Has there ever been an election like this one? The 2016 race is ferocious, rude, ugly, with parties and coalitions fracturing before our eyes. It’s also the first contest in years where public anger is trained on how government works and not just what it does. The state of democracy is on the ballot.

Bernie Sanders denounces the “billionaire class” and demands campaign finance reform. Donald Trump snarls, “Washington is broken” and brags that as a self-funder, he cannot be bought. Hillary Clinton, more muted, rolls out detailed plans for campaign finance changes and automatic voter registration. To add to the intensity, the looming Supreme Court nomination fight will tap public anger over Citizens United, the court’s most reviled recent decision. All just two years after an election in which voter turnout plunged to its lowest level in seven decades.

It might seem strange that the state of democracy itself might loom large as an election issue. But today’s arguments are not new. In fact, raucous debates over who should vote and how have always stood at the center of American politics. Intense focus on how Americans can improve their democracy seems to happen every half-century or so. Outsiders find a way to crash the political system, often through key elections, with inequality of wealth or power spurring a sharp move forward.

These battles have always been about more than formal rules. Voting laws have been seen as entwined with issues of the power of money in elections, gerrymandering, and other ways the system distorts decisions. For more than two centuries it’s been a raw and often rowdy struggle for power. Some of the heroes would have been more at home in House of Cards than in Selma. At times the breakthroughs came when sharp-eyed operatives realized that greater participation was in their enlightened self-interest. The fight for the vote has always been deeply, properly political.

***

Numerous issues divided the Founders from the start. (See “Cabinet battles #1 and #2” in Hamilton.) Among them: the rules for choosing the new government. Arguments first focused on the role of wealth in elections. At the time, only white men who owned property could vote. In 1776 John Adams shuddered at the idea of extending voting rights beyond that. “There will be no end of it,” he warned. “New claims will arise. Women will demand a vote. Lads from 12 to 21 will think their rights not enough attended to, and every man, who has not a farthing, will demand an equal voice with any other in all acts of state.”

James Madison was queasy, too—but only behind the closed doors of the Constitutional Convention. “In future times,” he worried, “a great majority of the people will not only be without landed, but any other sort of, property. These will either combine under the influence of their common situation; in which case, the rights of property and the public liberty will not be secure in their hands: or which is more probable, they will become the tools of opulence and ambition, in which case there will be equal danger on another side.” (Sanders and Trump?) Benjamin Franklin angrily put a stop to any talk of a wealth test for voting. “Some of the greatest rogues he was ever acquainted with, were the richest rogues,” he told the delegates. Madison offered a different spin when arguing for the Constitution to the public. In fact, he mouthed Franklin’s democratic credo. “Who are to be the electors of the federal representatives?” he asked in the Federalist Papers. “Not the rich, more than the poor; not the learned, more than the ignorant; not the haughty heirs of distinguished names, more than the humble sons of obscurity and unpropitious fortune. The electors are to be the great body of the people of the United States.”

Very quickly, the real world of American politics began to chip away at the certainties of the founding generation. Madison himself—who had denounced “faction” in the Federalist Papers—began to organize a political party, the Democratic-Republicans. Just four years after writing the Federalist Papers, he renounced his views and pronounced a new “candid state of parties.” It turns out, he now wrote, “Parties are unavoidable.” Meanwhile, the doomed Federalists, fearing the outcome of the 1800 election as John Adams ran for reelection, changed the voting rules in more than half the states. Massachusetts and New Hampshire even repealed the right to vote for president.

The fight to vote became a defining election issue in the early decades of the new country. By the 1820s, working-class white men demanded and won the vote. Much of the shift was engineered by politicians on the make, such as suave, elusive Martin Van Buren of upstate Kinderhook, New York. A colleague once bet he could force “the Little Magician” to give a definitive answer to a simple question. He asked Van Buren whether the sun rose in the East. “As I invariably slept until after sunrise, I could not speak from my own knowledge,” he replied.

In 1821, New York State held a heated Constitutional convention to decide whether to expand voting rights. Van Buren marshalled an aspirational coalition of what he called the “this class of men, composed of mechanics, professional men, and small landholders and constituting the bone, pith, and muscle of the population of the state.” A leading law professor, Chancellor James Kent, opposed him. “The tendency of universal suffrage,” Kent intoned, “is to jeopardize the rights of property, and the principles of liberty.” He warned of government by factory workers, retail clerks, and “the motley and undefinable population of crowded ports.”

Van Buren and his colleagues turned the Democrats into the world’s first mass political party. Its ranks were now filled with working men and small farmers, organized in a boisterous drive to win the White House. They backed the former general, Andrew Jackson. Modern Americans recoil from Jackson’s repugnant racial views and atrocities toward Native Americans. At the time, he was also seen as a tribune of democracy. He called the Bank of the United States “the Monster,” and denounced “special privilege” and government that helped the “rich grow richer.” Democracy became a fad. In 1824, turnout among white men was 27 percent; when Jackson was elected in 1828 it more than doubled, to 57 percent.

***

A century later, the health of American democracy was on the ballot again. In the wake of the country’s roaring rise to global power, the growth of cities, and massive concentration of wealth, citizens felt that their institutions were under siege, inadequate to the changing economy. There was, as Theodore Roosevelt described it, a “fierce discontent” among educated city dwellers as well as beaten-down farmers. More than is commonly recognized, the Progressive Era focused on political reform. As Boston’s “People’s Lawyer,” Louis D. Brandeis, put it, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

By 1912 the Seventeenth Amendment giving citizens the right to vote for U.S. senator was headed to the states for ratification. Backers saw it as a form of campaign finance reform, designed to stanch the corruption that came from state legislatures choosing U.S. senators. Congress also enacted a law banning corporate spending in elections.

After four years out of office, Roosevelt decided to run again for president; he sought the Republican nomination but was blocked by party mandarins. So he bolted and ran as the candidate of the Progressive Party. “To destroy this invisible government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day,” thundered the party platform, adopted in Chicago. At that convention Roosevelt bellowed to the activists, “We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord!” He urged an array of reforms, from direct democracy such as referenda and ballot initiatives to term limits for Supreme Court justices. Historian Sidney Milkis concludes, “TR’s crusade made universal use of the direct primary a celebrated cause, assaulted traditional partisan loyalties, took advantage of the centrality of the newly emergent mass media, and convened an energetic but uneasy coalition of self-styled public advocacy groups. All these features of the Progressive Party campaign make the election of 1912 look more like that of 2008 than that of 1908.” Roosevelt wasn’t even the most radical candidate in the four-way contest. That was Socialist Eugene V. Debs. “I like the Fourth of July,” Debs explained. “It breathes the spirit of revolution. On this day we affirm the ultimate triumph of Socialism.”

Roosevelt backed women’s suffrage. The Republicans and Socialists did as well. But Democrat Woodrow Wilson reflected his segregationist party’s ambivalence about voting. Voting, he explained, was a matter of states rights.

The day before his inauguration the next year, Wilson stepped off the train in Washington. Some Princeton students belted out a greeting song, but there were few other supporters in evidence. The New York Times consolingly wrote, “‘Small but vociferous’ and ‘made up in noise what they lacked in numbers’ are the conventional terms that might be applied.” An aide asked, “Where are all the people?” Wilson’s greeters admitted that most were lining Pennsylvania Avenue, site of an unprecedented march for women’s suffrage, organized by a brilliant young feminist, Alice Paul.

Five thousand women, many in costume, were led by a young lawyer on a dazzling white horse, Inez Milholland. She wore the costume of a Greek goddess. A throng of perhaps 100,000 men lined the street, many inebriated after inaugural festivities. They heckled, spat, threw objects, and eventually broke through the meager police lines. One newspaper reported that the women “practically fought their way by foot up Pennsylvania Avenue.” More than 100 women were hospitalized. The fracas drew huge national attention. Washington, D.C.’s police chief resigned. Just as at Selma a half-century later, the violence tipped public support toward supporting voting rights. But Wilson still would not budge.

The issue loomed large when Wilson ran for reelection. He spoke at the leading suffrage group’s convention and managed to win applause without actually embracing its position. Young women, in turn, disrupted his State of the Union address, unfurling a banner from the House of Representatives balcony before being hustled off. Republican nominee Charles Evans Hughes backed a suffrage amendment. In the 12 states where women could vote for president, a new National Women’s Party opposed the incumbent. But Wilson still resisted.

Inez Milholland had become a celebrated crusader, tirelessly speaking out for suffrage. At a speech in California, she cried out, “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” She then collapsed at the podium, and was dead within a month. Her funeral was held in Statuary Hall in the Capitol. When Wilson angrily stalked out of a meeting with mourners the next day, pickets began to stand outside the White House for two years. Finally, his hand was forced by the incongruity of arguing for democracy in the Great War while blocking it at home. In September 1918, shortly before the midterm elections, he motored to Capitol Hill with only a half-hour notice, and strode into the U.S. Senate. “This is a people’s war,” he told the senators, “and the people’s thinking constitutes its atmosphere and morale.” (He also insisted, implausibly, “The voices of intemperate and foolish agitators do not reach me at all.”)

***

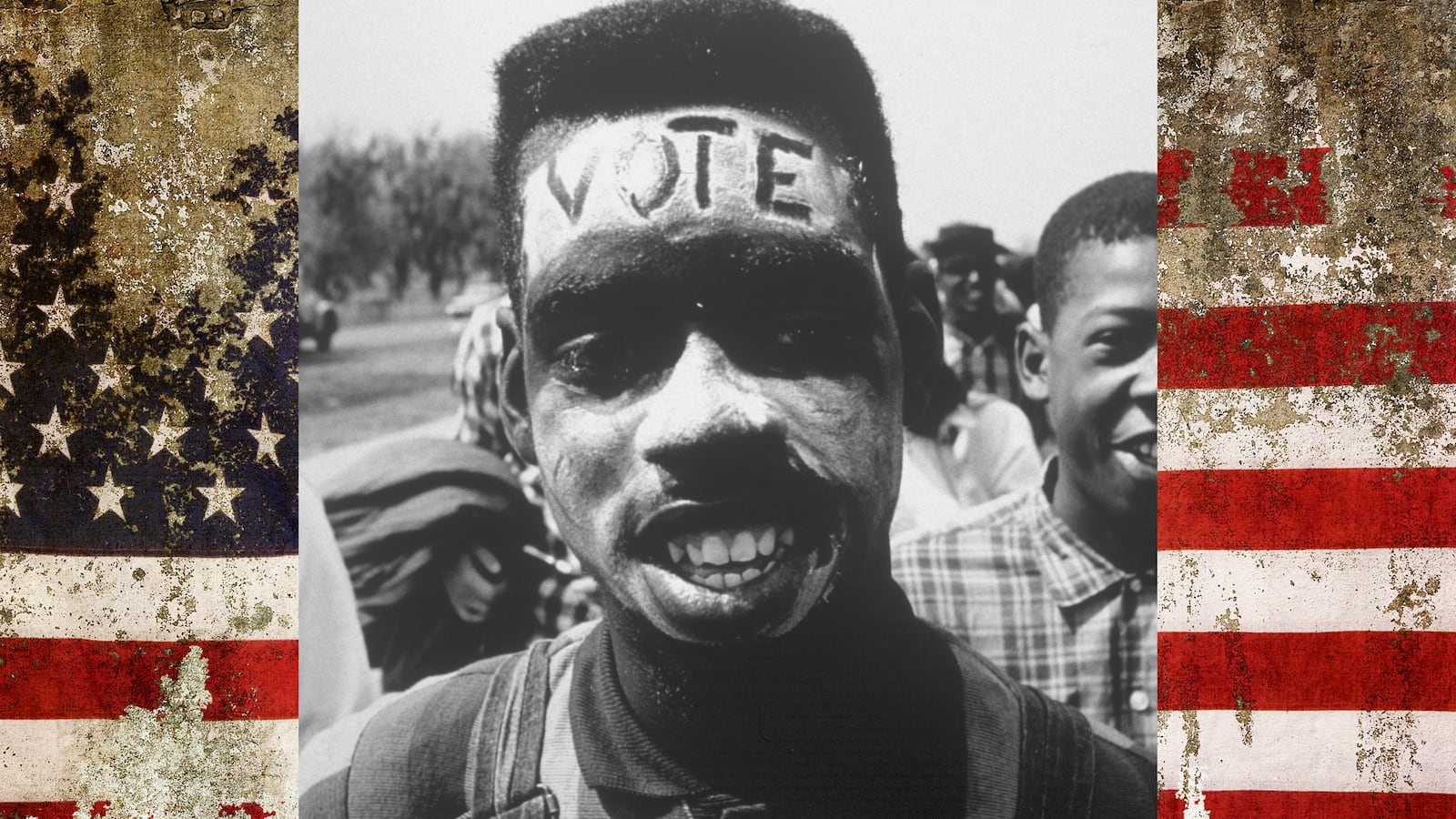

Electoral concerns even loomed over the greatest of all breakthroughs—the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The legislation resulted from the bravery of thousands of Southern black citizens who risked violence and death to protest for voting rights. At the same time, the wary dance between Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon Johnson, two viscerally skilled Southern political leaders, defined the final push.

King and Johnson met and spoke repeatedly in the months before Selma. King would press for a voting rights bill. Johnson would reply, as he did in December 1964, “Martin, you’re right about that. I’m going to do it eventually, but I can’t get a voting rights bill through in this session of Congress.” Eventually Johnson would find himself orating at King about the glories of a voting rights bill when it passed, eventually. “That will answer seventy percent of your problems.” King, for his part, talked about black voting rates and how a surge in voting for Democrats could lead to a “new South.” “Landslide Lyndon” (who had stolen his first Senate election) felt compelled to describe his soaring vision; the moral leader felt compelled to demonstrate his savvy political chops.

Johnson never told King that he had asked the Justice Department to secretly draft a voting rights bill. Soon a quiet deal was struck with the Senate Republican leader, Everett Dirksen, who was known as the “Wizard of Ooze.” King, in turn, never stressed to the president that he was already working to stage a public drama in Selma, Alabama, one of the worst spots for blacks in the South, culminating in the bloody police beatings of John Lewis, Amelia Boynton, and other marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

After the televised violence on Bloody Sunday, demonstrations erupted all over the country. “Rarely in history has public opinion reacted so spontaneously and with such fury,” narrated Time magazine. Johnson let the pressure build to the point where Alabama Gov. George Wallace had to come to the federal government for help. LBJ browbeat Wallace for hours. “Hell, if I’d stayed in there much longer,” Wallace complained, “he’d have had me coming out for civil rights.” Energized, Johnson finally proposed the voting rights bill in a legendary speech before Congress.

The electoral impact was never far from the minds of any of the participants. After signing the Act, Johnson pulled aside the student leader John Lewis, whose skull had been fractured in Selma. Decades later, by then a senior congressman, Lewis recounted his wide-eyed encounter as a 22-year-old. “Now, John,” Johnson told the activist, “you’ve got to go back and get all those folks registered. You’ve got to go back and get those boys by the balls. Just like a bull gets on top of a cow. You’ve got to get ’em by the balls and you’ve got to squeeze, squeeze ’em ’til they hurt.”

African-American voting rates soared in the South. But Johnson was prescient when he told his aide Bill Moyers after signing an earlier civil rights bill, “I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.” The migration of white Southern voters to the increasingly conservative Republican Party became the key political fact of the past half century, realigning American politics.

***

What about today? This election comes after a period when longstanding rules of American democracy have come under intense strain. The modern conservative movement took cues from Paul Weyrich, the founder of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and co-founder of the Heritage Foundation. Weyrich was blunt about his goals in a 1980 speech warming up for Ronald Reagan. “How many of our Christians have what I call the ‘goo goo’ syndrome—good government,” he mocked. “They want everybody to vote. I don’t want everybody to vote.” Over the past 15 years, conservative activists and politicians began a push for more restrictive voting laws. At first the effort didn’t go far; statistically, an individual is more likely to be killed by lightning than commit voter fraud. But demographic pressure built, as turnout by minority voters soared, culminating in the election of Barack Obama in 2008. In 2010, Republicans won control of many state capitols in protest against Obama’s policies and the deep recession. The next year, they passed two dozen laws to make it harder to vote for the first time since the Jim Crow era. Many were blocked by courts before the 2012 election. But the next year, in Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court struck down the heart of the Voting Rights Act. Now 16 states will have new restrictive voting laws on the books for the first time in a high turnout presidential election. Meanwhile, Citizens United and other court rulings upended decades worth of campaign finance law.

It’s been an oddly mismatched debate. Republicans such as John McCain once strongly supported campaign reform. (In fact, in 2008 McCain participated in the presidential public financing system while Obama did not.) George W. Bush signed the reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act. But the Republican Party leadership now lines up against new voting rules and campaign finance laws, even disclosure. Democrats, meanwhile, offered only a tepid response. Obama never introduced legislation to expand voter access or restore public campaign financing, even when his party had a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate.

This campaign, of course, has rattled those presumptions. Will this be another election where fundamental questions about American democracy will be debated in November? It is too early to tell. Voters may be just blowing off steam. Public anger could curdle into simple nationalism and nativism. The self-financing Donald Trump routed the Super PAC-backed Jeb Bush. Or it could be another one of those moments when the parties find their voices debating the basic question of who should have power in America.

If this is such a “democracy moment,” it will not be the last one. As John Adams understood, “There will be no end of it.” Let’s hope so.

This article has been adapted from the book The Fight to Vote, published this week by Simon & Schuster. © 2016.