On Feb. 22, 1989, the music industry converged on the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles for the annual Grammy Awards. More than any other year before it, the event represented a messy collision between the old guard and the next generation. Although pop star George Michael won Album of the Year for his landmark Faith, and singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman won Best New Artist, other moments weren’t so forward-looking. Flute-augmented classic rockers Jethro Tull beat out thrash metal upstarts Metallica to win the first-ever Best Metal Performance award, while Public Enemy was one of several rap artists protesting the Grammys that year because the ceremony “refused to recognize rap music and hip-hop as a legitimate music category,” as Chuck D recalled in the 2022 Sinead O’Connor documentary Nothing Compares.

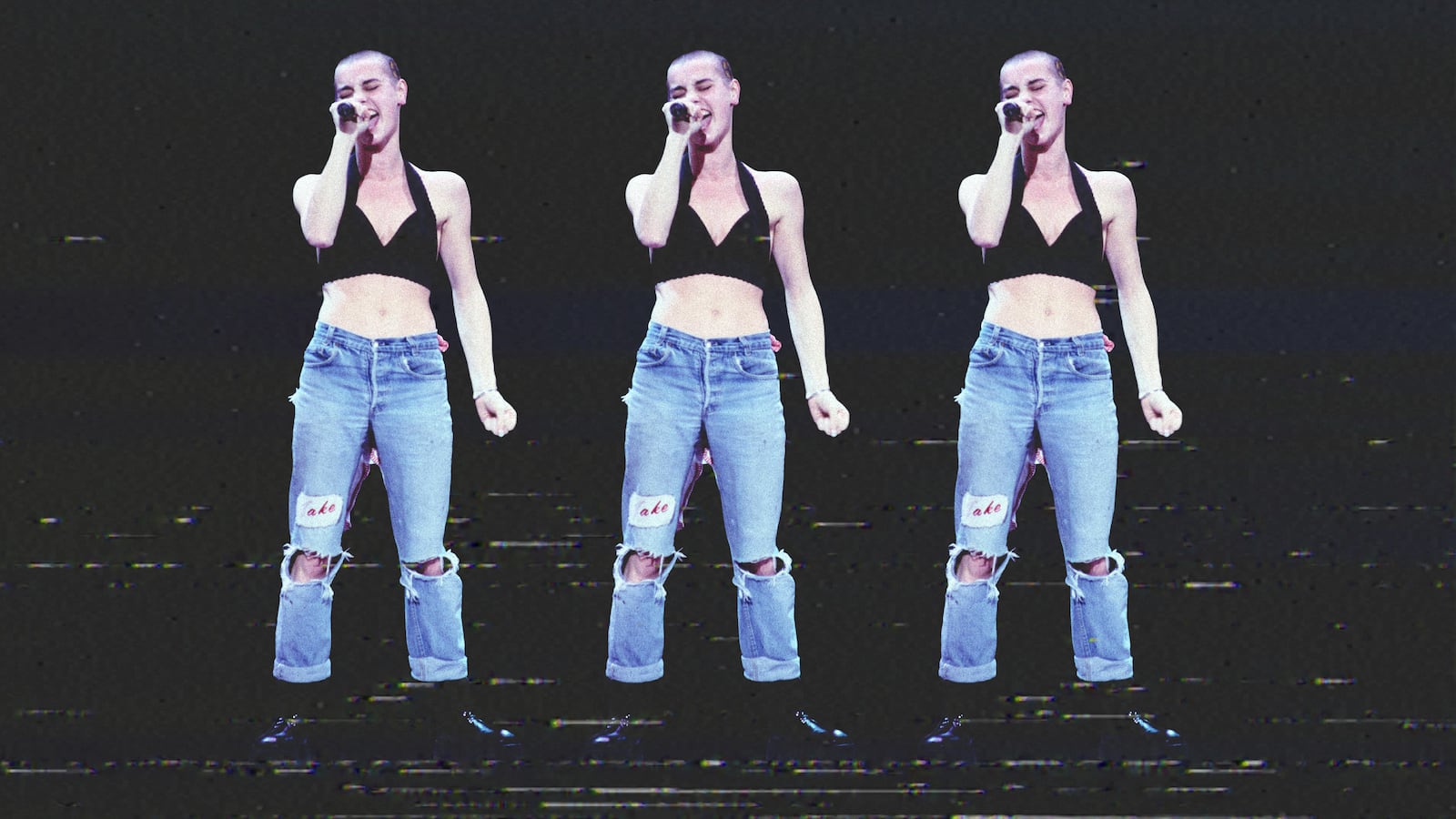

The performances that year also lamely played it safe—with the notable exceptions of Metallica, who stormed out of the gate with pyro blasts and the sound of gunfire, and O’Connor herself. The then-21-year-old Ireland native—who passed away this week at the age of 56—looked like a renegade, with her shaved head, combat boots, black halter top, and baggy ripped jeans. And her performance of “Mandinka” was likewise an act of low-key rebellion: She performed alone on a gigantic empty stage—no band, no vocal accompaniment, minimal production—thus introducing herself as a defiant, powerful force of nature.

As the churning guitars to “Mandinka” start, O’Connor strides out from backstage, looking a bit nervous as she gets her bearings. When she starts singing, however, any hint of hesitancy falls away. Lithe and confident, O’Connor shimmies to the side and spins her torso in time to the music, immediately in a focused groove.

She pours her heart into the soaring pre-choruses, singing lines like “I don’t know no shame / I feel no pain / I can’t” with her eyes closed in concentration. And by the time she reaches the sky-scraping chorus (“I do know Mandinka”), she stares straight ahead at the audience, stomping her feet in time to the buoyant beats in a burst of nervous energy. Throughout the performance, she radiates contentment; in fact, her joy is infectious. Even though she’s alone, there’s an intimacy to her delivery that’s deeply moving.

At the time, O’Connor certainly embodied the burgeoning alternative music underground, but attended the ceremony that year because she was nominated in the now-defunct category Best Rock Vocal Performance, Female for her 1987 debut album, The Lion and the Cobra. She was up against several newcomers (rocker Melissa Etheridge and soul-pop belter Toni Childs) and formidable veterans like Tina Turner, who ended up winning for her Tina Live in Europe LP.

Despite the loss, O’Connor soaked up the experience. In her 2021 memoir Rememberings, she reminisced about seeing jazz greats Sarah Vaughan and Dizzy Gillespie rehearse and meeting soul legends Al Green and Anita Baker. The latter artist “said she liked ‘Mandinka,’” O’Connor excitedly recalled. “She said, ‘Your voice is cavernous.’” Later, she expressed awe and excitement that Stevie Wonder was in the front row while she performed.

Despite her reverence for the occasion, however, O’Connor used her Grammys platform for some pointed social commentary and critique. She tied the arms of a baby’s onesie, worn by her then-young son Jake, onto the belt loops of her jeans, letting it flap around her waist as she sang. O’Connor later put the onesie on her mother’s grave, intending it as a “souvenir for her from the Grammys.” The writer Allyson McCabe also called the wardrobe choice “a middle finger to the executives at her record label who had warned her that motherhood and a career were incompatible.”

O’Connor topped off her outfit by painting Public Enemy’s yellow and black bullseye logo on the left side of her head—effectively giving the group, and the entire genre of hip-hop, a prominent place on network TV. In Nothing Compares, Chuck D called her gesture of solidarity “admirable” and added, “With Sinead O’Connor, you didn’t get the sense that she was just being pretentious or that she was fake. It was like, she seriously has issues with this.”

It’s true that O’Connor was firm in her convictions. Two years later, in 1991, Public Enemy protested the Grammys again over the ceremony’s refusal to televise the presentation of the rap categories. O’Connor—who was nominated for four awards that year, including Record of the Year—also boycotted for separate reasons, withdrawing herself from consideration and refusing to perform her nominated hit song “Nothing Compares 2 U” on the show.

“As artists I believe our function is to express the feelings of the human race—to always speak the truth and never keep it hidden even though we are operating in a world which does not like the sound of the truth,” she wrote in a letter at the time. In his own sign of solidarity, Living Colour lead guitarist Vernon Reid wore a shirt with O’Connor’s photo on it to accept the Grammy for Best Hard Rock Performance.

Institutions tend to not appreciate truth-tellers or people who refuse to uphold traditions, no matter how staid. O’Connor’s very public refusal to acquiesce to music industry schmoozing at the Grammys likely influenced the virulent reaction to her infamous 1992 Saturday Night Live appearance. After covering Bob Marley’s “War” on the SNL stage, she ripped up a photo of Pope John Paul II to protest sex abuse in the Catholic church, telling viewers, “Fight the real enemy.” It was a stunning gesture that caused an uproar and had a profound impact on her immediate commercial prospects.

Years later, O’Connor herself noted that the rip heard ’round the world defined her career “in a beautiful fucking way… But it was not derailing; people say, ‘Oh, you fucked up your career,’ but they’re talking about the career they had in mind for me. I fucked up the house in Antigua that the record company dudes wanted to buy. I fucked up their career, not mine.”

O’Connor added that she was “born for live performance,” which is undeniably true. At the 1989 Grammys, O’Connor’s presence—and comfort in her own skin, even as a 21-year-old who had never performed on such a big U.S. awards show stage—was galvanizing. She offered a different mode of self-expression that was inspiring to anyone who didn’t (or wouldn’t) conform to social expectations. And more than that, she demonstrated that it was possible to approach motherhood, womanhood, and a music career on her own terms.