World

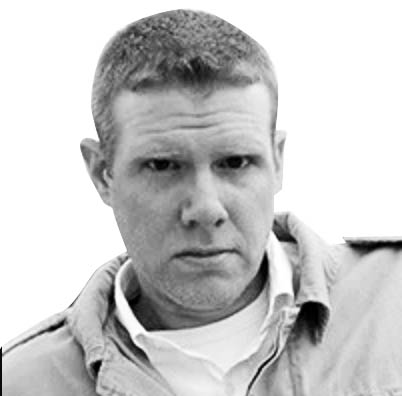

Marcos Brindicci

The Overthrow of Bolivia’s Evo Morales Takes Us Back to Latin America’s ‘Dirty Wars’

TRUMPED

A far-right coup in Bolivia—openly endorsed by the Trump administration—highlights the growing danger of increased militarization in Latin America.

Trending Now