Obama will appoint a liberal to replace John Paul Stevens, but Adam Winkler says only one has his potential as a coalition-builder.

Justice John Paul Stevens’ retirement announcement is but a few days old and it’s already become conventional wisdom that whomever President Barack Obama chooses to succeed him, the balance on the Supreme Court won’t change. Stevens is on the liberal wing of the court and presumably Obama will choose someone of similar disposition. But there is more to a Supreme Court justice than how he votes—and liberals may find that Stevens’ successor can’t do nearly as much to further their causes. The number of liberals and conservatives on the court may stay the same, but the outcomes of cases may veer to the right.

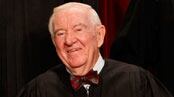

Stevens, once called “a wily practitioner of coalition politics,” worked the hallways to get votes.

ADVERTISEMENT

The late Justice William Brennan used to ask his new law clerks what the most important rule in constitutional law was. They would ponder the question and respond, “freedom of speech,” “separation church and state,” or “separation of powers.” No, Brennan would respond with a wry smile. And then he would hold out one hand with his fingers outstretched. “Five,” he would say. A justice needs five votes to make a majority on the nine-member court. With five votes, a justice could do anything.

No one understood Brennan’s five-fingers rule better than Stevens. He knew that majorities on the court are precious and fragile. There was an art to making sure that the majority held, that no justice wavered. Over the past two decades on the closely divided court, gaining five votes usually meant appealing to swing justices like Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy. So Stevens did whatever he could to keep those justices on his side.

In many cases, that meant assigning O’Connor or Kennedy to write the majority opinion in controversial cases. In the Supreme Court, the choice over who writes a majority opinion belongs to the chief justice if he’s in the majority. When the chief justice is in the minority, however, the authority to assign the opinion falls to the most senior justice in the majority. For the last 16 years, that person was most often Stevens.

To keep O’Connor or Kennedy on board, Stevens would strategically give them pride of authorship. If Stevens kept the opinion for himself or assigned it to one of the more liberal justices, there was the chance that O’Connor or Kennedy would find something in it they didn’t like. Justices vote on a case after oral argument is heard but they can change their minds any time in the months it takes to issue a final, publishable opinion. O’Connor and Kennedy, if they thought an opinion was going too far, were always a threat to defect from the majority and write for themselves—undermining the precedential effect of the case—or worse, join the dissenters and give them a majority.

Kennedy was known to waver. In a landmark abortion case from 1992, Kennedy initially voted to overturn Roe v. Wade, the decision that first recognized women’s right to choose to have an abortion. But Kennedy had second thoughts and opened up conversations with the dissenting justices. Eventually he was persuaded to change his vote. Roe was affirmed and, to this day, women still have the right to determine for themselves whether they will become mothers.

Stevens’ diplomatic use of opinion assignment was illustrated in the court’s 2003 landmark decision affirming the constitutionality of affirmative action in higher education. Justice O’Connor, the swing vote, initially sided with Stevens in the majority. But O’Connor’s vote was shaky; she had a long history of voting against racial preferences. So Stevens gave her the opinion. Progressives hailed the results: a vigorous defense of affirmative action in schools.

Stevens did the same thing in a high-profile gay-rights case. The question was whether the right of privacy protected gay people from being thrown in jail for having consensual sex. Again the court was split, with Stevens in the controlling majority. Instead of keeping the history-making case for himself, Stevens wisely assigned the opinion to Kennedy. A devout Catholic, Kennedy was sure to be torn by the issue. Once again, it paid off. Kennedy wrote the strongest endorsement of gay rights in Supreme Court history—one that today is being used by advocates of same-sex marriage.

Stevens, once called “a wily practitioner of coalition politics,” worked the hallways to get votes. When Guantanamo detainees brought a case to the court in 2008, the liberal justices reportedly didn’t want to take the case because they worried that Kennedy would join the conservatives and uphold the Bush administration’s draconian detention policy. Stevens apparently visited Kennedy privately to discuss the issues in the case—something that, surprisingly, rarely happens in the Supreme Court. The court ultimately issued an historic ruling in a majority opinion authored by none other than Kennedy.

Among those on President Obama’s short list, one person stands out for having a proven track record of coalition-building. Before Elena Kagan became its dean, Harvard Law School had such a divisive atmosphere it was jokingly referred to as “Beirut on the Charles.” Kagan was able to unite the factions and, under her watch, the law school regained its stability and its status as the place law professors want to work.

Whomever takes Justice Stevens’ seat on the court will have trouble filling his shoes. Stevens knew what it took to create groundbreaking decisions that give life to the abstract principles embedded in our Constitution. His successor won’t have the sophisticated personal understanding of his colleagues—nor, significantly, the seniority to assign opinions—that Stevens employed so well.

Adam Winkler is a constitutional law professor at UCLA.