Brazil is on fire, with hundreds of thousands of people hitting the streets to vent their anger and rage at corruption, the high cost of living, and proposed hikes in bus fares. Protests in Istanbul are still raging after nearly a month. Even Stockholm was raging in the recent weeks.

Welcome to the first truly urban century. It’s not going to be pretty. Reasons for these protests are nearly impossible to define, even on a superficial level, but one through line is clear—these are cases of city dwellers being plain fed up.

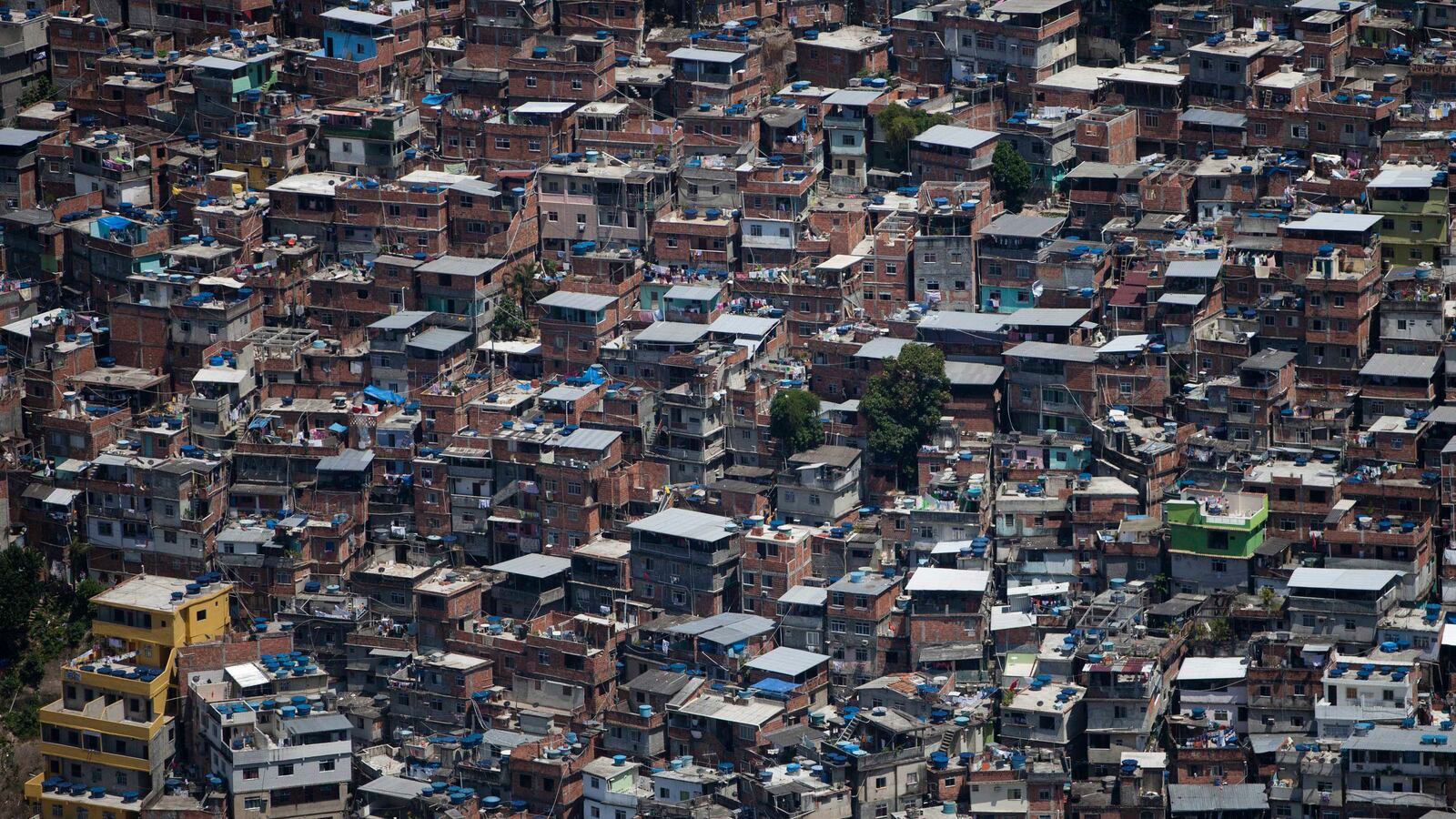

In Brazil, bus fares and corruption were only superficial catalysts for the rage in the streets. The underlying cause is an urban nation that is split neatly between the haves and have-nots. In economic lingo, Brazil is one of the BRIC countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China—a block of nations with rapidly advancing economies. But while the wealthy flaunt their excessive lifestyles in Rio and São Paulo, life in the favelas, or shantytowns, is murderously hard.

The favelas, founded by soldiers with nowhere else to go, have been around for hundreds of years. By the 1970s, as urbanization became a lifeline for impoverished Brazilians looking for work, they became breeding grounds for violent gangs, drug dealers, and dirty politics. The most realistic portrayal of life in the favela was Fernando Meirelles’s extraordinarily graphic and disturbing 2002 film City of God. In it, Meirelles exposes the horrors of poverty—all while golden riches lay a few miles away.

In one horrific and memorable scene, a child of about 9 shoots a child of about 3 in the foot as a rite of initiation into a gang. The wounded child’s screams of agony are unbearable, as was most of the film, which naturally ruffled the feathers of Brazil’s elite.

Now the inhabitants of these urban sprawls, along with the young and the angry, are rising up to make their case heard. The initial causes of the protests almost seem lost in the violence and immediacy of the clashes. When people have had enough, they have had enough. Or as one Brazilian commenter said on the BBC Radio Four program, “The genie is out of the bottle.”

It’s ironic that the first clashes began in São Paulo two weeks ago, because just a week before, a conference was held in that city, with great success, sponsored by the New Cities Foundation, a Geneva-based NGO.

The foundation’s mandate is to promote sustainable, dynamic dialogue in cities and to seek ways to make cities user-friendlier for the masses. The conference brought together mayors and thought leaders from all over the world. São Paulo’s beleaguered 50-year-old center-left mayor, Fernando Haddad, was one of the stars of the show. After the conference, he flew triumphantly to Paris, where he was feted at dinners and parties, to try to gather interest for São Paulo’s bid to host the World Expo in 2020. Then the news broke of the first protests. Haddad flew back immediately to find his city rising up, and is now beating a hasty retreat on the bus-fare increase. But it’s almost too late.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the protests in Istanbul, a city of 20 million people, are still going strong. This is despite the tear gas, the beatings, and the threats the protesters have faced—as well as a new-age German musician who set up a grand piano in the middle of Taksim Square, in an attempt to quell the rioters’ nerves.

Similar to what’s happening in Brazil, in Turkey the protesters began their uprising to fight the urban sprawl that they saw as destroying their city, but also as a cry against the increasing Islamic agenda they see as a threat to secular society.

Istanbul, São Paulo, Stockholm, Ankara, Rio—and let’s not forget the Arab Spring, which started in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, when a vegetable seller ignited himself in flames after finding no way to beat the poverty cycle. That movement spread to Tunis, Cairo, Benghazi, and Daraa, and later Damascus and Aleppo. Will London, Paris, and New York be next?

Is there a link to the cities rising up? With more and more people flocking to urban life, is there a way we can look to the future to make our cities more habitable?

John Rossant, the chairman and founder of New Cities Foundation, which convened the São Paulo conference, claims that these uprisings, as well as the Arab Spring awakenings, are linked. Lessons must be learned from the past if we wish to live harmoniously, especially as populations explode and more of us become city dwellers.

Rossant notes that more than half the Chinese population is now urban—from barely 20 percent one generation ago—and another quarter-billion Chinese are expected to move into cities over the next 12 years. India’s cities are also booming. Indonesia, the fourth-most-populated country in the world, is undergoing vast changes since the economic recession as poor people flock to cities looking for work.

But overcrowded and ill-organized cities are breeding grounds for discontent. London keeps growing and swallowing up more expanses of wasteland, such as Docklands, which was turned into a Disneyland for last year’s Olympics held there. Despite the leadership of a charismatic and attractive mayor—Boris Johnson, who may or may not be the next prime minister—working people are angry at the stifling charges simply to drive a car inside the city center.

In Paris, where I live, the inner neighborhoods are only available to the white elite. The poor and dispossessed are shuffled out to suburbs and never seen. When they revolt to express their rage, as they did in the autumn of 2004, Parisians act baffled as to why they are complaining. The socioeconomic gap at times seems too enormous to grasp.

Manhattan is increasingly less available to average-income earners. Occupy Wall Street was a disorganized movement without a clear focus and power base—essential in any successful revolution—but the message was clear: the divisions between those who are fortunate enough to enjoy city living as opposed to those who find it unbearable are too wide.

So how do we find a way to live harmoniously in urban settings? Rossant and many others believe that the Brazil riots are just the start of many. What’s important, he notes, is that politics in this first truly urban century will largely take place in cities and will largely be about cities. And we must pay attention.

So what can mayors, politicians, leaders do? Listen to their people. “They need to stimulate the senses and the spirit as well as providing jobs,” says Rossant. “They must learn to respect the dignity and fundamental equality of their residents.”

Easier said than done, of course. But listening is always a good start.