Twenty years ago this week, on May 21, 1992, MTV broadcast the first episode of The Real World, creating a seismic disruption to our culture. Reality television and nonfiction entertainment may still struggle for respect, but it’s hard to imagine an era when Jonathan Murray and Mary-Ellis Bunim—picking up where An American Family had left off almost 20 years earlier—had to convince MTV that filming seven strangers for a few months would produce exponentially entertaining narrative television.

During its life, the series has introduced us to many people, including those who’ve gone on to impressive careers: actor Jamie Chung, WWE wrestler Mike “The Miz” Mizanin, Congressman Sean Duffy. It illustrated and humanized issues such as race, AIDS, eating disorders, prejudice, and addiction. It gave us unflinching portrayals of real gay men and women’s lives, and gave us the Las Vegas suite in which Britney Spears stayed after being briefly married to Jason Alexander for a single evening. It celebrated the frivolity and camaraderie, pain, and pleasure that come with living with other people, even strangers.

Despite all that, and its impact on both my television viewing habits and life, I’m indifferent about the anniversary of its birth, because I fell out of love with The Real World long ago.

Its 27th season will debut next month, set on St. Thomas, and I won’t watch; I haven’t done more than dip in for a few minutes for the past few years, because I no longer recognize the show that I once couldn’t tear myself away from.

I can’t remember when exactly it leapt from fascinating entertainment to ridiculousness to worthlessness. Perhaps it was during the drunken orgy that was the first (there’ve been two) Real World: Las Vegas, or during one of The Real World: Denver’s fights, but once its DNA became saturated with alcohol, I no longer recognized nor cared about the people the cameras followed.

But as responsible as The Real World is for helping to usher in a me-centered era in popular culture, in which anyone can became famous and rich—or thinks they can—it actually refuses to care about me, or you, or our complaints about the show.

That’s The Real World’s most remarkable achievement: surviving 27 seasons despite having alienated the people who made it popular.

Since day one two decades ago, the public has been passionate about and invested in The Real World, even if that was only to criticize its content or conceit. The most typical criticism used to involve the absence of reality involved in living rent-free in a lavish space with cameras rolling 24/7; now, especially from those who grew up watching the show, it centers on the cast not having lives outside of TV. The series that gave us a stormy, intelligent argument on a New York City street about race between people with jobs and lives has evolved into a frat party.

The range of opinions throughout the years about the various seasons and casts has been dramatic. For example, some fans thought The Real World: London was boring, and in comparison to the San Francisco season with Pedro and Puck, perhaps it was, though I loved it. Early seasons were accused of being contrived when producers forced the cast to create a business—Delicious Deliveries in Miami—or work together at some kind of job, like with kids in Boston. (Cast member Montana let the children drink wine.) The Las Vegas cast seemed to be the first to fully embrace hedonism as both the means and end of their existence.

The show has essentially ignored all of criticism, and evolved by staying with its target demographic, not aging with its die-hard fans. Most shows of its age desperately try to change and grow to stay fresh and keep its audience engaged, but The Real World casts rarely feature young people who’d be relatable to older viewers.

More important, the series has both mirrored and directed our culture, inspiring people to live their lives in public instead of having lives, and at the same time has shown us the consequences of that. It’s even spawned an ecosystem, the Challenge competition series, to sustain the cast members with camera time and cash after their months of rent-free living expire.

The Real World exists to document life for people 18 to 25—and sell ads to MTV’s 12- to 34-year-old demographic—and in 2012, that life includes being a star for the sake of being a star. In an era of recording one’s own life on Facebook and YouTube, that shouldn’t be surprising. While people with impressive resumes (or other experience, such as gay porn) may still appear on the show, the life they live is now focused around the show, rather than the show focusing on the lives they live.

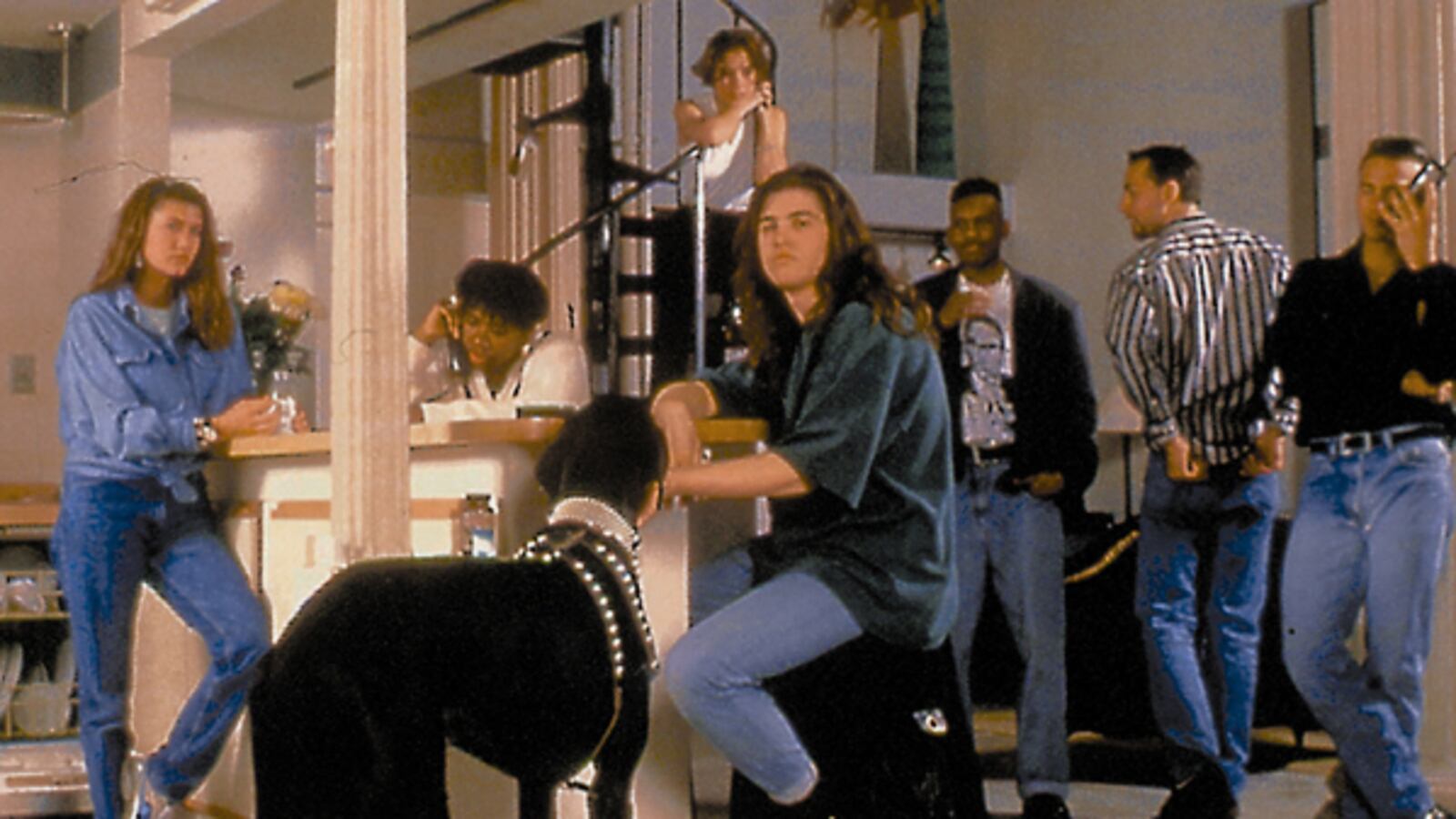

Long gone are the days when a hip-hop artist, a journalist, a painter, a model, a rock group member, a folk singer-actress, and an aspiring dancer would come together for an experimental documentary show, as Heather, Kevin, Norman, Eric, Andre, Becky, and Julie did back in a New York City loft, learning from each other while continuing to explore their individual interests.

Or actually, maybe that’s exactly what the cast members still do. Maybe it’s just that they’re unrecognizable because its cast members are now 10 or 15 years younger than those of us who began watching when the cast members were five or 10 years older than us. Early Real Worlders had ambitions and problems that we could aspire to or learn from or mock; current Real Worlders have lives we’ve already lived, never mind that they’ve grown up in an entirely different world.