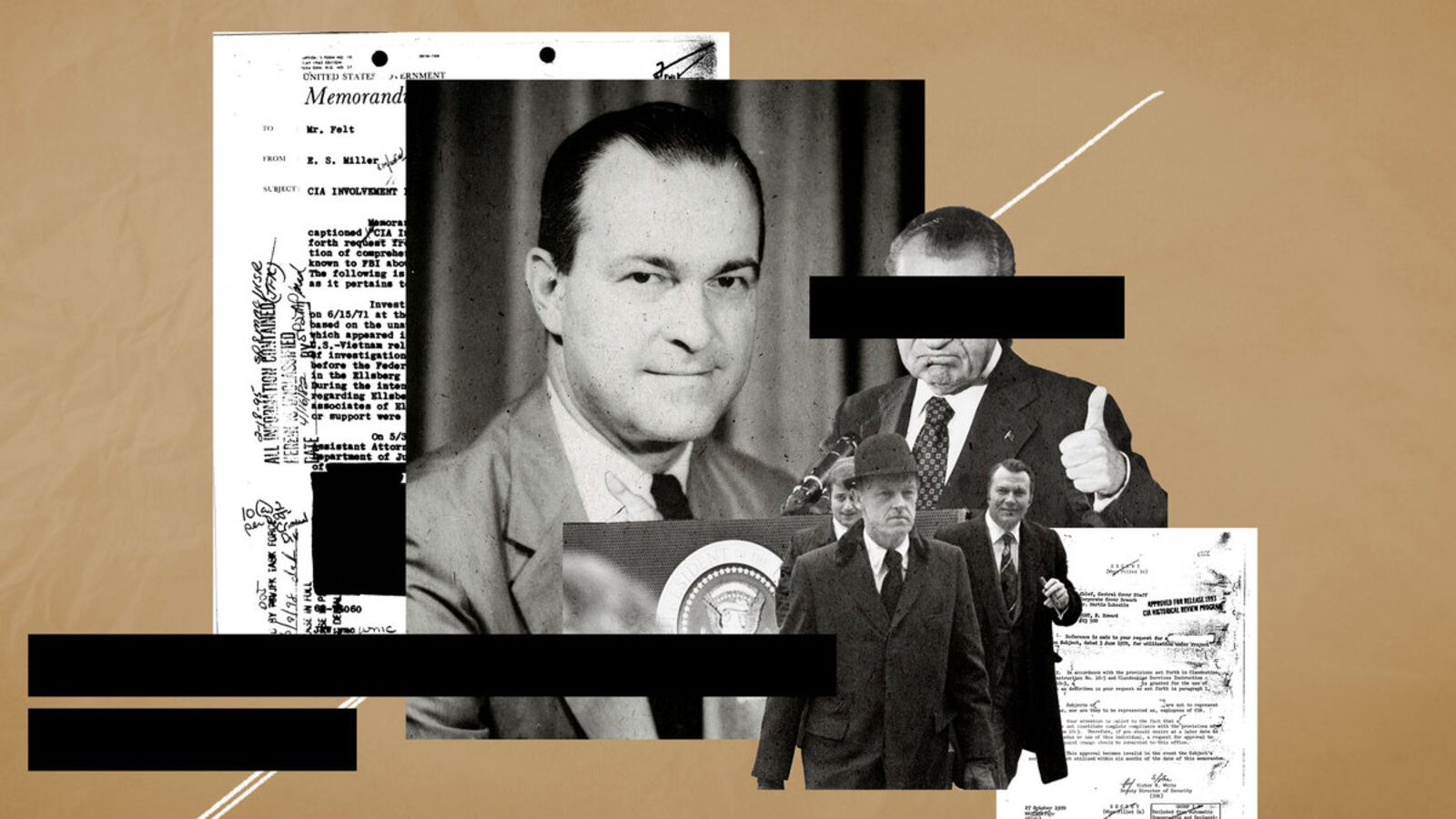

When asked about the role of the CIA in the Watergate affair, Senator Howard Baker famously said, “There are animals crashing around in the forest. I can hear them but I can’t see them.” As co-chairman of the Senate Watergate committee, Baker filed an appendix to the panel’s final report raising what he said were unanswered questions about the actions of CIA director Richard Helms. The Agency, Baker suggested, knew more about the burglars than Helms ever admitted.

In writing a book about the complex relationship between the two ruthless Richards, Nixon and Helms, I found much to support Baker’s suspicions. Helms was far closer to burglar Howard Hunt than he admitted under oath. He and Hunt were longtime friends who lunched three to six times a year, sharing personal and professional confidences. Hunt gave Helms a wedding present in 1968. Helms returned the favor by promoting Hunt’s spy novels to powerful Hollywood friends as possible movie material. And there is compelling, if not conclusive, testimony from two CIA officers, that Hunt passed intelligence reports to Helms while working for the White House.

But I also discovered the full story is off-limits to the American people. Key details of the CIA’s relationship with three of the Watergate burglars are still shrouded in official secrecy, even on the 50th anniversary of the break-in that lead to the downfall of President Richard Nixon.

An October 1970 memo shows that the agency’s first statement about the burglars was false. After the arrest of five burglars in the offices of the Democratic National Committee early in the morning of June 17, 1972, the agency claimed that the men were former employees “with whom we have had no dealings since their retirement.” But the partially declassified memo shows that the agency’s Office of Security approved a request for “utilization” of Hunt for a project whose name is redacted. The memo was written six months after Hunt’s supposed retirement from the Agency and 20 months before the botched break-in.

At the time, Hunt was working at the Mullen Company, a Washington public relations firm, in a position he obtained with the help of letter of recommendation from Helms. The Mullen company was “utilized by the Agency for commercial cover purposes,” according to another redacted CIA memo. “In July 1971 Hunt informed the Agency he had been assigned to the White House staff but continued to devote part of his time to the Mullen company work,” the memo stated. The next four lines of the document are redacted.

That memo also explained the CIA connections of Robert Bennett, owner of the Mullen Company, but censored the details. A paragraph about Hunt’s employment stated, “Approval was issued on 19 March 1971 for Mr. Bennett’s use,” followed by a one line redaction.

In context, the deleted passages lend credence to the notion that Hunt may have been working on secret CIA operations while he was working for the Nixon White House, something the agency has always denied. The redactions, of course, also make it impossible to determine the truth.

A redacted FBI memo from May 1973 conceals details about Hunt’s role in breaking into the office of the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg, the former Defense Department analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times. The memo was addressed to Acting FBI Director Mark Felt who was serving as a confidential source, known as Deep Throat, for Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward.

Ten lines about the “CIA involvement in the Ellsberg case” are redacted, including information about Hunt’s grand jury testimony, which is usually not made public. The redactions make it difficult to reach conclusions about CIA involvement with Hunt, other than the government is determined to conceal it well into the 21st century.

The details of the CIA’s post-retirement support for burglar James McCord, a former senior security officer, also remain classified. Helms told the Senate Watergate Committee that he had met with McCord “a few times,” giving the impression he barely knew the man. In fact, Helms wrote McCord a letter of commendation upon his retirement, and McCord displayed an autographed photo of Helms in his office that was inscribed “with deep appreciation, Dick.” [Underscore in original].

One redacted CIA memo lists the many undercover operatives who interviewed for jobs at a private security firm started by McCord in 1970. Twelve lines about an undercover operations officer who knew both McCord and Hunt are still withheld from public view.

In May 1973 investigators learned that McCord had sent four letters to Helms after his arrest outlining his plans for defending himself at trial. The Agency did not share the letters with the FBI, despite their obvious relevance to the Watergate investigation. Three top CIA officials were called by the House Armed Services Committee to explain the Agency’s action. In a draft history of the Watergate affair, obtained in 2019 by the conservative watchdog group Judicial Watch, five lines of commentary on their testimony are redacted. The nature of McCord’s back-channel communications to Helms is still too sensitive for the agency to disclose

The agency eventually admitted that one of the burglars, Eugenio Rolando Martinez, was on its payroll at the time of the break-in. As a full-time CIA contract employee from 1961 to 1969, Martinez had served as a boat captain on hundreds of sabotage and terrorism operations against Cuban targets. The names of the two case officers to whom he reported at the time of his arrest are redacted in the draft history.

In 2005, Martinez sat for an oral history with Timothy Naftali, then the director of the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda California. The Martinez’s interview is captured on two compact discs found in the library. One of the two disks is entirely classified.

So Howard Baker’s suspicions about the hidden hand of the CIA cannot be dismissed even today. The CIA animals crashed around in the Watergate forest a long time ago, but we are still not allowed to see the government records that document what they were doing—thanks to a regime of official secrecy that prioritizes the CIA’s interests over the historical record of the greatest political scandal in American history.

Jefferson Morley is author of the forthcoming book Scorpions’ Dance: The President, the Spymaster and Watergate (St. Martin’s Press).