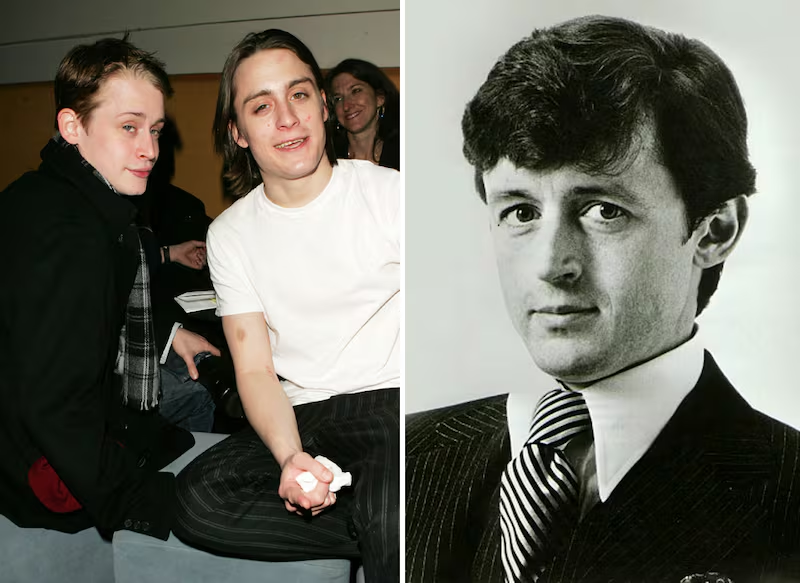

There’s a sequence in Igby Goes Down where the titular hero, played with seemingly effortless charm and panache by Kieran Culkin, struts down a Manhattan sidewalk in slow-mo like a miniature master of the universe. His floppy hair dances in the wind, and his uniform—prep school blazer, slacks, tie, knit rugby scarf, shit-eating grin—screams entitled insouciance. Igby was the Holden Caulfield of Generation Y; a sardonic slacker who sends his undercooked privilege back to the chef with both middle fingers held high. And his zesty turn saw Culkin emerge from beneath older brother Macaulay’s imposing cloak of fame, earning a Golden Globe nod for his performance. He was destined for stardom.

And then he disappeared.

Twelve years later, I’m loitering outside the stage door of Broadway’s Cort Theatre, where Culkin is starring in Anna D. Shapiro’s revival of Kenneth Lonergan’s celebrated coming-of-age tale This Is Our Youth. He plays Dennis Ziegler, a wiseass 20-year-old in Reagan Era New York who gets his jollies slinging weed and berating his considerably meeker pal, Warren Straub (Michael Cera). Though his artist-father subsidizes his life, Dennis thinks he’s got it all figured out. But he’s in for a rude awakening in the form of Warren, who’s got a bag filled with $15,000 in cash he lifted from his mob-connected Dad and a big ol’ crush on teen fashion student Jessica (Tavi Gevinson).

While much of the attention has been showered on Cera, who was introduced to the play by Culkin while filming Scott Pilgrim, it’s Culkin that steals the show with his whirling dervish of a performance, conveying the myriad frustrations of this iridescent adolescent.

He appears, ambling down the city sidewalk with a similar spring in his step—only this time, he’s sporting a t-shirt and jeans, as well as a purple headband holding back his mane. In his left hand, he’s clenching one of those black-gold striped plastic bags found at liquor stores. We say our hellos, and he guides me backstage, up three flights of stairs, and into his dressing room.

Once inside, he removes a cup of broccoli-cheddar soup from his bag and goes to heat it up. While he does, my eyes caress the strange pop culture tapestry on display. The first thing you notice is the five half-consumed bottles of top-notch single malt Scotch on an elevated shelf—Macallan, Balvenie, and his personal favorite: Lagavulin. Then there’s a bookcase filled with about a hundred miniature Marvel superhero figurines—except for the top-right shelf, he notes, which is all Mortal Kombat characters.

“That was my shit,” he says, motioning to the Mortal Kombat childhood relics. “People would get so pissed off at me because there’d be a line of people at the arcade behind this one guy whoopin’ everyone, and I’d come up—this little 9-year-old kid—and totally kick his ass.”

After discussing the lost art of the Babality, I joke that his character in She’s All That was also obsessed with video games—Sega Genesis, in particular.

“I forgot about that!” he says with a chuckle. “It’s one of those movies that always seems to be on—and I only know that because friends are always telling me, and then they’ll ask, ‘Why did you have hearing aids?’ and I’ll be like, ‘I don’t fucking know!’”

Speaking of She’s All That, my eyes then train on a glamour shot of that film’s star, Freddie Prinze Jr., that’s pinned to Culkin’s dressing room mirror. “Thanks for all the prison mail,” it says scribbled in black marker. “To my # 1 fan,” followed by the actor’s signature. The genial Culkin cracks up, before explaining that, after he made his theater debut on the West End in a 2002 revival of This Is Our Youth (playing Warren, opposite Colin Hanks and Alison Lohman), Prinze Jr. was in the cast that succeeded his, and left it in his dressing room as a mock-gift after paying him a visit one day.

You might say Culkin is a bit obsessed with Lonergan’s play, having performed it in London in 2002, in Sydney in 2012, and in Chicago earlier this year to prep for the Great White Way. Despite growing up on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and attending the child star-training institution PCS (Professional Children’s School), that’s churned out the likes of Christopher Walken, Uma Thurman, Sarah Jessica Parker, and Culkin’s classmate/pal Scarlett Johansson, he says it’s not really reflective of his childhood.

“This wasn’t really my upbringing, exactly,” says Culkin. “For 12 years, I wasn’t able to articulate what I loved about the play. It was just a feeling—the same way you fall in love with somebody. But this go-around, and hearing everyone discuss it, I’ve been able to flesh it out. It’s about that particular time in life where your childhood is clearly behind you and adulthood is the next step; where you’re stuck in that murky in-between.”

Many young actors have made their theatrical debut in Lonergan’s play, from Mark Ruffalo (in the original 1996 Off-Broadway version) to Matt Damon to Jake Gyllenhaal. I’m curious if it has to do with actors missing out on “that murky in-between” period of not being sure what profession they’d like to pursue, or even—in his case—their childhood.

He pauses. “I don’t think my childhood was that unusual, or that I missed out on my childhood,” says Culkin matter-of-factly. “And when a young person decides they want to be an actor, they’re basically saying, ‘I’ve decided that I want to be stressed out and pretty much have no guarantee that I’m going to have any job ever and that I’m probably going to be poor and eventually have to throw my hands up and go, fuck it, I guess I’m going to have to try something else. I’m 32 years old and I have no skills.”

Culkin, who is 32, is clearly talking about himself. I ask him why he thinks he has no skills.

“I don’t know how to type!” he says with an exasperated chuckle. “I can’t fuckin’ write. I’m not big enough to work construction. I wouldn’t be good at any other profession. I’ve thought about it a lot. I often think about getting out of this job, but I’m terrified that there’s nothing else.”

But it seems like you’re having so much fun out there on stage, I say.

“Once we opened, and after all the boring prep work was done, and we were able to run the play, it’s been really fulfilling,” he says. “It sounds stupid because it’s only three hours a day, but it seems to consume all that you do. I do the play, hang out with the wife for a few hours, and then I’m up all night wired after we run the play. But it’s all so fuckin’ worth it because I’m having a great time on stage. But the pursuit of work? I don’t have that thing in me.”

Which brings us to Igby Goes Down. After wrapping his 8-week run on the London stage in Jan. 2003, his manager convinced him to do 10 days of whirlwind press to campaign for a Golden Globe nod.

“It was really all her,” he says. “But sometimes, I’d show up to a movie premiere or something and think, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’” After successfully securing the Globe nomination and attending the ceremony, Culkin experienced a quarter-life crisis of sorts.

“All of a sudden, after that movie, there were what I guess people would call ‘opportunities,’ and I was signing on to a bunch of things I wasn’t sure of, and I found myself at the age of 20 with a career when I’d never once made a decision of what I wanted to do with my life,” he says. “I’d been doing this since the age of 2, then at 6 [as the bed-wetter, Fuller, in Home Alone], and then doing it in between school, and suddenly I’m here going, ‘Hold on.’” He takes a long pause. “There were three movies I was supposed to do and I just pulled out of all of them at once. It was February, and I told my manager, ‘No movies… just don’t call me until the summer. I really need time, I haven’t decided if I want to do this.’ And 12 years later, I still don’t know. I just get psyched for specific jobs.”

It would be seven years until he made his next onscreen appearance in 2009’s Lymelife. He was intrigued by the prospect of playing against his younger brother, Rory, who he claims may just be the most talented Culkin acting-wise.

“I was looking forward to the idea of acting with Rory because it’s the most trying thing,” he says. “He’s so brilliant, and I’ll look at him and get self-conscious and think, ‘Oh, he knows I’m full of shit.’ So my bullshit meter was on full blast, and it was terrifying.”

At this point, Culkin breaks out a bottle of his favorite stuff—the 16-year-old Lagavulin single malt Scotch.

“I can’t have you leave here without trying this,” he says, and pours me a little glass.

I’m still confused about his self-imposed post-Igby hiatus, so I ask him if, because of what he witnessed happen to his older brother Macaulay—the bullying and acrimonious split from his actor-father, Kit, and the lawsuit against him to protect his acting fortune—he has a built-in gag-reflex towards fame.

“I think if anybody saw real fame first or secondhand, they would not want to pursue it at all,” says a somber Culkin. “It is not attractive.”

In addition to the play, after splitting with actress Emma Stone in 2011, Culkin got married last year to Jazz Charton, a foley artist, and seems quite content in his personal life.

“Maybe this is because it’s just been over a year, but it’s fuckin’ amazing,” he says, beaming. “It’s way more beautiful than I thought it would be.”

Professionally, however, things remain pretty up in the air. He jokes that if he could exclusively work with his pals Lonergan and Cera, he’d “be set for life,” and that he and Cera have discussed doing another play together sometime in the near future. But for now, he’s relishing his time performing his favorite play on Broadway.

“This isn’t just a career goal, this is a life goal,” he says. “After this, everything is gravy. Maybe I’ll pursue more work after this, but I just don’t know.”

As I leave, I mention in parting how Culkin deserves some serious Tony Awards consideration for his performance. As I walk down the stairs, there’s a shuffling sound, and I turn to see Culkin pop his head out of the dressing room with a huge smile plastered across his face.

“Maybe I’ll see you on the awards circuit?!” he exclaims, barely containing his laughter.