Firefighters across the nation consult a go-to website for cautionary tales. The “Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center” shares things that have gone wrong so that next time everyone can hopefully avoid the pitfalls. Today, the site is brimming with the uncharted challenges of combating natural disasters during a pandemic.

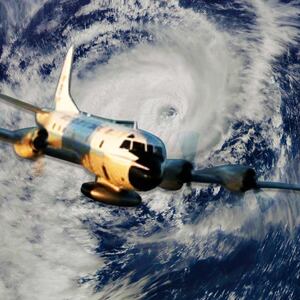

It’s hard enough to confront a blaze, or hurricane, or earthquake at the best of times. Weather forecasters expect a busy natural disaster season, following Hurricane Hanna’s debut last weekend. But the historic knowledge of how to cope no longer applies, and the Lessons Learned website’s posts paint a disturbing picture.

While fighting the Sawtooth inferno in Arizona in June, for instance, firefighters assumed they’d get help from the state’s Department of Health staffers in case someone contracted COVID-19. The department said it would not assist, however. The guidance for COVID-19 mitigation like social distancing was not clear or consistent, either.

ADVERTISEMENT

Then at the Murphy Fire in California that same month, a symptomatic crew member rode unmasked in a vehicle with two other men. People who had contact with him did not self-isolate afterwards. Supervisors elsewhere didn’t push men to wear masks. Firefighters who had been in contact with COVID-19-infected personnel were unable to get timely testing. Forms didn’t allow for virtual signatures for work assignments.

In other words, a mess.

“This guidance has been overwhelming in volume, differs by agency, and includes significant ambiguity,” wrote Jayson Coil, the assistant chief of the Sedona, Arizona fire district. “If we are going to take meaningful actions to minimize the spread of COVID-19 on incidents, we need to recognize the difficulty associated with changing long-held practices at this level.”

Since April, FEMA and emergency managers across the country have been working on modifying plans for hurricanes, floods, and earthquakes. But FEMA and Red Cross guidelines are just that. They indicate what to change but fall short of telling communities how to act. The calculus of each locale hinges on the severity of virus outbreaks, if resources have been diverted to the pandemic, and whether elected officials recognize the gravity of the situation.

Plus, many of the volunteers on whom emergency responders depend are over 60, and being high risk are reluctant to travel across the country and expose themselves to the disease. Back in May, Greg Forrester, the head of the National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters, forecast that numbers could plummet by half. And if an out-of-state contractor or volunteer falls ill, who’s responsible for their tests and medical care?

Aside from stretched resources and unclear directions from the government, there is the lack of rapid testing for both responders and evacuees that would aid planning for shelters and evacuation.

“Testing, testing, testing is what we keep stressing,” said Rob Dale, a weather emergency expert from Lansing, Michigan. “We need more of it and faster.”

Without it, sheltering evacuees presents unprecedented headaches during the coronavirus era. New social distancing requirements require reevaluating space availability, staffing, and how to isolate those who show symptoms.

But if you have a population with a high susceptibility, busing them to a school five miles inland might be unfeasible. Fleeing people often go to hotels or across state lines to stay with family. But hotels may be closed or have limited staff. And going from a high transmission zone to a lesser one can cause potential conflicts in the host community. Requiring a 14-day quarantine is not enforceable. Evacuation is also an expensive endeavor, and people who have lost jobs may not be able to afford an extended hotel stay.

Besides, many public libraries and schools that normally host evacuees are closed. Sheltering might now involve allotting 60 square feet to a pod instead of 20, which raises the question of where to put the spillover.

“It’s easy to say you need to open three rather than one shelter to spread out,” says Samantha Montano, an assistant professor of emergency management at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. “But do you have those buildings? Will you have enough people to staff them?”

Montano wonders whether public outreach regarding revised evacuation strategies is getting through. If you’ve lived in places like New Orleans that endure frequent hurricanes, you probably have a time-honored plan, your trusted source of news, and a sense of what to grab if evacuating. That no longer holds. While New Orleans updated its preparedness website to address pandemic considerations, it’s unclear how many residents have actually looked at it.

(Note to readers: if you have any doubt about evacuation plans or centers, contact the local fire department. If they don’t have the answers, they’ll know where to turn.)

By and large, emergency responders emphasize that people should not delay in seeking help because of the virus. Taking refuge in a safe place is preferable than riding out disasters in dangerous conditions.

The Guardian quoted Henry Van De Putte, chief executive of the Red Cross’ Texas Gulf Coast chapter, as saying that the organization would open more shelters with reduced capacity to ensure social distancing in response to Hanna. Volunteers and people seeking refuge underwent temperature checks, and medical professionals were assigned to each location.

“Yes, coronavirus provides risk but so does floodwater, so does not having electricity, so does not having required medications,” Van De Putte said. “We’re doing everything we can do possible to make it a safe environment.”

Typically, as a community plans for a disaster, it often builds in the ability to receive help from neighboring jurisdictions and states. When an entire country is dealing with an event such as a pandemic, the availability of those trained and qualified becomes much more limited or even non-existent, says Brad Gilbert, the director of the Union County Emergency Management Agency in Ohio.

“Many programs are understaffed and are unable to meet the challenges of any disaster alone,” he says.

As such, communities need to be even more self-sufficient should disaster strike. This makes preparedness beforehand even more important as well as a long-term response plan at the ready. Districts, businesses, hospitals, and others need to expand their depth of trained staff to fill multiple roles when an emergency occurs. It also brings to the fore the need to make more funding available on the local, state, and federal level for emergency management programs.

But even if locales can get help from other states, volunteers could bring the virus with them. That’s particularly risky with wildfires, where crews from several states often converge to fight big blazes. If a firefighter gets an assignment, he just goes, and that means someone flying in from a high transmission state could be unwittingly carrying the germ.

For the most part, testing only occurs once someone presents symptoms, and by then others in the team may have been infected, says Jim Whittington, a wildland fire expert based in Oregon.

Crews work in close quarters, and shower and sleep in proximity, which makes social distancing nigh impossible. Managers are trying to keep crew units apart from each other, but that’s hard to do in large operation drawing hundreds of men from around the country.

Then there’s the politics of mask-wearing.

“At the start they were seeing resistance to wearing masks when not on the fire line, especially in states like Arizona where the state leadership doesn’t model this behavior,” says Whittington. “Some of these happened when the state government was basically not acknowledging there was a pandemic.”

Whittington’s worst-case scenario involves 40 percent fewer available firefighters, or a large-scale fire which carries a massive transmission. His best case is that protocols and actions will improve over time as emergency responders absorb the lessons learned.

“So far it’s not looking great,” he says. “Hopefully by the end of the year, we’ll be a lot better at thinking these things through.”

Judith Matloff teaches crisis reporting at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. She is author of the newly published How to Drag a Body and Other Safety Tips You Hope to Never Need.