In 1957, the state of Louisiana built a four-lane vertical lift bridge on North Main InfoClaiborne Avenue over Industrial Canal, streamlining access from New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward, a vast semi-rural area of mostly poor people. That year, two African American evangelists moved downriver to the Lower Nine, and Sister Gertrude Morgan became a Bride of Christ. She wrote:

He has taken me out of the black robe and crowned me out in white.

We are now in revelation, he married me, I’m his wife.

For some 18 years, Sister Gertrude Morgan and Mother Margaret Parker had harbored cast-off children as missionaries in the city proper. Anchored in evangelical Christianity, Sister Gertrude gave Bible lessons to neighborhood kids in the house at 2538 Alabo Street she shared with Mother Margaret. Discovering her identity as a heavenly bride, and the impact of divine messages, so consumed Morgan that she began crayon drawings, scenes of her early life, which unloosed a torrent of paintings on varied surfaces, bursting with colors and figurative renderings of earthbound folk and angels, white-robed and white-winged, swirling across the sky; churches with choirs in gowns swayed like windswept wheat stalks beneath a city in the clouds—the New Jerusalem as promised in Book of Revelation. As the scriptural account of angels and demons battling for salvation, Revelation inspired the pencil-written passages on many of Sister Gertrude’s paintings, which convey visual chapters of her spiritual odyssey.

Gertrude Morgan was a mystic, a soul in direct communication with God. In that, she resembled St. Catherine of Siena and William Blake, poetic minds charged by visions of intimacy with the Lord. No other figure of New Orleans history approaches her in this regard.

“Sister Gertrude Morgan was a self-appointed missionary and preacher, an artist, a musician, a poet, and a writer possessed of profound religious faith,” writes William A. Fagaly, a New Orleans Museum of Art curator for many years who helped organize a 2004 retrospective on her work for the American Folk Art Museum in New York. Her paintings, which hang in many museums and command substantial gallery prices, follow her life in settings of worship and celestial realms, as in “Jesus Is My Airplane.” Her images often feature such written reflections as: “This is the lord’s wife speaking to you Christ is talking to you through me. You just well take heed and make up your mind and say, lord, let it be.”

As her thought field bloomed with sacred images, Sister Gertrude made regular trips into the sinful city to preach and sing on Royal Street. She was soon swept into currents of a jazz renaissance, the civil rights movement and a dynamic gay culture, breaking shackles of bigotry. These changes charged the work of her most prolific years.

Born on April 7, 1900, Gertrude Williams was the seventh child of Frances and Edward Williams, a farming family in LaFayette, Alabama. The family moved several times. In 1920 Gertrude was living with her mother and three siblings in Columbus, Georgia, working as a domestic. “Gertrude apparently did not receive schooling beyond the third grade,” writes Fagaly in Tools of Her Ministry, the catalog for a 2004 museum retrospective. “It is unclear why her education ended at such a young age... but it’s possible she had a learning disability or behavioral problems; she stated later that she ‘was a peculiar little person in childhood days.’”

A collection of her writings, mostly on notebook paper, which surfaced after Fagaly’s groundbreaking research, suggests that her ability to write improved in her sixties as she copied out long passages of scripture. Her earlier, stream-of-consciousness prose pinpoints how she encountered a spiritual presence, as a working 14 year old, apparently without great exposure to church: “In going to my work one morning I was hearing girls talking about they got Religion. The lord put it in my mind to ask him lord teach me how to pray and what to pray for. For Jesus sakes so many sweet words came into my heart until I found my way after three days of being in pray an angel begin to sing to me… God put it into my mind to tell some of the history of my life that someone may make up their mind to come out of darkness into this marvellous light.”

Many years later she painted scenes of Rose Hill Memorial Baptist Church in Columbus, Georgia, which she attended as a young woman. The pictures she made in New Orleans of those early years, in acrylic and pencil and ink, evoke the harmony of a pastoral village, a starting point for her journey of the spirit. In 1928 she married Will Morgan in Columbus; she enjoyed “goin’ to the picture show and I liked to dance.” She did a quaint picture of their house but no image of Will. In 1934 she had a revelation.

The strong powerful words he said was so touching to me

I’ll make thee a signet for I have chosen thee

Go ye into yonders world and sing with a loud voice

For you are a chosen vessel to call men, women, girls

And boys.

That experience would be a heady rush for anyone; a woman so galvanized might well be challenging for any husband. She wrote nothing on why or when she and Will parted ways.

After a brief return to Alabama, working as a domestic, a revelation on February 26, 1939, told her to keep on the holy path in service of the Lord. And so she set out on the road. For an itinerant black evangelist wending her way through the Gulf South during the Great Depression, where better to bear witness than the Babylonian city of New Orleans? She later called it “the headquarters of sin,” a view harbored by upstate politicians and people in Pentecostal woodlands that hatched the televangelist Jimmy Swaggart, an anti–New Orleans mentality still strong in rural Louisiana and likely to remain so. The city resembles tropical ports like Havana or Veracruz more than Shreveport or Baton Rouge.

Sister Gertrude Morgan arrived in a time of tumultuous urban change, four years after Senator Huey P. Long’s 1935 assassination in the towering Art Deco state capitol he had built in Baton Rouge. Federal agents were hunting down custodians of the Long machine. “When I took the oath of office, I didn’t take any vow of poverty,” Governor Dick Leche asserted in 1939. People believed him. Leche followed a parade of officials and bottom-feeders into federal prison. Huey’s younger brother, Lieutenant Governor Earl K. Long, succeeded Leche, declaring, “I am determined to remove from the seat of authority every man who in any degree worships Mammon rather than God.” It is a struggle in which the most charitable historians would consider Mammon to have the upper hand today

Long’s hostility to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his plan to challenge FDR in the 1936 election did not deter Robert Maestri’s ambitions. Born in 1889, a son of Italian immigrants, Bob Maestri saw his father make money in real estate for Storyville, the bordello district. Despite a third-grade education, Bob prospered with the furniture store he inherited and invested heavily in real estate. Maestri thought nothing of a $50,000 “loan” to Long’s 1927 gubernatorial campaign, knowing it would never be repaid. Long won. As commissioner of conservation, Maestri allowed oil companies to exceed production quotas in exchange for funds to fuel the Long machine. Long waged war with New Orleans ward leaders, the Old Regulars, for failing to support him early and with Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley for backing a failed attempt to impeach him.

Long slashed support for the city in retaliation. By the early ’30s, civic leaders were promoting New Orleans as a tourist destination as it lurched toward bankruptcy. After Huey’s death, Governor Leche and Lieutenant Governor Earl Long pressured Walmsley to resign. Maestri qualified for mayor in a special election. Unopposed, he won without a vote cast. Mayor Maestri mended fences with FDR. In a lunch at Antoine’s Restaurant, over oysters Rockefeller, he asked the president, “How ya like dem ersters?” The rough-hewn Maestri, whose furniture store sold beds to bordellos, put New Orleans in line for 1937 U.S. Housing Act funds to build six housing projects. By the ’60s, all of the projects housed poor blacks.

As lakeward growth accelerated, the Sewerage and Water Board extended pipelines into areas designated for white residents in Lakeview. New Orleans embraced the American myth of endless space with thousands of swamp acres drained, trees cut, and bush flattened to graft streets and create neighborhoods. Developers’ publicity erased any concern over a stable urban grid. Without the interior cypress wetlands, the city began, very slowly, to sink. “By the ’30s, Lakeview’s drained land had subsided, causing street pavements to break apart,” writes John Magill. The problem worsened over time.

Mayor Maestri personally paid to put a wooden floor in a black Gentilly church, among other acts of personal philanthropy; he worked the federal spigot to build a new Charity Hospital, an Art Deco giant on Tulane Avenue. He shrugged at French Quarter prostitution, the spread of slot machines, and the exposé of a bookmaking operation in a precinct station. As crime and police corruption ran rampant, writes Anthony J. Stanonis:

“Beautification programs abounded. Workmen, many of them from the WPA [Works Progress Administration], planted live oaks, azaleas, and flower plants on the medians of almost every major thoroughfare within city limits. Under Maestri, more than 76,000 families and businesses signed a pledge to gather garbage from the streets, while a modernized Department of Public Works efficiently collected the refuse. On Maestri’s watch, the city added 150 trash receptacles to the business district and improved conditions at the garbage dumps, notorious for emitting foul odors that wafted into the French Quarter and the central business district.”

In the mid ’40s, Tennessee Williams lived at 630 St. Peter Street, where he wrote A Streetcar Named Desire. The city, with its elegant patina, grand foodways, Carnival season, and raffish charms, was ever the melting pot, which featured in the ads that the Convention and Tourist Bureau placed in national magazines to attract tourists. In 1946, Maestri faced DeLesseps (“Chep”) Story Morrison, a young attorney of old pedigree. He won a seat in the legislature before the war and while an Army colonel in Germany was reelected in absentia thanks to his wife’s campaigning for him. After the war, Maestri had grown distracted, and the city shabbier, when Chep Morrison, with movie-star looks, announced for mayor, promising reform. He had a brigade of Uptown ladies with brooms symbolizing clean-up needs, Times-Picayune editorial support, and black ministers seeking better prospects for African Americans. In a scene worthy of a Tennessee Williams play, the 33-year-old glamour candidate told a secret meeting of pimps, hookers, and taxi drivers that he would not upset their sub rosa economy. Morrison won; he made the cover of Time as a modern Southerner. The economics of segregation hit blacks hard, pushing them deeper into poverty.

In 1940 Sister Gertrude was living with two other evangelists at 816½ South Rampart Street amid taverns and fast life outlets. The residence had “no fewer than 17 children under 17, two boarders and three women to run the ‘household,’” the scholar Elaine Y. Yau writes in a probing account of Morgan’s career. Sister Gertrude was listed as an assistant, along with Cora Williams, to Margaret Parker, the head of the household. The women were classified as “missionaries” caring for orphans. How Morgan joined the other Sanctified women we do not know. They moved the orphanage from Rampart to the Irish Channel along the river and moved again before the 1942 purchase of a large house at 533 Flake Avenue in Gentilly Woods, surrounded by small churches near Elysian Fields in the Seventh Ward. Sister Morgan helped with the down payment. “What is most striking amid the formal legal language is their economic independence as women,” continues Yau. “As one notary commented upon the situation, the funds used for the purchase ‘were acquired by them through their own business efforts.’”

New Orleans was like a foreign country compared to the rural towns of Morgan’s past. In the ’40s, Elder Utah Smith had a warehouse church, the Two-Winged Temple in the Sky, which held 1,200 people near the Calliope Street housing project in Central City. Wearing the feathered wings of a seraphim, Elder Utah Smith played the electric guitar as he sang, pranced, and preached. He too was a survivor. Abandoned by his mother, raised by a grandmother in bleak poverty near Shreveport, Smith hurled himself into popularity through performances of rebirth. From an early advertisement for a Shreveport revival: “The main feature of the program—Rev. Utah Smith will dramatize a Bible demonstration—the Resurrection of Lazarus. He will raise a real man out of the casket.”

For his signature song, “I Got Two Wings,” Smith in his wings of a seraphim would attach himself to cable wires and swing out over the stage, flying back and forth, playing the guitar and singing, his energy radiating to the worshippers in a spectacle beyond anything they had ever seen in sacred space. Smith drew attention in the New York Times, and eventually performed at the Museum of Modern Art.

Elder Utah Smith’s singing sermons in New Orleans began airing on WJBW radio in 1944 and moved to another station with revival meetings through 1953—a soundtrack to Sister Gertrude and her two cohorts, raising homeless children in the two-story house they purchased in Gentilly Woods. They collected donations by visiting “Holiness” congregations, or Church of God in Christ. Radio broadcasts influenced evangelists to go outside in the spirit of Psalm 98: “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord.”

In Morgan’s painting of the Flake Avenue home church, a man plays guitar next to an altar, as congregants sit in robes with Sister Gertrude at the drums—she was making music before she began to paint.

Another picture, “The Flake Avenue Orphanage Band,” has three black-gowned women next to a drum set, an upright lady who resembles Sister Gertrude, tilting with a tambourine, and dressed-up young women arrayed behind the sanctified ladies.

“God married me himself around 1942,” she would write. “When I learned I had become his wife I was so happy back in those days. Being young in the cause. O I didn’t no what to do. But as the days weeks months and years rolled by I began to see greater light, and more of God’s mystery see. What great love Jehova had for little me.”

Her writings do not say whether she confided in Margaret Parker or Cora Williams about the 1942 revelation. Did she announce it at services or keep it secret until the years when she began to write? The many scriptural passages she wrote by hand starting in the late ’50s suggest that her literacy came from immersion in scripture. It was in 1957, after Cora Williams’s death, that Sister Morgan and Mother Parker found the house on Alabo Street in the Lower Nine, the same year she had the revelation of herself as bride to both God the Father and Jesus the Son.

The Lord of Hosts made himself known to me in my work through and through

When he crowned me out he let me know I was the wife of my Redeemer, too

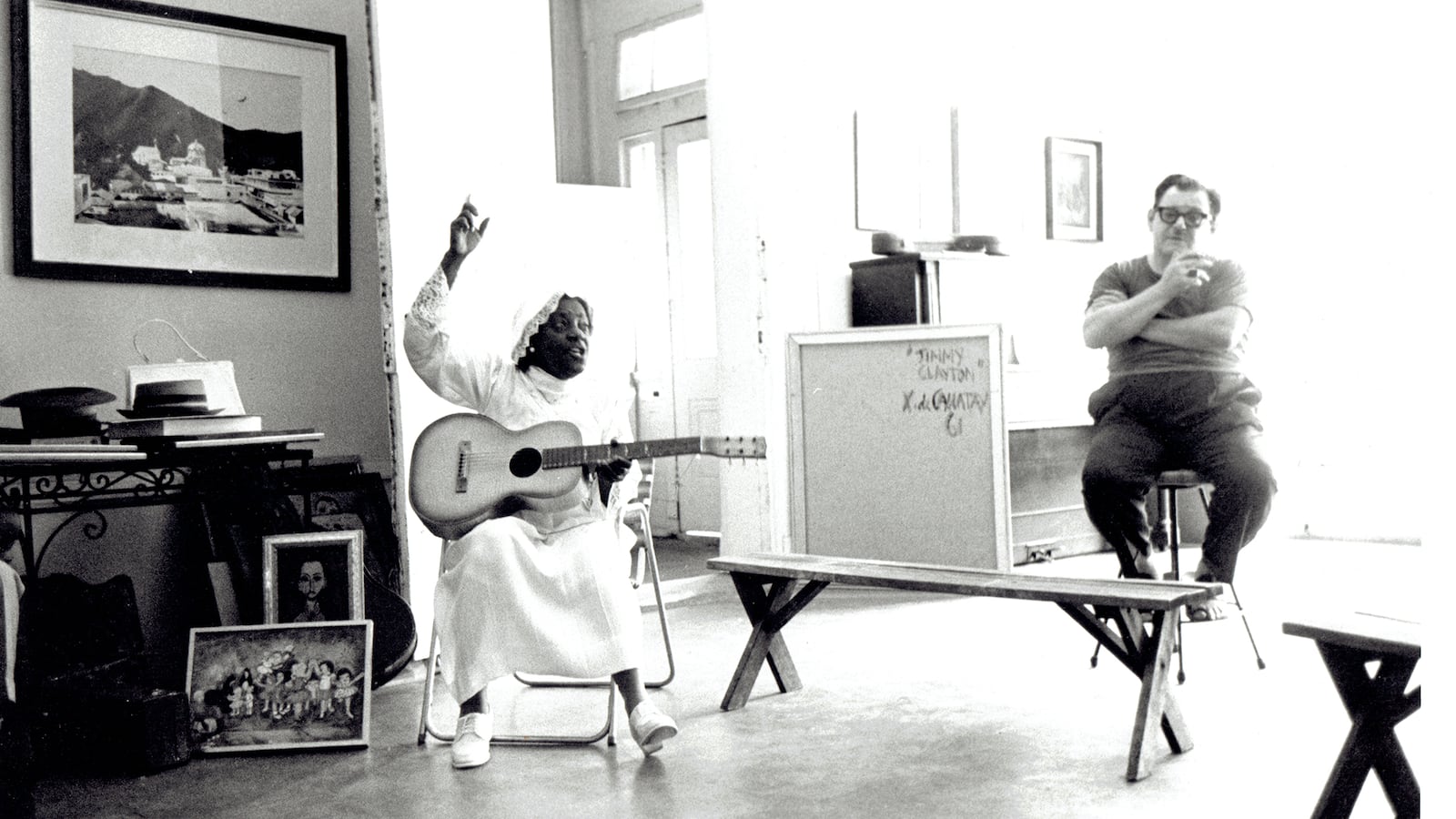

This period ignited her artistic output. She replaced the black dress of child-fostering missionary years with bridal white, resembling a nurse’s garb. In the late ’50s, she began singing on French Quarter corners, playing the guitar and tambourine, and selling her paintings, for even missionaries must pay bills. One day her work caught the eye of a portly art dealer with thick horn-rimmed glasses, who wore rumpled T-shirts and chain-smoked unfiltered cigarettes. Larry Borenstein was an unlikely redeemer.

Folk art was barely at the margins of high culture when Borenstein, moved by her naive lyricism, offered to exhibit Morgan’s work at his Associated Artists Gallery at 726 St. Peter Street. They were the oddest couple in an enclave of artists, rebels, and a gay culture spreading its wings despite rough cops and Mayor Morrison’s 1958 crackdown, with arrests at places known for gay patrons.

The French Quarter was not a milieu accustomed to a spouse of the Almighty; but it welcomed all comers, and Gertrude Morgan, on the cusp of 60, was an adventurer. After being poor all her life, she had her paintings selling in an art gallery. Picture her as she walks along Royal, Chartres, and the streets near Jackson Square, taking in the myriad artistic styles displayed in other windows of galleries that abounded in the old city core. The journey from Alabama and Georgia had taken her into a realm she never imagined. Noel Rockmore, a seasoned painter who exhibited with Borenstein, drank hard, chased women, and painted a portrait of Sister Gertrude. He did a drawing of her face. Her writings do not dwell on Rockmore or the bohemian ruckus in this new world of the city.

Borenstein had no use for religion, least of all Christianity. But in his breadth of life experience he realized that Gertrude Morgan was pure; she had a sacred essence that made him protective, hoping to help her. Borenstein made money at nearly everything he tried. “The sound of a cash register is like a Jewish xylophone,” he joked to a friend.

Born in 1919 in Milwaukee, Lorenz Borenstein came from a family of Russian Jews, his father a merchant. Larry left home at 14 to work in a sideshow at the Chicago World’s Fair but returned to finish high school in 1938. Along the way, he sold magazine subscriptions and cleared $15,000 in nine months, huge money in the Depression. He attended Marquette University but left before graduation, working for a time as a reporter. He landed a job in Florida with a tourism promotion enterprise. Passing through New Orleans in 1941, he liked the rainbow of peoples, the Old World ambience, and he decided to stay.

The city’s small Jewish community gave great support to the museum, symphony, and major causes, despite the anti-Semitic exclusions by Comus and several other elite Carnival krewes with debutantes as queens and maidens of the balls. In a 1968 piece for the New Yorker, Calvin Trillin noted that wealthy New Orleans Jews took vacations during Mardi Gras, while homosexuals poured into town.

“For gay men in the South especially, New Orleans was a mecca, a sacred city, mentioned in hushed tones and awe, even among those Southern Baptists who despised its blatant hedonism,” writes Howard Philips Smith in Unveiling the Muse. “Gay bars in the French Quarter were allowed to prosper as long as they made their payoffs to the police and the mob… On Shrove Tuesday, however, the most flamboyant and creative costumes could be seen parading around the narrow streets.”

Borenstein made friends with Miss Dixie (Yvonne Fasnacht), a lesbian and bulwark of the gay community who provided a hub at Dixie’s Bar of Music across Bourbon Street from his spacious second-story apartment. He made money trading rare stamps, running a bookstore, and speculating in foreign currencies. With so many struggling painters around him, Borenstein became an art dealer. He also became a realtor and said that he bought his first building in 1957 for $32,000, all borrowed; he slowly became one of the largest property owners in the Vieux Carré.

“Larry hung out at Bourbon House at the corner of St. Peter,” says JoAnn Clevenger, the grande dame of the Upperline Restaurant, filled with the paintings she began collecting in her salad years as his neighbor.

“Tennessee Williams was a regular at Bourbon House; so was Lee Friedlander when he visited, and local artists like Noel Rockmore,” Clevenger says. “People involved in gambling went there—they weren’t really Mafia, they wouldn’t put a price on your head, they were just running numbers and calling in bets on the telephone. The place had entrances on Bourbon and St. Peter. The bar had two sides, one gay, one straight. The cashier served both sides. There wasn’t any regulation, people hung where they hung. Tennessee Williams liked to visit the straight side, listen to the jukebox, and have a Brandy Alexander. He was quiet. People were reverent, they wouldn’t go up and introduce themselves. His cousin introduced us; her name was Stella, like the wife in Streetcar.”

“Most of the antique dealers I knew were gay,” continues Clevenger. “The My-O-My Club out by the lake had female impersonators. A lot of them lived in the Quarter. Larry lived diagonally from Bourbon House, a big place with a wrap-around balcony. He gave Mardi Gras parties and wore a black cape and black hat.”

Borenstein also specialized in pre-Colombian art at his St. Peter Street gallery, Associated Artists. He got thrown in jail in Mexico three times for excavating artifacts. “In the U.S. government’s zeal to stop marijuana coming across the border, they funded checkpoints for the Mexican government and it became no longer possible to slip the guard a few pesos when he was looking through your car,” he later told the writer Tom Bethell. “In 1969, it cost me a great deal of money to get out. They confiscated my Buick station wagon and its cargo, plus I had to pay a large cash bribe to get out.”

Borenstein also had a softer, enlightened side. He invited jazzmen to the gallery for jam sessions when race-mixing was illegal. In 1957 police hauled several musicians before a judge who called the trumpeter “Kid” Thomas Valentine a “yard boy,” told him not to get “uppity,” warned a visiting white trumpeter not to “mix your cream with our coffee,” and then dismissed charges. Borenstein thought the music would increase traffic to the gallery. With police bribes at gay bars a fact of business in the Quarter, Borenstein probably paid cops to hold back.

The 700 block of St. Peter and surrounding streets formed a counterculture ground zero. Born in 1941, JoAnn Clevenger (née Goodwin), was raised a Southern Baptist in upstate Rapides Parish; she moved to New Orleans in high school, with daily visits to Charity Hospital as her mother slowly died of cancer. In 1960, at 19, she married Max Clevenger, 31, a technician at LSU Medical School. Max was close with Dick Allen, who lived minutes away, a Tulane graduate doing oral history interviews of jazzmen with Bill Russell under a Ford Foundation grant for Tulane’s embryonic William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive. Clevenger recalls this period:

“We lived above Dorothy Rieger’s Restaurant on Chartres Street. She had a grand piano. Singer Frankie Ford and music people would stay up till all hours singing opera and show business songs. Here I am 19 years old, I’ve practically been living at Charity Hospital, my mother just died, I’m pregnant and all this exotic stuff is going on downstairs. Dottie Rieger was a role model for me because she had this restaurant, we each had red hair and hers was piled up just like mine is now. From our apartment balcony I watched the ladies going to the La Petit Salon in hats and white gloves; then the ladies of the night, the streetwalkers; and on Sunday morning, the people going to church at the Cathedral and you would see s at the Morning Call having coffee. The nuns had such mystery for me. Caroline Dureaux the artist captured their habits silhouetted against buildings of the French Quarter so beautifully. Growing up, my perception of New Orleans was that the people there were not very nice, did whatever they wanted and the priests forgave them. The Bourbon Street bus carried students at the convent school. Seeing those girls in their uniforms, and those green eyes and amazing variety of skin colors—it was very exotic to me, because growing up in central Louisiana, the schools were all segregated, you didn’t come across black people hardly at all.”

The school, St. Mary’s Academy, run by Sisters of the Holy Family, an African American order cofounded by St. Henriette Delille, was damaged in 1965 during Hurricane Betsy and moved to another location.

Bill Russell sat at Borenstein’s jam sessions, a balding, mild-mannered man whose shop across the street sold jazz records; he stacked his vast research on tall shelves in a nearby apartment with barely room for a bachelor’s bed. Born in 1905 in Ohio, educated at Columbia and the University of Chicago, Russell the violinist composed avant-garde percussive music before he discovered jazz, and then he could never get enough. The author of three chapters in the influential 1939 anthology Jazzmen, Russell was a catalyst in the New Orleans Revival of the ’40s; he guided the comeback of trumpeter Bunk Johnson, a star of Armstrong’s youth, recording the old man with George Lewis, whose quavering clarinet solos melded sorrow and sweetness in equal measure.

The New Orleans Revival was equally a product of New York, Chicago, San Francisco, London, and Paris, where jazz aficionados, writers, and producers, keen to the music of established artists, wanted more of the root sound. As Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Red Allen, and others long gone from the Crescent City found quickened interest in the early music of the parades, churches, and fleshpots where they developed their chops, a fountain of possibilities opened for “the mens,” as the players in New Orleans called themselves, seasoned jazz musicians who had never left.

“Time after time, we saw men who had been laid low by diabetes, strokes, emphysema, alcohol, and just plain old age climb from their sick beds, like Lazarus, and live to play again,” wrote the clarinetist Tom Sancton in a riveting memoir, Song for My Fathers. Sancton, who was taught as a teenager by George Lewis, went off to Harvard, to Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship, and then to a career as a journalist based in Paris. After Hurricane Katrina, he returned to New Orleans to teach and look after his ailing parents. He plunged into collaborations with jazz pianist and bandleader Lars Edregan, a Swedish transplant who had lived in New Orleans for many years. Sancton’s lyricism on the title cut of City of a Million Dreams (2012) pays homage to the composer and clarinetist Raymond Burke (1904–86), a son of the Irish Channel and stalwart of New Orleans Style.

Rhythm-and-blues was the commercial sound of the day. Fats Domino, who sang with a honey-sweet baritone over a rolling boogie piano, built a palatial house in the Lower Nine, riding a wave of records that got white teenagers dancing before Elvis. For jazzmen who stayed after the diaspora, the Depression was severe and the postwar years a grind. With limited venues, most musicians had to take day jobs.

Sister Gertrude had been selling pictures a short block from Mammon’s lap on Bourbon Street when Borenstein took her as a client; the sales gave her the uninterrupted stretches to work that every artist needs. The condemnations of evil or Lucifer lace the handwritten lines of her pictures, with nothing on strip clubs or the fallen world on Bourbon Street. She was adjusting to daily encounters with white people, some of them strange, most of them nice. She saw the world through a scriptural prism, God’s battle with fallen angels.

Lower Bourbon Street’s neon strip had a few venues that featured bandmaster Oscar “Papa” Celestin, Dixieland stars Pete Fountain and Al Hirt, and the stately sunflower of Galatoire’s Restaurant. But most of lower Bourbon had a tawdry tenor of fading vaudeville and was synonymous with strip clubs, joints like Stormy’s, Silver Frolics, Gunga Den, and the Sho-Bar, where Governor Earl K. Long in 1959 fell for the ultrabuxom Blaze Starr. Uncle Earl, as he was known, squired the 23-year-old Blaze around before his last hurrah, a 1960 congressional race in central Louisiana. He sent her off to Baltimore for the campaign, out of sight, out of mind, in an era before saturated media. Long won with a strong Pentecostal vote and died nine days later.

Some strippers danced to live music played by black musicians behind a curtain, unable to see the women, giving no scandal to white men ogling the female bodies. Evelyn West was touted as “Biggest and Best, the Girl with the $50,000 Treasure Chest Insured by Lloyd’s of London.” Bebop saxophonist and bandleader Al Belletto recalled a New Year’s Eve “with a dead guy in the dressing room… they weren’t going to notify the police until all that good business had come in and gone.”

In 1960, Borenstein let a California jazz enthusiast, Ken Mills, use the patio behind the gallery at 726 St. Peter Street for recordings that included Ernie Cagnolatti on trumpet. In March 1961, Mills and a gung-ho jazz maven named Barbara Reid, who lived with her husband Bill Edmiston and their infant daughter, Kelly, in a flat above the gallery, formed the Society for the Preservation of Traditional Jazz with Bill Russell. As the music salon developed legs, Allan and Sandra (Sandy) Jaffe, a young couple from Philadelphia, moved to New Orleans, following the music’s magnetic pull. Enthralled by a parade that featured Percy Humphrey on trumpet and Willie Humphrey on clarinet—Allan had the Humphreys’ records!—the Jaffes followed the crowd to an art gallery on St. Peter to hear more music.

Born in 1935, Allan Jaffe grew up in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, and attended Valley Forge Academy, playing tuba on a music scholarship. His grandfather had played French horn in the Russian Imperial Army; his father played mandolin. In 1957 he graduated from Wharton, the University of Pennsylvania’s elite business school. Allan and Sandy were elated to be in the city where jazz began. At the gallery jam session they met Larry Borenstein, an avuncular Jewish soulmate eager to help them put down roots.

As the friendship grew, Borenstein shared leads on Quarter real estate. Allan Jaffe had financial smarts balanced by a joy for music, and a growing affection for musicians like the trumpeter Punch Miller, the Humphreys, trombonist Jim Robinson, the supreme George Lewis, and other players he got to know from the jam sessions.

Meanwhile, Borenstein’s life took a dramatic turn. Divorced since the mid ’50s, Larry fell in love with Pat Sultzer, a willowy, dark-haired beauty of 18, reeling from her parents’ divorce. She was a part-time student at Louisiana State University in New Orleans, and a waitress in Quarter bars, when she was raped and found herself pregnant, with no way to identify the father. With a rescuer’s tenderness, Larry proposed marriage; he wanted to raise the baby with Pat. She feared that Larry, though soothing in the moment, would be unable to love a child not his own. She entered a home for unwed mothers, gave birth to a girl, and, after six weeks of nurturing, allowed a childless couple to adopt the baby.

Borenstein’s complex personality was at a crossroads of midlife. The art manager for a 60-year-old black woman who considered herself a bride of Jesus was opening his heart to a woman young enough to be his daughter. Larry had his own vulnerability, a hunger to be loved. Pat responded with blazing reciprocity.

Larry Borenstein entrusted Reid and Mills to supervise the upstart jam sessions, which were attracting growing crowds, and left on a buying trip to Mexico. He was gone so long people wondered why. Several friends later speculated that he had been put in jail for digging up antiquities. When at last he returned, Borenstein decided to move his gallery next door and let the music hall operate at 726 St. Peter.

In the summer of 1961, Pat traveled to Eureka, California, to visit her mother. Nineteen now, she sent word to Larry that she was carrying his child. “I am glad you are pregnant and I’m looking forward with as much enthusiasm as you are,” he wrote her on May 28, 1961. He drove out to Eureka with Bruce Brice, a young African American who was learning to paint with a day job making frames for Borenstein’s gallery. The car broke down in Baton Rouge; they had to sleep in separate hotels because of segregation laws. Once the car was repaired, they headed west. Brice, who went on to a successful career as a folk artist focused on funerals, parades, and New Orleans neighborhoods, stayed behind in Encino, California, painting the house of Larry’s sister and brother-in-law. Larry and Pat, meanwhile, married at a Buddhist temple in San Francisco.

After the honeymoon, Borenstein fired Reid and Mills, who had worked tirelessly to launch the Slow Drag Hangout. His brusque move left Reid feeling bitter; but Larry couldn’t see two idealists running a business, and if the music didn’t pay for itself, he’d have to swallow losses before pulling the plug. He was confident in Allan with his Wharton degree. The renamed Preservation Hall opened in the fall of 1961 with rustic benches, no beverage sales, no cover charge (donations welcome), and classic jazz for people of all ages.

Preservation Hall began as the city was jolted by national coverage of crowds screaming at four black girls, escorted by federal marshals into two Ninth Ward schools, emptied of white children.

Governor Jimmie Davis, the country-western singer famous for the hit “You Are My Sunshine,” resorted to unconstitutional devices in trying to thwart the city’s public-school desegregation. Davis was a cipher for Leander Perez, the overlord of St. Bernard and Plaquemines parishes downriver. A firebrand White Citizens Council leader, Perez is a creature of history worthy of Dante’s Inferno, a titanic bigot who swindled a fortune from mineral-rich public lands under his control, systemic theft at that time unknown. (After his death, Perez’s heirs settled by returning $10 million and 60,000 acres to the public.) When Governor Davis failed at “interposition,” the state usurping school board powers to blunt a federal court order, Perez railed at a conspiracy of “Zionist Jews” and whipped up a crowd at Municipal Auditorium: “Don’t wait until the burr-heads are forced into your schools. Do something about it now!” A white mob outside City Hall made more national news, bellowing, “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate!” Chep Morrison sat mum in the mayor’s office as his national ambitions sank. Parents at two public schools Uptown had voted to accept black students; the Orleans Parish School Board threw “the entire burden of accepting a hugely unpopular social change on badly educated members of the white working class,” writes historian Adam Fairclough.

Allan Jaffe’s strategy to draw crowds at Preservation Hall was to build on word-of-mouth, and good press. The nightly performances became a center of gravity for Jim Robinson, Percy and Willie Humphrey, Papa John Joseph, Narvan Kimball, Billie and DeDe Pierce, Sweet Emma Barrett, and George Lewis, among others who enjoyed resurgent careers.

In late 1961, a David Brinkley NBC News report showed Jaffe playing tuba with the band and a parade of blacks and whites together. Perez’s White Citizens Council pressured the city to deny Jaffe a parading permit. Jaffe felt a deep moral revulsion at segregation. A capitalist to his marrow with his Ivy League business school degree, he knew segregation was bad for business at Preservation Hall.

Borenstein leased Preservation Hall to the Jaffes, their friendship secure. Eventually, he sold the property to them. As Freedom Riders rode buses through the South and endured beatings in the cause of civil rights, Jaffe rode his motor scooter to find musicians for gigs and help others with medical needs, as the club scratched along. The crowds kept coming. He helped musicians with small loans, building an esprit de corps while the city faced blowback from the very culture it needed to market New Orleans as a uniquely American place. How many jazzmen could they put in jail to resist the laws to which Leander Perez bowed?

In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act and Preservation Hall featured its first officially integrated band. Al Belletto, as the Playboy Club entertainment manager, was hiring Ellis Marsalis and other black musicians to perform in bands with white musicians. Mixed bands for white tourists were not like street demonstrations for civil rights. The new mayor, Victor Hugo Schiro, abhorred confrontations. The culture forced compromises on the city. A similar breakthrough happened with gays, albeit more slowly. The Krewe of Petronious invited guests in formal attire to a lavish tableau in a rented auditorium, as mainstream Carnival krewes had done for years, thwarting NOPD’s itch to bust-and-arrest. Complaints of police violence by gays and African Americans continued for decades; but as the drag queen beauty pageant became a fixture of Mardi Gras on Bourbon Street and gay Carnival krewes held by-invitation balls, the police attacks on closeted men dropped sharply by the ’80s. So, too, did the bar bribes.

Bill Russell was a nightly fixture at the Hall; he sold records, swept up, anything to keep the flame aglow. He had no telephone; people left messages for him at Preservation Hall. The place attracted attorney Lolis Elie, writer Tom Dent, and other blacks who became friends with the Borensteins, Jaffes, Clevengers, and other whites.

The photographer Diane Arbus spent time among the musicians and jazz followers in the Quarter in those years. Lee Friedlander visited often to photograph musicians. He became friends with Borenstein and Russell. “New Orleans was a magical place,” Friedlander told me in 1998. “Bill Russell had this incredible instinct for where bands were playing, and he had a very big stride. We’d get on a bus and go into an area, and Russell would say, ‘I think it’s that way.’ And we’d end up at a funeral or a march. Bands were used for almost any occasion. I thought I’d found a little piece of heaven.”

Friedlander photographed Sister Gertrude and became an early collector of her work. He found her presence deeply moving. “God told her in a dream that she should give up her guitar and illustrate the Bible,” he reflected. “She just did what God told her. He didn’t tell her to stop singing.”

She was a good client for a Bible salesman named Marcus Pergament; using some of the money she generated from her paintings, she bought Bibles and gave them away to all kinds of people. If there was a passage in the Bible she did not understand, she called Pergament for advice. He sold her the books; he should know the answer.

Sister Gertrude navigated the ’60s with an explosion of paintings obsessed by the battle between good and evil and the phenomenal beauty of heaven, the New Jerusalem. She underscored these themes with penciled lines of scripture, so that some of the pieces resembled scrolls, depicting herself in church, as a celebrant, pilgrim, witness, or just as spouse to the Almighty.

This the great master

and his darling wife.

they are using this wife

for this great Kingdom to

Brighten up their life.

They wanted some Body to work

through and its time for

them to Be well honored

and humored and well glorified too

I want to tell you darling

dada the world

is mad and it

seem like

they are mad with

I and you. But I’m gone

stand straight up not part the

way cause I no you are

able to carry me through.

In the poem, “they” are her two husbands, two parts of the Trinity who have commissioned her to preach. In that sense, God the Father and God the Son are using “this wife” to serve their purposes (“their lives”) and proselytize their people, the orphans in Gentilly now grown, black folk in the Lower Nine, the hookers, artists, tourists, and sinners along Bourbon and Royal, where she had been stationed with a guitar and jangling tambourine before the sales of her work brokered by Borenstein. Her two husbands and she, the darling wife, had a job to brighten the lives of people who needed inspiration to believe in everlasting happiness—her stated mission.

For her, the Lord was Master of creation; the poem speaks to God the Father, “dada.” She did a painting of Jesus with mustache in a tuxedo as groom: a comic flair she did not lack. “I want to tell you darling / dada the world / is mad” is a metaphorical nod to the crazed zeitgeist and roiling anger of the ’60s. She had felt the pinch of condescending looks from some white tourists in her street preaching; she had sat in the back of buses, she knew why African Americans were protesting. Contrasting that to the floor show of Bourbon and other Quarter streets, she wrote, in a short piece called “armageddon,” “never was national and Racial feeling stronger upon earth than it is now.” The leitmotif of hope in many of her images of the ’60s and ’70s is interracial harmony, biracial choirs, angel flocks of white and black. Various of her works are marked by the refrain, “The gift of God is eternal life.”

Musicians in Preservation Hall carried the melodies of church song from parades of the early 1900s—“The Saints,” “Streets of the City,” “By and By,” among others; the culture of arrival and becoming from the dawn of jazz was reaching a new threshold. As New Orleans Style drew tourists, the official city needed the culture to cleanse its racist image.

After years of playing guitar and tambourine, Gertrude Morgan was not about to watch a new freedom train pass by. On August 19, 1961, a Sunday morning, Borenstein sat in his art gallery next door to the hall with a recording engineer, the ethereal clarinetist George Lewis, the trumpeter “Kid” Thomas Valentine—and Sister Gertrude, determined to record; the song “Let’s Make a Record” in her gravelly alto is marred by inexperience—she was not a jazz vocalist; for all of Lewis and Valentine’s effort to embroider a melody, you can almost feel them wincing. The disastrous recording is a time capsule showing how far she had to go if her music would ever work on wax.

Jaffe the hefty tuba player joined the Preservation Hall Jazz Band for tours he organized, and recordings, putting the business in the black. As one band traveled, another played the Hall, with vinyl records for sale at the breaks. Borenstein, meanwhile, arranged for Sister Gertrude to give a Sunday morning service, when the Hall was closed, for invited friends—Bill Russell, Dick Allen, the LSU folklorist Harry Oster, who drove down from Baton Rouge, Dianne Carney of Ballet Hysell, among others, thirty or forty guests each time.

“Some things are hard to put into words, they’re so beautiful and spiritual,” reflects Sandy Jaffe, across the bridge of time. “Sister Gertrude always wore a white bonnet and white dress; she was very sure of herself. Sometimes she did a beautiful drawing for the sermon but wouldn’t leave it for Larry. I think he understood her and she him, very well. When they spoke it evolved into a deep conversation that came around to him wanting that piece to sell. They had a discussion like two CEOs at Davos about his not having an extra painting, could she please paint another small one? She wouldn’t unless she was motivated.”

“My mom used to talk about Sister Gertrude as wanting to spread the gospel,” recalls Sacha Borenstein Clay, born in 1963, the middle child of Larry and Pat’s three. Pat’s father was Jewish, her mother Baptist. “My mom believed that Sister Gertrude was the real deal, a prophet.”

When Hurricane Betsy inundated the Lower Nine in 1965, Sister Gertrude was living in a home at 5444 North Dorgenois Street, which sustained heavy damage. Borenstein and Jaffe bought the house, oversaw repairs, and provided Sister Gertrude a home, rent-free. She called it the Everlasting Gospel Mission and began holding services in the front room. Old enough to be their mother, Sister Gertrude had effectively been adopted by two middle-aged Jewish boys who saw to her needs; their family members and friends formed a loose support network as the house became her space for living, painting, and worship. She could be abrupt in ending the services, telling guests, like a guardian housewife, “Time to go. Jesus needs his pills.”

Borenstein arranged for her to sell works at the first New Orleans Jazz Festival and Louisiana Heritage Fair, in 1970. The program cover reproduced two of her self-portraits. That same year, he shepherded her work into three major exhibitions: Twentieth-Century Folk Art, at the American Folk Art Museum in New York; and the nationally traveling exhibitions Dimensions of Black, by the La Jolla Museum of Art, and Symbols and Images: Contemporary Primitive Artists, by the American Federation of Arts. In the early ’70s, Sister Gertrude also had a booth at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, which further increased her sales and visibility. At a New Orleans Museum of Art exhibition in 1973, she sang and played guitar for the opening, which included three other folk artists.

As she did paintings of various sizes, decorated hand fans and other objects, she pressed Borenstein for another shot at recording—she wanted musical permanence, too. Since her disastrous 1961 recording attempt, Borenstein had reason to resist; however, he had seen the confidence as her tambourine rhythms melded with the singing and preaching at Jazz Fest exhibitions. She agreed to record alone; the engineer set up at Borenstein’s gallery, which by 1971 was on Royal Street. By this time she was signing some of her work as “Prophetess Morgan, the lambs wife the lord of host wife to,” suggesting that she felt herself a seer, an evangelist prescient on things to come.

Let’s Make a Record has 14 cuts. Her rough voice rolls in warm undulations of scripture-citing to the fluttering tambourine, until she lessens the tempo of the hand percussion into a slow current, like a background chorus, to her preaching. The third cut, “I Got the New World in My View,” draws from Book of Revelation, in visions not of apocalyptical battle but of the singer as pilgrim entreating her listeners to join the road to New Jerusalem. With the tambourine thrumming, her voice drives a charging up tempo, with a lasso-like melody.

I got a new world in my view

And my journey I pursue . . .

Yes I’m running

running for the city,

I got the new world

in my view.

In another song, she situates the Revelation author, John, on the island of Patmos and throws off an aside, “let not your heart be troubled, dear ones.” She sings of “a New Jerusalem coming down, certainly a person is a city.” But the most remarkable of the 14 songs is “Power.” Sister Gertrude sings “power… power,” in a chant to the throttling tambourine, reaching a state of near-ecstasy, crying,

Yes send power!

Power, Lord, power!

I want my power!

I want my power!

The drive of the hypnotic repetitions carry her into a fugue state as she beseeches heavenly power for light over darkness. “Power” stands alone in the vast canon of New Orleans gospel music; not even Elder Utah Smith with his seraphim wings and electric guitar touches the raw intensity of Sister Gertrude’s spiritual witness.

Allan and Sandy Jaffe lived near Preservation Hall in a two-story Creole cottage, raising two sons. Russ earned a law degree before becoming a specialist in speech pathology. Ben, an Oberlin graduate, plays tuba, double bass, and has been director of Preservation Hall and leader of the band for nearly two decades. When the boys were growing up, the double parlor had tubas, saxophones, valve oil, spit stains on the floor (tuba players work up lots of saliva), a piano covered with mouthpieces and a wall lined with Noel Rockmore paintings of New Orleans jazz. Born in 1971, Ben Jaffe as a kid was surrounded by musicians, from an antique Willie Humphrey on clarinet to the much younger clarinetist Michael White; he watched the men on break in the patio behind the Hall—phone calls, joshing, music talk, business talk—rituals in a way of life.

“Sister Gertrude was one of those spirit figures in our life like Sweet Emma Barrett, who played piano and sang in the Hall,” says Ben Jaffe. “Sister Gertrude’s art work hung on our walls. We would go to her house, sometimes for Sunday school. That’s how we were raised, so it felt normal. There are certain spiritual people beyond any one doctrine. She painted the New Jerusalem. I knew about Jerusalem from synagogue. The music she played and sang sounded like kid songs to me—just stories. Making the pilgrimage to her house down in the Ninth Ward was something my dad would do with his brotherhood of friends, Larry Borenstein, Alan Lomax, and Lee Friedlander, this small group who understood New Orleans. First we’d go to the A&P on Royal and St. Peter and stock up on groceries for her. She had this amazing yard, filled with four-leaf clovers, and as kids we would pick clovers. She would sing and preach, pull out a book and do a little prayer ceremony. She used her paintings for the kids, teach scripture from the painting itself.”

Borenstein was brilliant at getting her work to the public, educating collectors on outsider art, folk art, primitive art, the designation for artists poor, uneducated, and talented. In 1974 Sister Gertrude stunned him by saying that she was finished painting. Borenstein was perplexed: her health was good. With mounting interest from museums and collectors, she was in her prime. Why stop? Because the Lord had told her, she reported. One can picture her stoical smile at the perplexity of her agent, friend, and caretaker. All those years selling her work, opening her doors, building her reputation—and she just quits?

But the arc of her life makes perfect sense: what draws from heaven must resolve itself to earth. When God says quit, you quit.

Borenstein put together a collection of her best works, contacted a wealthy collector in Chicago, and negotiated a major sale. His interest in selling her work then dwindled. The Jaffes held a major collection for many years. Sister Gertrude made one exception in 1979 for a painting at the request of a friend, but otherwise maintained her fast. She died, at 80, on July 8, 1980. Borenstein died a year later of heart failure at 62. For all of his frustration over her decision to stop, Larry Borenstein would have been deeply pleased at the reception of her work in the 1982 landmark exhibition at the Corcoran Museum of Art in Washington, D.C.—Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980, an all-consuming project by his friend, and hers, Bill Fagaly, the New Orleans Museum of Art curator. After many years of research, Fagaly organized the 2004 retrospective Tools of Her Ministry. In the years since her works have escalated in value.

The painted world that Sister Gertrude inhabited was purely of her own making, the mystic’s dedication to God, making art to glorify Him, discovering herself in the process. The autobiographical poems and writings were like her music and sermons, acts of worship to the Lord.

The mingling of art and music that gave birth to Preservation Hall echoed a layer of her personality. The hymns that “the mens” played as dirges in the funeral processions are sacred statements, the opposite face on the cultural coin of hot, sexy lyrics of blues and dance tunes. She was there, a presence if not a player, as the rebirth of the ’60s saw the walls of segregation fall as music sounded from the dawn of jazz.

There is something beautiful about her holy life in that bohemian carnival. Saints are stubborn, notoriously single-minded people. They raise hard questions and refuse easy answers. By the gauge of organized religion we know perhaps too little to call Sister Gertrude a saint. But the woman who harbored homeless children for nearly two decades after her arrival from Alabama, the missionary who sang for inmates at Parish Prison in the 140s, and in her last two decades painted a river of images celebrating Jesus as her Airplane was a rare personification of virtue pure, virtue simple, a saintly figure just the same.

From City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300. Copyright © 2018 by Jason Berry. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.org