In the odyssey of 20th-century English literature, large looms the myth of Sylvia Plath—talented, tortured, fame-hungry and ferocious.

The feminists claimed her as their own modern-day Sappho, a doomed Iphigenia sacrificed on the altar of genius by her philandering husband, Ted Hughes. Her fellow lyricists, meanwhile, declared her “hardly a woman at all, certainly not another ‘poetess’” but—in the words of Robert Lowell—a great classical heroine, “a Dido, a Phaedra or Medea” whose poems played “Russian roulette with six cartridges in the cylinder.”

She saw herself in madder, more irredeemable terms—in her lines, she became the damned Electra, the “Lady Lazarus,” a worm-husbanded Persephone gone to seek the narcotic song of the dead. She was the poet of Maenads and mausoleums, hanging men and thalidomide, whose verses teemed with all those ruins and rooks, dark houses, cadavered rooms, “white-jacketed assassins” and ravaged things. Ravens and graves wreathed her writing desk.

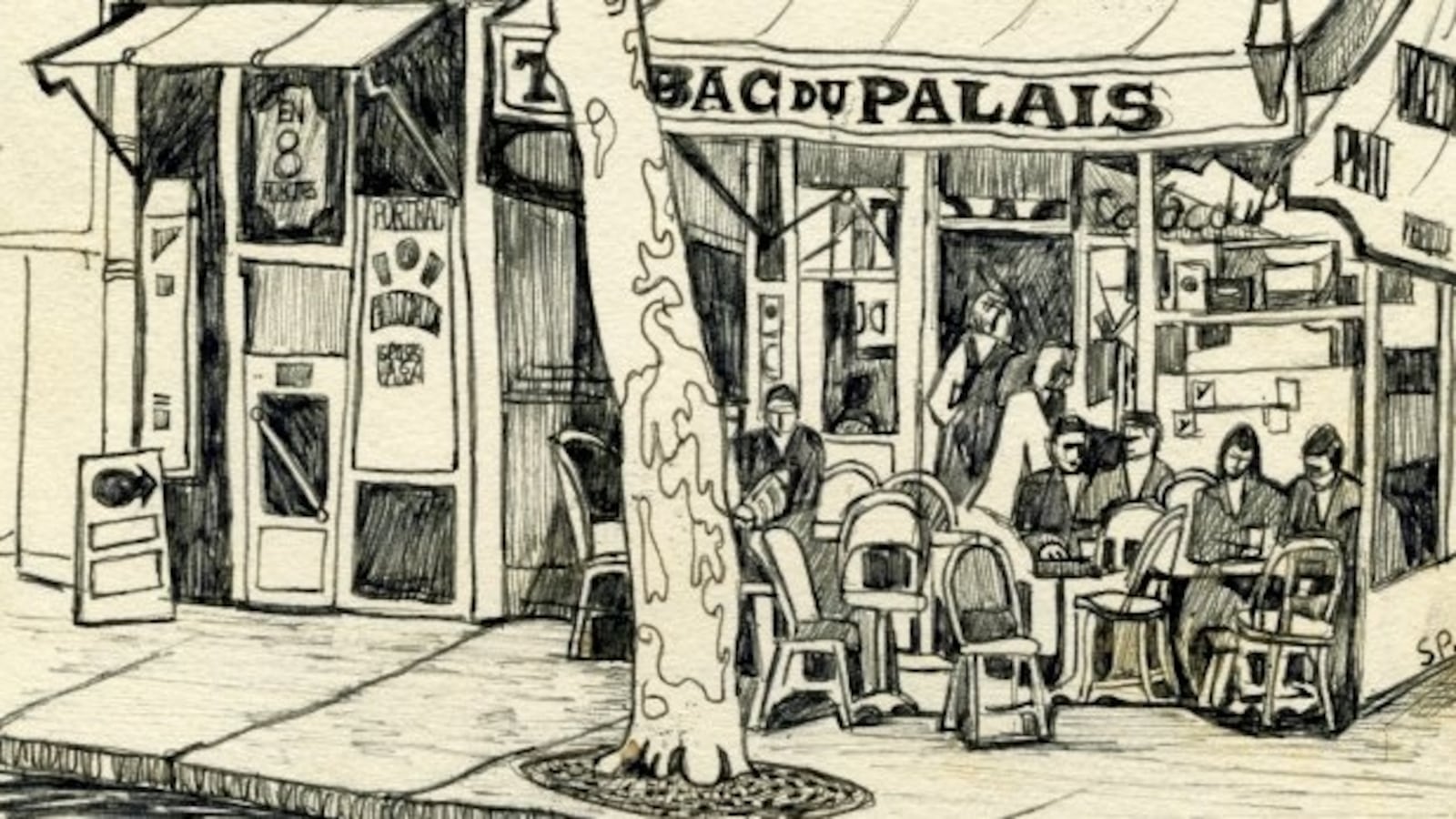

Some might find it strange, then, to leaf through the new book of her personal sketches—named, aptly, Sylvia Plath: Drawings—and find a world of stolidly quotidian odds and ends. Gone are the barren women and beasts, the mangled nerve-ends and the “flesh laid waste”; instead, we find Beaujolais bottles and horse chestnuts, “curious cats “and sleepy Spanish towns. This is the stuff of Cézanne—bourgeois, burghered still-life’s—not an asylumed Van Gogh. There are busy streets, Baudelairean in their bustle; the graceful curves of Catholic cathedrals; sensible umbrellas and downy thistles; teakettles, women’s shoes, tabacs and jaunty kiosks; cooking stoves and seagoing sardiniers; and a fine study of maunching bulls lounging in the grass of some elysian English field. No wild furies here, thank you very much.

The pictures, which originated in the private collection of Plath’s daughter and executor, Frieda Hughes, and which were auctioned off in 2011 at the Mayor Gallery in London, were composed between the years of 1955-57 at a particularly blissful time in the poet’s turbulent life. Studying abroad on a prestigious Fulbright at Cambridge, secretly wedded and swooningly in love with her Yorkshire husband (“that big, dark, hunky boy, the only one there huge enough for me”), Plath bounced between England, France and Spain on an extended honeymoon before decamping for America with Hughes to teach at the Five Colleges in her native Massachusetts.

“I enjoyed the last week in Benidorm more than any yet,” Plath wrote to her mother, just back in Paris from the Costa Blanca, in a letter included in the book. “Went about with Ted doing detailed pen-and-ink sketches while he sat at my side and read, wrote, or just meditated. He loves to go with me while I sketch and is very pleased with my drawings and sudden return to sketching.”

Hughes himself memorialized the ritual in his last book of poems, Birthday Letters, published on the eve of his death from cancer in 1998. In “Your Paris,” he writes of Plath and her “immaculate palette,” ecstatically drawing les toits et la ville, while he, “Like a guide dog, loyal to correct your stumblings,/Yawned and dozed and watched you calm yourself/With your anaesthetic—your drawing, as by touch/Roofs, a traffic bollard, a bottle, me.”

Indeed, art soothed Plath’s otherwise white-hot personality. “It gives me such a sense of peace to draw; more than prayer, walks, anything,” she wrote to Hughes (aka “dearest darling Teddy”) in a letter from October 1956, four months into their marriage. “I can close myself completely in the line, lose myself in it.” Hughes echoed this salve-like quality of the pen in a late poem: “Drawing calmed you…you drew doggedly on, arresting details/Till you had the whole scene imprisoned.”

For such an auditory writer—she once told the BBC that her verses were “written for the ear, not the eye: They are poems written out loud,” possessed of a “deep mathematical inevitability,” as Hughes noted in his preface to her Collected Poems—Plath seemed to get a great stimulus from forms, colors, and lines. In another interview, Plath declared, “I have a visual imagination. For instance, my inspiration is paintings and not music when I go to some other art form … I see these things very clearly.”

Even before she became the high-strung, bipolar bobby-soxer of The Bell Jar, Plath indulged an artistic streak. She drew from an early age—illustrated letters from a seven-year-old Sylvia were found in the family attic—and, alongside literature, she studied art at Smith College, producing some sensuous self-portraits during her time there. In her twenties, she took a liking to the “primitives” and spun poems off of the canvases of de Chirico, Rousseau and Klee.

“I have got out piles of wonderful books from the Art Library (suggested by this fine Modern Art Course I’m auditing each week),” she wrote to her mother in 1958, “and am overflowing with ideas and inspirations, as if I’ve been bottling up a geyser for a year.” (In typical Plathian fashion, darker works also caught her eye—she used Brueghel’s The Triumph of Death as inspiration for a particularly grim poem, in which she imagined a morgue where “snail-nosed babies moon and glow” in jars of Formaldehyde.)

Flemish masters aside, Plath’s private journals show her realization, as critic Michiko Kakutani once put it, “that her psychological well-being depended upon her remaining anchored to ‘some external reality,’ some shared ordinariness of ‘laundry and lilacs, daily bread and fried eggs.’”

In this way, her sketches helped tether her to daily life, just as teaching at Smith did. Facing down her first semester as an instructor at her alma mater, she wrote, “Once I get into the blissful concreteness of this job, my life will catapult into a new phase: that I know. Experience, various students, specific problems. The blessed edges and rounds of the real, the factual.” Such routines served as a bulwark against her tortured 3AM monologues, her manic mood swings, her immense jealousies and gnawing fears.

We’ve seen this before, Plath’s embrace of everyday ordinariness as a way to mask the vivid, roiling terrain of her great mind—mostly notably, in her missives to her mother, Aurelia, collected posthumously in Letters Home, as well as in the exchanges between the two included in Sylvia Plath: Drawings. Here, Plath plays the chirruping co-ed, prattling on about tennis dates and 50’s fashion and mastering her beloved Joy of Cooking. This is the silly “loving Sivvy” who crows over getting an article in “THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR,” and chats breezily to her “dearest of mothers.” She speaks of delightful days on the Seine (“I really love this city above any I’ve ever been in; it is dear and graceful and elegant and what one makes of it”), of being the dutiful student who “can write and do good exams if my Teddy is with me.”

This Plath fretted over how to be a happy housewife—“must not nag,” she reminded herself in her journal—and toted cookbooks around in her honeymoon luggage. This Plath is the straight-A student, the golden girl of Amherst. This Plath oozes that “old need of giving mother accomplishments, getting reward of love.”

But like Hamlet toying with Polonius, playing the jester to mask his true suspicions about Denmark’s dark prison, Plath’s letters have the air of seeming to protest too much. For even as she mailed off her airy epistles, she scrawled furious screeds against her mother in her private diaries. Aurelia was “a walking vampire,” “a murderer of maleness,” “deadly as a cobra under that shiny greengold hood.”

The bile was violent and primal. “How do I express my hate for my mother?” Plath asked herself. “In my deepest emotions I think of her as an enemy: someone who ‘killed’ my father, my first male ally in the world.” (As Joyce Carol Oates notes in her review of Plath’s Unabridged Journals, “One would never guess from this hysterical outburst that Plath’s father died of diabetes [or] that her mother worked at two jobs to support Sylvia and her brother Warren.”)

Her vituperous negativity (described by Hughes as “Sylvia’s particular death-ray quality”) also skulks, shadowy, behind her drawings. Writing to Ted about sketching those placid bulls in their dewy paddocks, she brooded, “Various people biking past or strolling to Grantchester stared at me, way out there, drawing the cows...I feel, in my singular passions and furies, that I become a gargoyle, and that people will point. One thing, I certainly prefer being alone; I shun people like poison; I simply don’t want them…”

Indeed, cheery as her modellos might otherwise seem, the book of sketches courses with the undercurrent of what is left unsaid—such ambition, such madness, the tragic end—and it’s almost impossible for the intensely symbolic cosmology of Plath’s apocalyptic poemscapes not to bleed onto the images. How to look at the Cambridge street scene and not recall her Dark Houses with their “eelish delvings”? Or gaze on the cathedral and not hear her “Mary’s Song”: “The Sunday lamb cracks in its fat…it is a heart/This holocaust I walk in,/O golden child the world will kill and eat”? Or not to read into the curving buds of her “Meadow-Flowers” the glowing incantation, “Stars shoot their petals, and suns run to seed”?

Her “Alicante Lullaby” lingers over the scenes of bougainvillea and white-washed alleys in her Carrero dels Gats sketch, just as her “Suicide Off Egg Rock” (“He smouldered, as if stone-deaf … His body beached with the sea’s garbage”) oozes in the mud of her Cape Cod boat scenes. It’s a testament to the power of her poetry—it was the blood-jet, after all, and in death as in life, it spurted over everything she touched.

It’s impossible, too, not to grapple with the "legend of Ted and Sylvia," as critics have called it—for it was also the blood-jet, one whose ups and downs inspired Plath’s most productive bursts of creativity. (As a mooning newlywed, she mewled, “how creative Ted’s made me!” while her last poems, written in a wintery despair after Hughes had run off with Assia Wevill, are electric in their searing intensity.)

His legs bestride her legacy, whether the Plath-heads like it or not—he’s there in the introduction, since it was Hughes who bequeathed the sketches to Frieda and her brother; he’s there because of his Birthday Letters, which reanimate Plath at her palette; he’s there in one of the finest drawings of the book, a portrait Plath made in 1956. Hughes’s handsome, aquiline features are chiseled in ink—his poet’s five o’clock shadow, his boyish floppy locks—as he gazes pensively off, in search of some elusive line. The same year, Plath wrote “Ode for Ted,” which teemed with the vitality of green things and warming earth: “Ringdoves roost well within his wood,/shirr songs to which mood/he saunters in; how but most glad/could be this adam’s woman.”

They were both poets of the elements and their aggressive attraction was earthshaking, right from the very beginning.

When they first met at a literary party in Cambridge, Plath found him “the one man in the room who was as big as his poems, huge, with hulk and dynamic chunks of words; his poems are strong and blasting like a high wind in steel girders. And I screamed in myself, thinking: oh, to give myself crashing, fighting, to you.” A born seducer, Hughes pulled her aside for a kiss, ripping off her headband; she responded by biting his cheek and drawing blood. Their mutual raw power whipped through their poesy, blackening the literary world like the barren heaths and hardscrabble crags of Hughes’s Yorkshire moors. Plath drew this “substanceless blue/pour of tor and distances” during a 1956 visit to Haworth, in her sketch Wuthering Heights Today.

Five years later, on a visit to her in-laws, she wrote her “Wuthering Heights” poem about that stony, savage place: “If I pay the roots of the heather/Too close attention, they will invite me/To whiten my bones among them.” Decades after her death, Hughes wrote a response breathtaking in its bleak and desolate beauty: “You breathed it all in/With jealous, emulous sniffings. Weren’t you/Twice as ambitious as Emily? … what would stern/Dour Emily have made of your frisky glances/And your huge hope? Your huge/Mortgage of hope.”

This wild power is sublimated in Sylvia Plath: Drawings—but perhaps we can forgive Plath, and Frieda, for turning away from the thunderstorm, if only for the space of a few sketches. For years, Plath struggled to contain her “two electric currents … joyous positive and despairing negative—whichever is running at the moment dominates my life, floods it.” On February 11, 1963, the negative won out: in a flat once inhabited by Yeats, where she’d moved after separating from Hughes, she sealed her young children in their rooms with wet towels, put her head in her oven, and gassed herself.

Six years later, Hughes’s mistress Wevill killed herself and their four-year-old daughter in a copycat suicide. Hughes spent the rest of his life “permanently bending” at their open coffins. Eleven years after his own death, his only son took his life, as well. So let us linger in these gentle fields with their lowing cattle and their ripening seeds, for they constitute a brief time when Plath was happy, before the love turned sour, before the thick losses—before everything held up its arms weeping.

***

A century prior to Plath’s supernovial life, another hugely ambitious Amherst poet poured her own brooding mind into thousands of lines on immortality and death.

The similarities between Plath and Emily Dickinson are both facile and profound: they inhabited the same small corner of New England, though Dickinson, unlike Plath, never ventured beyond the familiar confines of Massachusetts. Both received little fame in their lifetimes, and yet tended in secret to their posthumous legacies—before killing herself, Plath left a carefully-arranged magnum opus of her poesy on her writing desk, while Dickinson squirreled away many of her 1,800 poems in a bureau drawer, sewn carefully into bundles. (Only 10 of these appeared in her lifetime, none of them under her own name.)

The women both percolated with a leeching childlike neediness, a soul-sucking intensity that exhausted friends and would-be lovers alike. (“I never was with any one who drained my nerve power so much,” attested the abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, one of Dickinson’s longtime correspondents. “Without touching her, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her.”) As with Plath, Dickinson was a densely symbolic poet—all those flowers imbued with private meanings—who often spoke, as critics have noted, in a proleptic tone that seemed to come from deep within or beyond the grave.

That eerie, ethereal voice—peeking out from the barest of slantwise lines—incandesces the pages of The Gorgeous Nothings: Emily Dickinson’s Envelope Poems, out this month from New Directions.

The tome presents the “scraps,” as they’re known within Dickinson scholarship, where Emily penned her snippets of poems on scrippets of paper. In the introduction, editor Jen Bervin notes, “These envelopes have been opened well beyond the point needed to merely extract a letter; they have been torn, cut, and opened out completely flat, rendered into new shapes … Dickinson was not blindly grabbing scraps in a rush of inspiration, as is most often supposed, but rather reaching for writing surfaces that were most likely collected and cut in advance, prepared for the velocity of mind.”

The fragments—which reside in the Amherst College Library archives—are ordered chronologically, and then indexed in the back of the book with a scholar’s categorical care: “Envelopes with Cancelled or Erased Text”; “Envelopes Turned Diagonally”; “Flaps and Seals.” They show a febrile mind spilling over onto the smallest spaces—Dickinson wrote right-side up and upside-down, triangularly, feverishly. Most intriguingly, for academics, some of the pen-scratches show Dickinson playing with several variations of a word or line, feeling out the right sound like a merchant weighing a bag of gold.

One can imagine these papers piled high on Dickinson’s writing table in her austere room—it held a sleigh bed, a bureau and a cast-iron stove—in the household she grew up in and never left. From this eremitical sanctuary, where, in later years, she secluded herself from almost all physical contact, dressing in white and composing torrid letters to intimates, she churned out an inexhaustible torrent of verse that thrummed with solitude and fiery visions.

Dickinson played up the contrast between her sterile surroundings and her tremulous poems: “Excuse/Emily and/her Atoms/The North/Star is/of small/fabric but it/implies/much/presides/yet.” Or, as Wentworth wrote in a credo to young bards that provoked Dickinson to launch their two-decade correspondence, “There may be years of crowded passion in a word, and half a life in a sentence.”

Of course, for all her eccentricity, Dickinson possessed a playful and lively wit, which peeps through on her papered flaps. “There are those/who are shallow/intentionally/and only/profound/by/accident,” she scribbled. Or this cheeky one: “Not to send/errands by John/Alden is/one of the/instructions of/History.”

This is the Emily who penned the humor column for her school’s magazine, the saucy socialite who kept up a gay correspondence with some 90 pals. Here is the 15-year-old girl who went riding out with Amherst’s most eligible suitors, not the desperate spinster who fell agitatedly in love with a succession of married men. This is the Emily who once wrote, wickedly, “House is being ‘cleaned.’ I prefer pestilence.”

This Emily seems a different person entirely than the one whose mind gnawed on dying and death. In her poems, one can find instances of drowning, premature burial, the gallows, the guillotine, freezing, shooting and stabbing. She is the oracle of loss, loneliness, of long absences and the madness they produce.

“Long Years/apart- can/make no/Breach a/second cannot/fill,” she wrote, perhaps wistfully. The grave lies at the end of many of her envelope verses: “The vastest Earthly Day/is shrunken small/By (shriveled/dwindled) one Defaulting/Face/Behind/a Pall.”

Scholars have linked this morbid bent to the many deaths and illnesses among her friends and family members, which they say served as the tipping point for an already sensitive and fragile spirit. Or maybe Dickinson was just macabre. How many other proper young women in her Holyoke social circle preferred to spend their time composing sentences like, “Doom is the House without the Door”?

While there’s something familiarly Calvinist in such brimstone language, Dickinson’s poems seem to reject—or, at least, seriously tussle with—the visions of heavenly paradise that awaited good 19th-century Christians. “The doubt, like the mosquito, buzzes round my faith,” she once wrote.

Even as her poems seethe with religious mystery and the language of the Bible—those drums of Judgment Day, the stone rolled away from the tomb, the signs and wonders, the apocalyptic battles of man and beast—this doubt plagued her: doubt about God’s benevolent intentions towards mankind, doubt that the Gospels' promise of eternal life might be a lie—that death is, in fact, absolute. While Plath is Greek in her understanding of Thanatos and Eros, Dickinson is solidly Old Testament—she is Jacob, wrestling with a God who seems bent on annihilating her.

It’s a God to whom she pleas in one of the rawest envelope scraps: “Some Wretched/creature, savior/take/Who would Exult/to die/And leave for/thy sweet/mercy’s sake/patience-/Another Hour/to me.” This is not a poet half in love with easeful death, but one clinging to life and terrified by the quicksand passage of time.

She writes of the bleakness of eons, the “embers/of a/Thousand/Years”: “As old as Woe-/How old is that?/Some Eighteen/thousand years.” Her answer to this relentless march towards eternal solitude was to recreate it, as if to conquer it. Just as she desperately sought intimacy and erotic rapture, always to find it elusive—and so decided to turn the tables by rejecting almost all visitors—she yearned so intensely for a release from the tomb that she spent her life entombing herself in her verse.

“How lonely this world is growing,” she wrote in 1850, “something so desolate creeps over the spirit and we don’t know its name, and it won’t go away.” This is bleak stuff, ferocious in the demands it makes on the self and on the universe.

Dickinson created a death-in-life in order to gamble on her poetry’s life after death. As one writer noted, “she lived a life for us that we could never live ourselves, which is what saints do. No wonder we hunger to know her.” Perhaps this is why scholars continue to pour over her thousands of scraps, why we run our fingers over the runes of her envelope poems, searching for clues to her riddles about life and death—hers, our own—in the hopes that those “That/fondled/them/when/they/were/Fire/Will gleam/and/understand.”

But Dickinson remains elusive, as she always meant to. “As there are/Apartments in our/own Minds that-/we never enter/without Apology-/we should respect/the seals of/others—,” she wrote on a scrap. Or, put another way, “To pity those that know her not/ Is helped by the regret /That those who know her, know her less/ The nearer her they get.”

This coy disappearing act was one she played up in life—appearing the birdlike victim, the breathless unworldly virgin, fleeing from the mailman and shyly offering loaded flowers to a select few visitors, teasing her imaginary reader, “The Soul selects her own Society/Then/shuts the Door.”

It made her an enigma even to her closest friends. “Sometimes I take out your letters & verses, dear friend … and when I feel their strange power, it is not strange that I find it hard to write,” Wentworth wrote in 1869. “If I could once take you by the hand I might be something to you; but till then you only enshroud yourself in this fiery mist & I cannot reach you, but only rejoice in the rare sparkles of light.”

These rare sparkles of light scintillate from the edges of her envelopes, hinting at the enigmatic undiscovered continents of the poet’s inner world. As one biographer noted, “This is her game, after all.” And she must have known it was a good one, one that would last a century and a half and still beguile. For as she herself admitted, ''The Riddle we can guess / We speedily despise.''