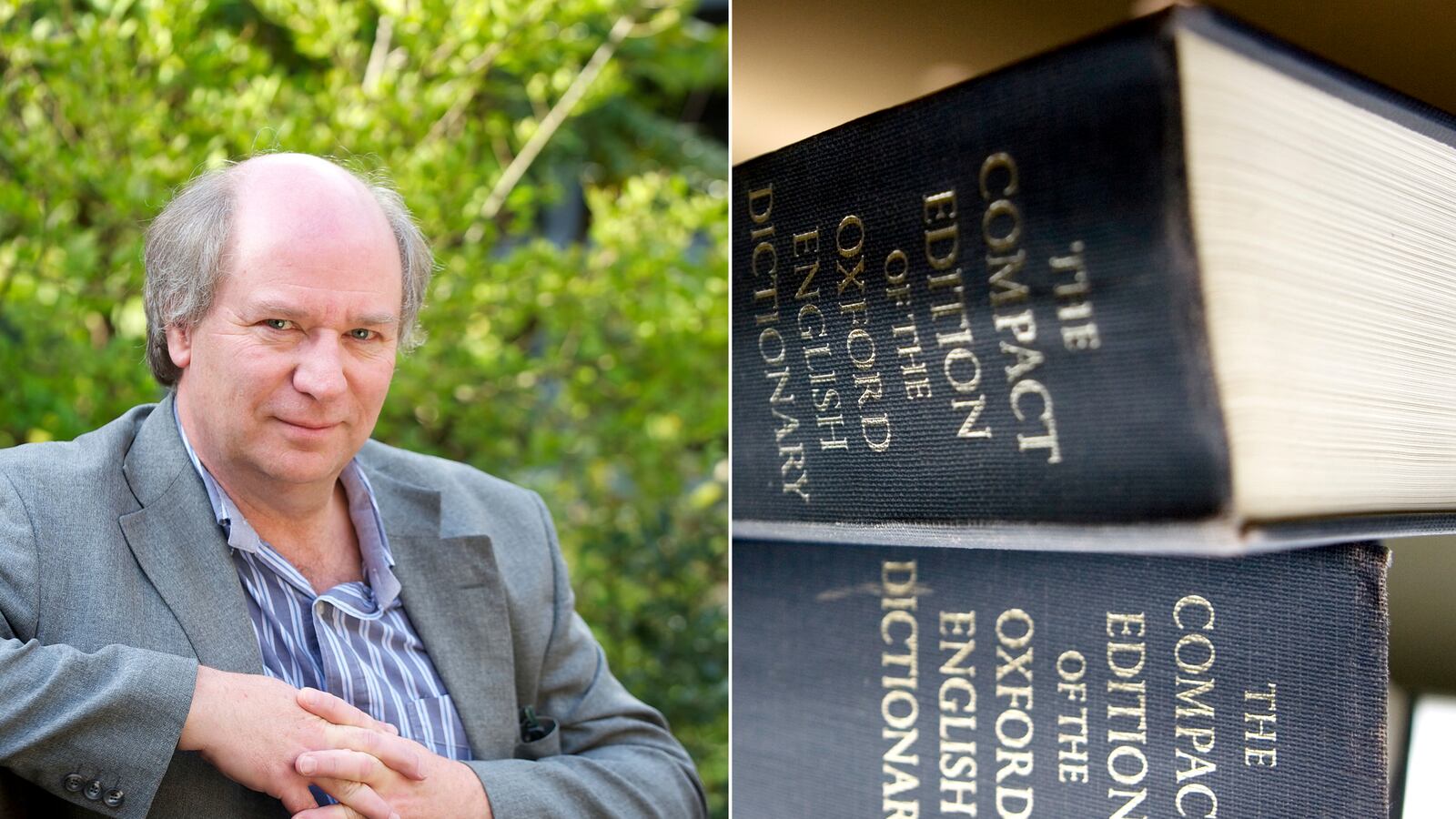

When it comes to the digital revolution, John Simpson, the soon-to-be-former editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, is the most sanguine man in book publishing I’ve ever talked to. A quick perusal of the dictionary’s history helps explain why. When the founding editors started the project, in 1858, they thought it would take 10 years. Instead, it took 70 years to sort through the quotations submitted by thousands of volunteer readers and publish a first edition. Almost immediately, OED had to be updated with additional volumes. It was a constant race against an evolving language, and taking decades to publish one edition makes it hard to keep up with words.

In 1993, Simpson oversaw the conversion to digital. More than 100 typists rewrote the whole 20-volume set, but it was all worth it.

“It’s so much more than just a single lookup mechanism like it was in the old days,” Simpson says. “It’s more of a voyage around the language.”

The Internet is the natural home for the OED, which is the original crowdsourced project, ever since it began in the mid 19th century. The mission was to record the oldest known usage of every English word that’s been around since the 12th century, the end of the Old English era. A massive project, it came to rely heavily on volunteer readers. Back then, they would write down examples of a word on an index card and mail it to the editors. Today, Google Books and other searchable text databases have been a godsend. The card files are still the first place Simpson looks when researching a word, but he’s the exception. “A lot of our work now isn’t so much reading text and looking for info about words but doing databases searches,” he says.

Digitization has also made updating the dictionary far easier. The OED is constantly being updated, and not just as new words are coined, but as volunteers alert the editors to earlier examples of known words. “We’re very aware that what we produce is a moving text,” Simpson says. “It’s not a headstone for the English language.”

Now, as Simpson prepares to leave after 37 years at the dictionary, he wonders whether the next edition will be printed at all.

The internet has brought changes to the dictionary’s content as well, with “words” like LOL, OMG, WTF, and the heart symbol making their way in. Sometimes the words have an older pedigree than you might expect. Simpson found that OMG easily dates back to the 1980s, and even has an outlying instance in a 1917 letter to Winston Churchill. “I hear that a new order of Knighthood is on the tapis,” the letter reads. “O.M.G. (Oh! My! God!)—Shower it on the Admiralty!!”

Simpson has presided over the inclusion of 60,000 new words and meanings to the dictionary, but he’s particularly interested in words that began in digital form, on Internet message boards, emails, or SMS texts. The dictionary started including words that had never been printed 10 years ago. “We have a sort of defense mechanism here in that we usually don’t put words directly into the dictionary,” Simpson says. “We usually wait six, seven, 10 years to see how a word will morph and change in the early years of being in the language, to see if it can survive.” “Flaming” was one of the first, meaning to inundate someone with email spam. Now it has a different meaning: to inundate someone with profanity and insults.

Of course there are those who bristle at such neologisms—the scolds, the conservative prescriptivists, the SNOOTs. But Simpson isn’t one of them. He says he’s fascinated by the way language drifts and mutates. “It’s just what happens in language, so it doesn’t worry me,” he says. “I don’t think we’ll start putting in ‘nucular’ instead of ‘nuclear,’ though we have material on both usages because it’s of academic and general interest.” He’s even calm in the face of metaphors turned idioms that are widely misused—like “break the mold” to mean something daring and different—rather than a creation that can’t be repeated. Or “beg the question,” to mean raising the question. (Biden is a frequent offender.) “I don’t go up to people and grab them by the collar and say you can’t use it this way; it’s just the way it evolves,” Simpson says.

“Evolution” is one of his favorites. It began as a term for soldiers or ships rotating in formation, before it got picked up by the natural sciences. “It was quite fun to work on that one,” he looks back fondly. “Any word has interesting facets in its history.”