Cancer is hell. Part of the reason it wreaks havoc on your body so effectively is because it can evade and circumvent the immune system remarkably well. Without clearer warning signs that something is wrong, a tumor grows and metastasizes under the radar with very few obstacles. Once signs of the cancer are finally detected, it may be in a late stage where a patient has few options for treatment.

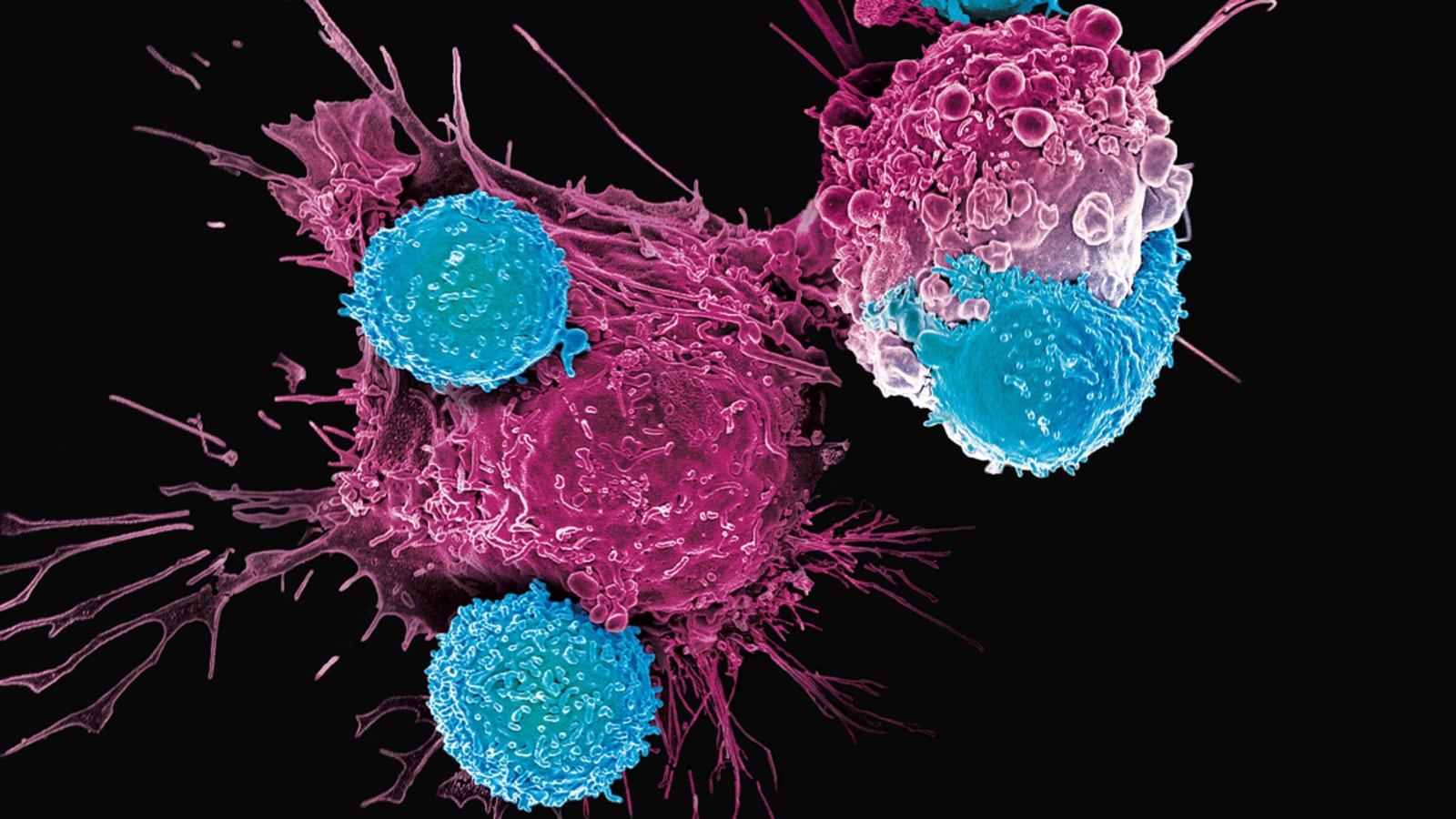

How are cancer cells able to avoid the immune system’s defenses? Scientists have been obsessively trying to answer this question for over a century now. A new study published in Nature Immunology Thursday has found that T cells, an integral part of how the body mounts an immune response against pathogens and deadly invaders, become “exhausted” within mere hours of encountering a tumor.

“The idea has been that T cells that are exposed to an antigen (such as a tumor or pathogen) for a long time are working and working, and then at some point they sort of peter out,” Mary Philip, an assistant professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and a co-author of the new study, said in a press release.

Previous studies had found that T cell activity became dysfunctional after five days of exposure to tumors, but the new study shows that it occurs much more quickly. “I don’t think anyone expected that within six to 12 hours, T cells would look dysfunctional or exhausted; that’s a very fast time window,” said Philip.

That’s discouraging news, but the findings do open up new avenues of research for how immunotherapies targeted against cancer could be made to prime T cells and prevent them from such exhaustion moving forward.

For the new study, the researchers bred mice that had been genetically entered to develop liver tumors as they age in an analogous time frame that human patients would. The researchers tracked immune responses to the tumors, and were able to glimpse how T cell activity rose and fell. They also ran a parallel study of how mice T cell responses behaved in response to an acute infection.

Besides giving us a more specific time frame for when T cell exhaustion occurs, the new study found that certain genes associated with a response to infection did not turn on when the immune system had to combat a tumor. The researchers hope that drilling down on these genes and finding ways to make them switch during a battle with cancer could be an effective way to help patients’ immune systems purge tumor cells from their bodies earlier.

Immunotherapy itself is having a big moment these days, as more and more physicians believe finding ways to supercharge the immune system against specific forms of cancer, personalized to the patient. The new findings don’t necessarily pave a path toward a new kind of immunotherapy, but they lay the groundwork for such an approach—and could one day end up saving the lives of people who have few other options.