There was only one member of the Yeats family to win an Olympic medal for art—and it was not William Butler.

In Sandymount, Ireland, 150 years ago this year, one of the greatest poets of the 20th century was born. To mark the birth of William Butler Yeats, essays, exhibitions, and books are surely being planned all over the English-speaking world. But for those 150 years, the poet and dramatist’s long shadow has kept one of Ireland’s most talented painters in the dark—his own brother, Jack Yeats.

Any visitor to Dublin who takes time off from devouring scones or tippling the wares at the Jameson Distillery and Guinness Storehouse, and who instead steps into the National Gallery of Ireland, is in for a real treat. While its collection of French, Spanish, Italian, Flemish, and Dutch paintings is respectable, visitors are sure to find themselves utterly riveted by its collection of paintings by Jack Yeats.

Jack Butler Yeats was born in London on August 29, 1871, to a long-suffering Anglo-Irish Protestant family. His father was the painter John Butler Yeats; his mother, Susan Pollexfen, suffered from depression and went mad. His siblings included not only his famous brother, but two sisters, Lily and Elizabeth, who also became known for their careers in embroidery and publishing, respectively. While Jack was largely silent on what he thought of his father’s work, he told the BBC in 1948 that he painted because he was the son of a painter.

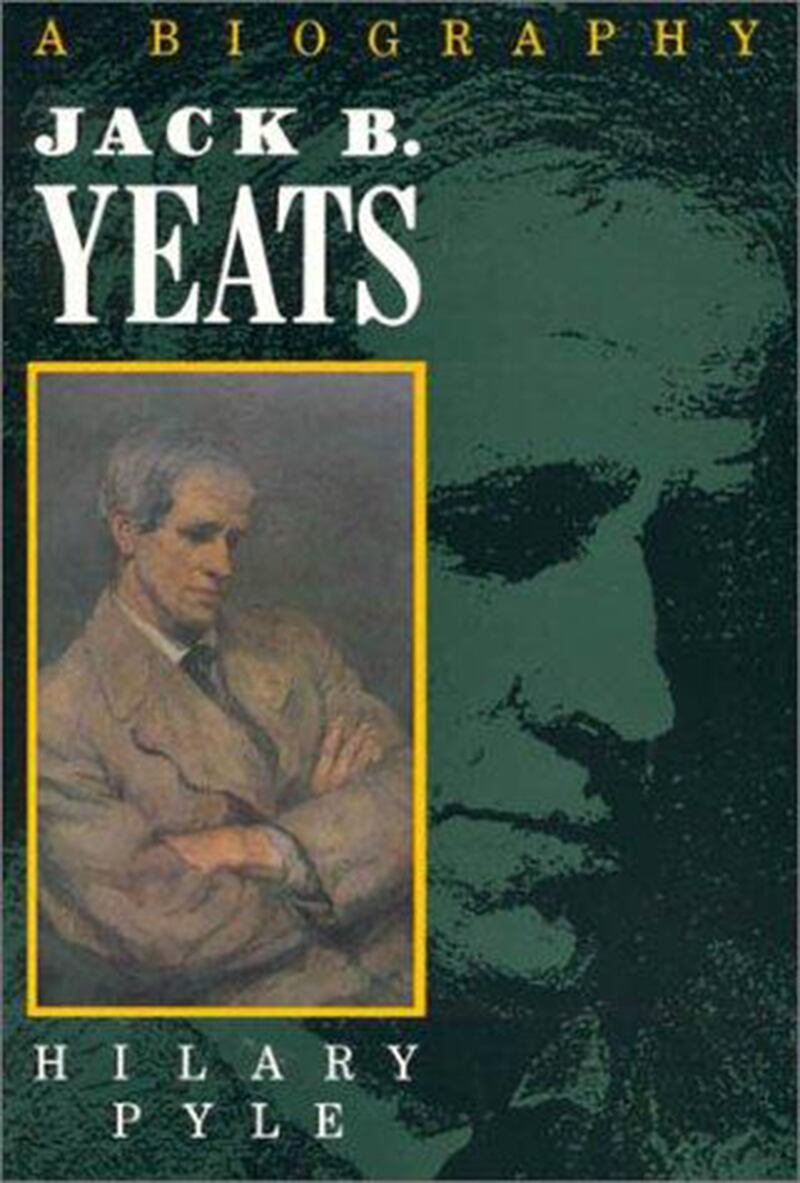

Jack spent his formative years with his maternal grandparents in Sligo, a coastal seaport in western Ireland. As Hilary Pyle notes in her seminal work on the painter, Jack B. Yeats: A Biography, Jack’s time there was largely a boon, as he escaped the family drama in London in which his older brother and sisters grew up. Without drawing too direct of a conclusion, the outcome of that separation seems to be an air of independence in Jack’s life and career. He would also become a very different man from his famous brother—with whom he was not close—as Jack was by all accounts a faithful husband and consistent churchgoer, content, and private.

“When he started out in his career, he trained as an illustrator,” says Angela Griffith, a professor of art history at Trinity College in Dublin. Yeats worked for multiple illustrated magazines and newspapers in London, including Punch. In that role, he covered horse races, boxing matches, and events including Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show when it came to London. “He had a wide range of interest as an illustrator, he did whatever he was asked to do,” Griffith says.

In 1905, Yates joined the playwright John Millington Synge on a tour of western Ireland for the Manchester Guardian (now The Guardian), to capture life in the part of Ireland that was still seen as “authentic” and untouched by the British and modernity. Synge would later face stinging criticism from Irish nationalists—a well as riots—over the play that was inspired by this region, The Playboy of the Western World. In 1910, Yeats would move back to Ireland with his wife. While working as an illustrator, Yeats began his self-taught career as a painter.

His early paintings reflect his training as an illustrator with meticulously drawn subjects, filled-in color, and noticeable outlines. A good example of the sort of work he did was his 1915 painting “Before the Start,” in which the eye of the illustrator can certainly be seen. Yeats’s early success is perhaps best represented by the fact that he was included as one of the European artists represented in the 1913 Armory Show.

While Yeats would evolve as a painter—his career is seen as generally having three phases—his subjects throughout would often be drawn from the fringes of Irish society, and he was an astute chronicler of the world as he experienced it.

“He was one among the first artists to explore and represent the character of ordinary Irish people in a way that challenged the stereotypes of ignorant and simianized peasants popularized in the press during the 19th century,” Yvonne Scott, the director of the Irish Art Research Centre, points out. “He was empathetic to the peripatetic outsiders—the tinkers (as they were then called), travellers, circus folk, emigrants, hobos.”

His second phase as an artist, beginning in the 1920s, is probably best captured by 1923’s “The Liffey Swim” —which won him the Olympic medal. This period saw him become more fluid as a painter, with expressionist influences and visibly broad brushstrokes.

As Yeats aged, he continued to evolve into what is generally considered his third phase, which saw him become more associated with Symbolism. “His titles become much more poetic, much more lyrical,” points out Griffith, and are metaphorical rather than “depicting events or people.” One of the more visually stimulating and emotionally dramatic paintings from this time is his iconic “Men of Destiny” from 1946. While Yeats never became an abstract painter, Yvonne Scott says that his work “over the next couple of decades [would] exceed all other painters in terms of freedom of handling, and dissolution of the painted surface in keeping with his increasingly abstracted subject matter—dealing with themes of grief, loss, displacement, searching, and so forth.”

“Men of Destiny,” and others like it, were left open to interpretation. It was up to the viewer to answer the question of whether Yeats was painting about the new Ireland, or immigration, or travel, or any other number of potential issues. “He never prescribed meanings, he never explained his paintings… He invited people to interpret them,” says Griffith.

Yeats also became the center of a high-stakes debate between two of Ireland’s brightest 20th-century artistic stars—Samuel Beckett and Thomas MacGreevy—over Irish art and its relationship to a new Irish identity.

Unlike his brother, Jack Yeats was an avowed supporter of Irish independence, and his paintings leave one with an overwhelming sense of their unique Irish-ness. As Karen Brown notes in her book, The Yeats Circle, Verbal and Visual Relations in Ireland, the poet MacGreevy, who would go on to become director of the National Gallery of Ireland, declared that Yeats was “the first genuine artist … who so identified himself with the people of Ireland as to be able to give true and good and beautiful expression to the life they lived, and to that sense of themselves as the Irish nation … his work was the consummate expression of the spirit of his own nation at one of the supreme points in it evolution.”

When he was writing the essay in which that quote appears, MacGreevy sent Beckett a draft, which gave rise to one of Beckett’s more famous ripostes about his “chronic inability to understand as member of any proposition a phrase like ‘the Irish people’ or to imagine that it ever gave fart in its corduroys for any form of art whatsoever, whether before the union or after, or that it was ever capable of any thought or act other than the rudimentary thoughts and acts belted into it by the priests and the demagogues in service of the priests.”

The Beckett camp wanted to place Yeats’s artwork in a more universal context, rather than tie it and the artist to Ireland and the Irish experience. “The national aspects of Mr. Yeats’s genius have, I think, been over-stated, and for motives not always remarkable for their aesthetic purity,” Beckett wrote for The Irish Times in 1945. “[Yeats] is with the great of our time, Kandinsky and Klee, Ballmer and Bram van Velde, Rouault and Braque, because he brings light, as only the great dare to bring light, to the issueless predicament of existence, reduces the dark where there might have been, mathematically at least, a door.”

Yeats was not without his critics. His vast body of work is not of a consistently high quality. Bruce Arnold points out that in 1924, one critic wrote that Yeats’s “painting is now and then so crude as to border on amateurishness,” while another pined for his work as an illustrator, declaring Yeats to be “far less happy with oils than with the simple medium of pen and ink.”

Nevertheless, it is clear that Yeats’s work was well received, and not just in Ireland. Yet aside from some wealthy patrons, who made his works some of the more lucrative on the art market —one sold for more than $2 million in 1999—Jack Yeats is a virtual unknown today for general audiences.

Part of this oversight stems from the reality that while many want his art to be viewed separately from his personal beliefs, the content of his paintings does come across as incredibly specific to the Irish experience. Another problem may be that Yeats requested that his paintings not be reproduced or photographed, as he believed you could never understand his work by looking at a reproduction. He also appears not to have left a significant legacy in terms of the Irish painters that came after him, as their concerns were more about being in conversation with what was happening in continental Europe as well as the U.S. And finally, unlike his brother, Jack was an intensely private individual and was not necessarily adept at the self-promotion required for long-lasting fame.

There is a silver lining. When you finally do find yourself lost in front of ”About to Write a Letter,” ”Morning in a City,” or ”Men of Destiny,” you will probably be able to enjoy it without a crowd.