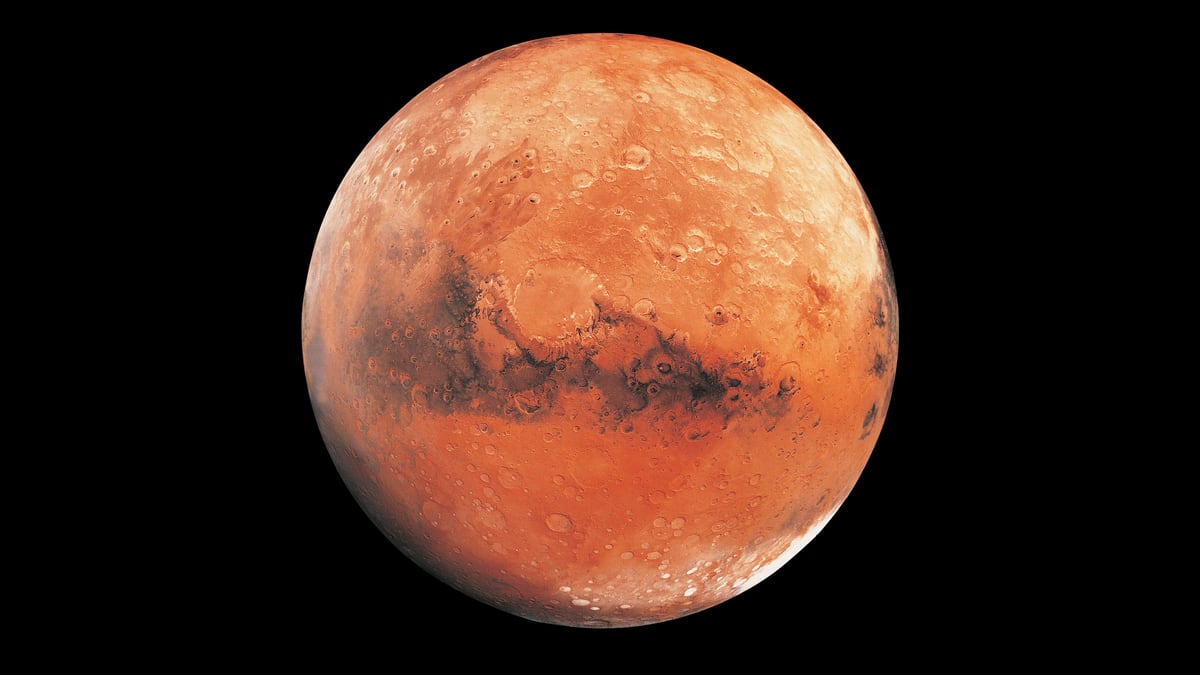

NASA is on a mission to understand what lies beneath the surface of Mars. There could be evidence of long dried-up water. There could even be signs of bacterial life.

But the self-digging Mars InSight robot that the space agency deployed to the Red Planet back in November 2018 has a problem. InSight’s jackhammer-style “mole” probe keeps popping out of Mars’ sandy surface, befuddling scientists overseeing the probe mission from 160 million miles away.

Now NASA has a surprisingly simple plan to help shove the mole back into alien dirt. It commanded the probe’s spaceship-like lander to extend a robotic arm and give the mole a little shove.

The robotic assist could be the turning point in NASA’s high-stakes mission to understand what lies beneath the Martian soil. And it’s a reminder of the ceaseless ingenuity of agency scientists who constantly confront weird new problems while remotely exploring alien planets millions of miles from Earth.

Mars InSight is one of several scientific missions probing the Red Planet—and the first to focus on the planet’s interior. The $830 million probe, built by Lockheed Martin, weighs 800 pounds and includes two solar panels, a bevy of sensors including the jackhammer mole, and a robotic arm that’s more than 5 feet long.

NASA deployed the probe to Mars in the hope of understanding the 4 billion-year-old planet’s distant past. The data could point toward alien life.

“By some estimates, roughly half of the biomass on Earth might be made up of bacteria living very deep [several kilometers] underground,” Matthew Siegler, a member of the mission’s science team, told The Daily Beast. “So InSight’s experiments can provide better estimates on the deep ‘habitable zone’ below Mars’ surface where past or even present liquid water could have existed, potentially supporting Martian bacteria.”

But getting good readings meant going underground. In late February 2019, NASA commanded InSight to deploy its mole. The device was supposed to bury itself 10 to 15 feet underground. In tests on Earth, the whole burrowing process took just 20 minutes.

On Mars, it didn’t work at all. “Mars threw us a curveball,” Siegler said.

“What we observed on Mars was an initially rapid descent followed quickly by a complete cessation of downward movement,” Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer on the InSight team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, told The Daily Beast. “This kicked off a long series of investigations into possible causes and potential solutions.”

The scientists guessed that maybe the mole had hit a patch of thick “cemented” soil. So they directed the self-hammering ’bot to just keep hammering and try to punch through.

That didn’t work. And by June 2019 the NASA team was getting desperate. The scientists extracted the mole’s support frame from the dirt, exposing the main part of the mole and the pit surrounding it.

The pit was particularly interesting to Hudson and the team. Never before had anyone dug a hole on Mars and peered inside. The scientists spent weeks analyzing the pit. “By mid-summer we had reduced the probable causes to two options: the mole tip had hit a large rock, or we had less friction than required from the soil surrounding the mole,” Hudson explained.

In other words, the Martian dirt might be sandier than they expected.

That was the best-case scenario. “If it were a rock we could do nothing about it—the mole would be dead,” Hudson said. “But low friction is a more subtle issue and presented a possibility to help the mole with the arm.”

While the team in California mulled strategies for getting the mole moving, other sensors on the InSight lander were gathering incredible results. After analyzing data from the probe’s seismic sensors, NASA researchers in February announced they had detected, for the first time, earthquakes deep inside Mars.

“This is generally good news for possible life on Mars, because seismic activity would imply that there is still liquid magma underground that is moving, and with this the possibility of volcanism even today,” Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at the Technical University Berlin, told The Daily Beast.

“The sites of active volcanism are, of course, also top sites where we should look for life, especially in a cold and dry place such as Mars—because these would be the locations where we would expect higher temperature and the availability of liquid water, possibly the last refugia of life from a time period long ago when Mars was warmer and wetter, and life more widespread.”

In late summer 2019 the InSight squad came up with a plan to jumpstart the stalled underground sensor. They pressed the shovel at the end of the lander’s robotic arm against the side of the mole and pushed. The pressure from the shovel had the effect of pinning the mole to the ground and increasing the friction between it and the soil. “And it moved!” Hudson recalled.

InSight was back in business. Soon the mole sensor was almost entirely underground.

Then on Oct. 26, the mole popped out. The scientists in California pinned the ’bot again. It dug for a few weeks… then popped out on Jan. 18. “Mars surprised us again,” Hudson said.

It was time for a fresh approach. NASA has a plan. But it’s risky. “We are angling to push on the back cap of the mole with the scoop edge,” Hudson explained. This is risky because the mole is tethered to the main lander by way of delicate wires snaking out of the back cap of the underground sensor.

Cut the wires and you kill the probe. It’s on Hudson and his team to carefully maneuver the robotic shovel-arm to within inches of the mole’s life-giving tether and apply just enough downward force. Move too far too fast, and NASA could jeopardize a nearly billion-dollar set of equipment and years of work.

Will it work? Hudson and his team should know soon.

Even if it doesn’t, InSight isn’t a total waste. The mission’s detection of seismic activity alone has thrilled scientists. And if the robotic push ends up breaking the mole, NASA will at least have learned an important lesson.

“You can’t accurately predict what a planetary surface will behave like until you’re at that specific surface,” Hudson said. “When we have the opportunity to send another geophysical probe to Mars, we would need to broaden our test program to include cemented and crusted soils as well as loose.”