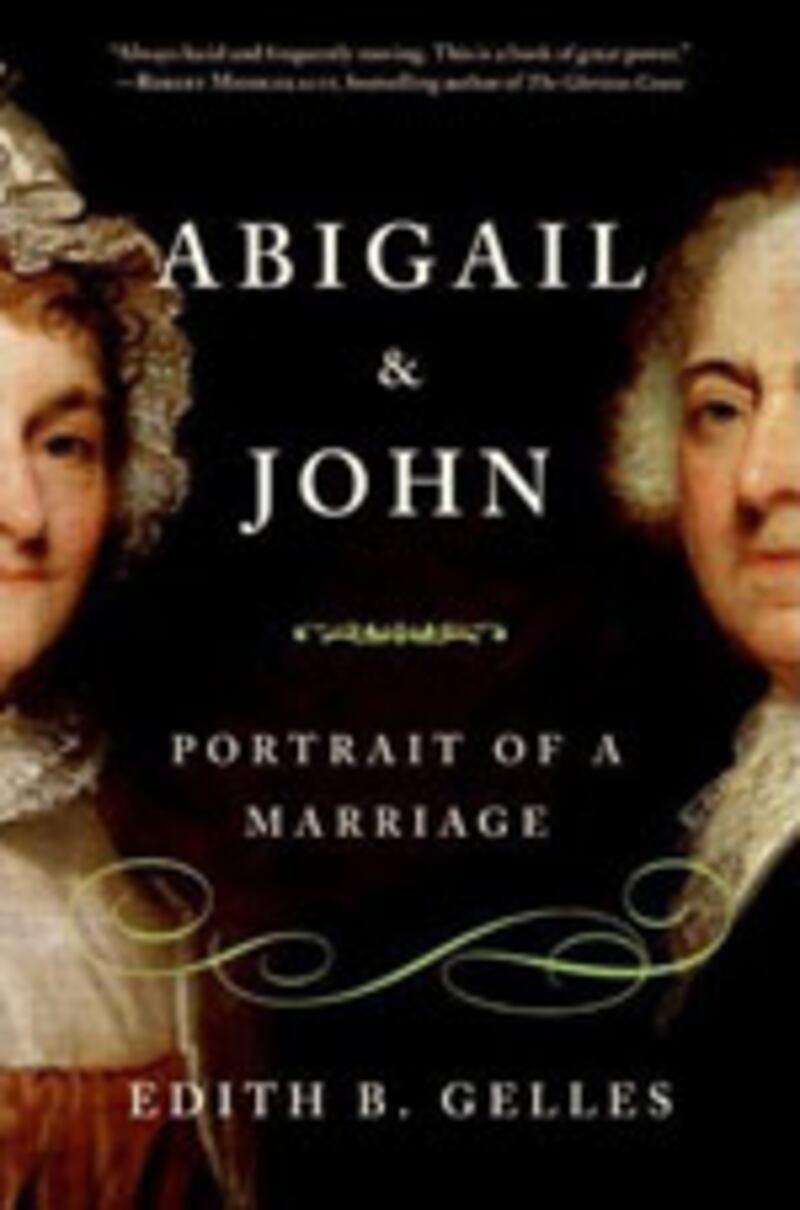

Excerpted from Abigail & John: Portrait of a Marriage by Edith Gelles © 2009. With permission from the publisher, William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins.

Dr. Edith Gelles began her research into the Adamses over 30 years ago and is the author of two books about Abigail for the academic market: Portia: The World of Abigail Adams, a co-winner of the American Historical Association’s Herbert Feis Award, and Abigail Adams: A Writing Life, an examination of Abigail’s life through her letters. She lives in Palo Alto, California.