The Sapphires could be Australia’s version of Dreamgirls, a sentimental coming-of-age flick about a group of young black girls on the rise to fame singing Motown hits in the ’60s, but it’s not—it’s that and much more. After all, the charming period piece received a 10-minute standing ovation at its debut screening at Cannes last year. Out in select theaters today, the story is set against the backdrop of a rural village in Australia and the war fields in Vietnam, touching upon deep-rooted Australian racial divides and the politics of war.

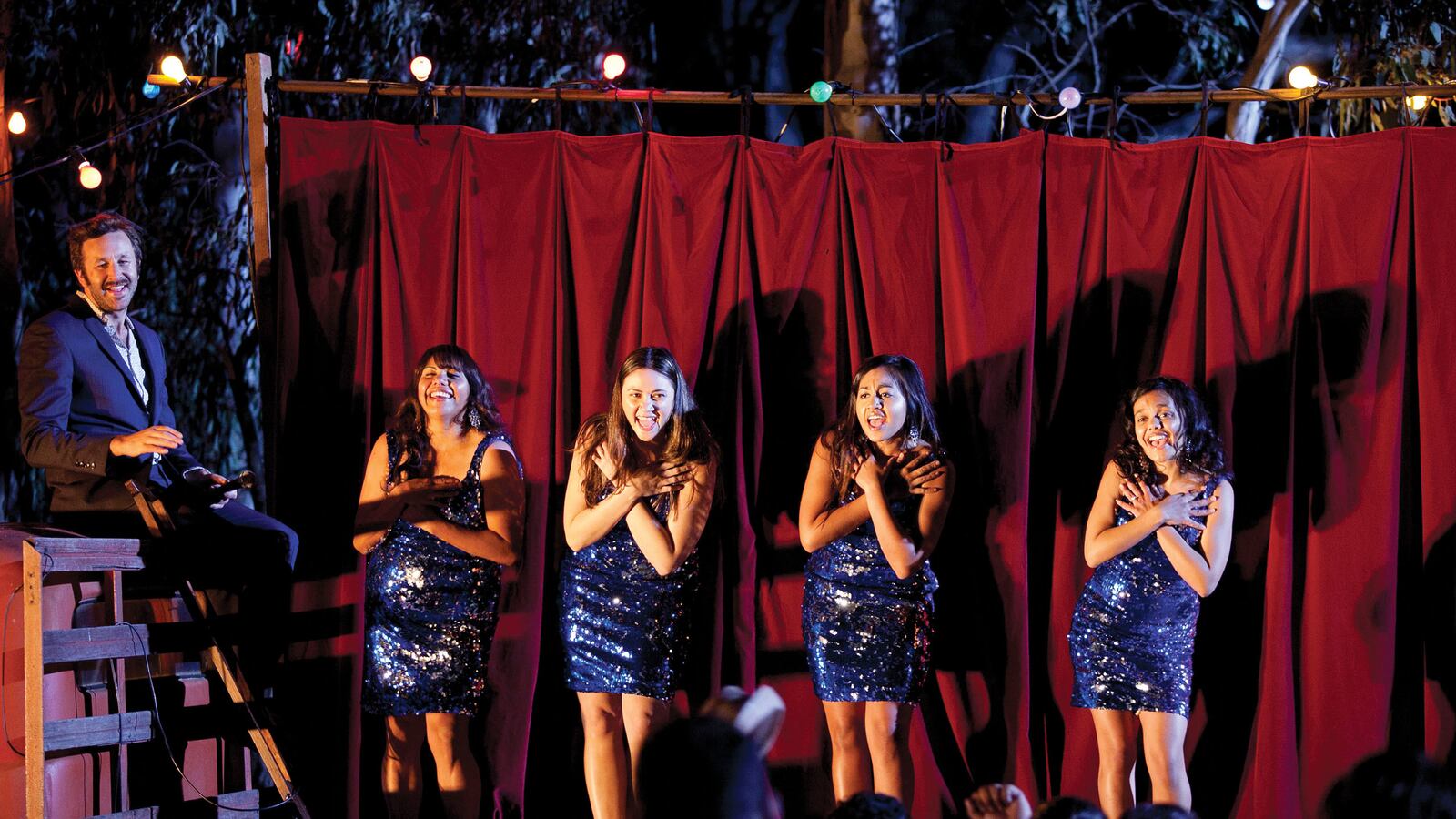

Although this spirited film tackles sensitive issues, The Sapphires somehow manages to stay lighthearted and inspirational throughout—and does so effectively. In the movie, three Aboriginal sisters and their cousin win a competition for a paid gig in Vietnam to perform for American troops during the war. Their charismatic and adorably bumbling-drunk music manager, Dave Loveless—portrayed by the rising Irish comedian Chris O’Dowd (This Is 40, Bridesmaids)—steers the girls from crooning country-Westerns to soulful classics and channeling the Supremes for their inner diva goddesses. The girls, in sparkling ’60s-era dresses, shimmy on an adventure surrounded by budding romances, war crossfire, and racial prejudice.

The story of The Sapphires was inspired by real-life events surrounding co-screenwriter Tony Briggs’ mother, Laurel Robinson—whom he tenderly calls “mum”—and his aunt Lois Peeler, who were two of the original Sapphires members to perform in Vietnam. The other two R&B crooners in the group, sisters Beverly Briggs and Naomi Mayers, protested the war and stayed back in Australia.

“I wouldn’t tell you the language she said,” Robinson tells The Daily Beast, laughing about Beverly Briggs’s reaction to her going to Vietnam. “It was very powerful and made me feel quite stupid. She is quite a formidable woman who was a trailblazer in politics.”

However, that didn’t stop Robinson from leaving for Southeast Asia, and she didn’t realize at the time how much of a maverick she was when she asked her mother to sign legal documents granting her permission to leave the country—a requirement since she was younger than 21. Only a year earlier the Australian government had approved the amendments of the 1967 Referendum, which removed discriminatory sections against the indigenous group.

“At that time, Aboriginal people were only just granted citizenship,” Briggs tells the Daily Beast. “We were only just counted as human beings, literally. We were classified as flora and fauna.”

“Being able to sign papers to allow her daughter, who is Aboriginal, to travel anywhere outside of Australia was very new and fresh,” he continues. “Mum didn’t have any idea it was quite a momentous occurrence.”

Robinson was so affected by the rampant racism in Australia that she even quit school at age 15 because she was discriminated against by two nuns in a Catholic secondary school she attended. She was sent to Melbourne to live with her cousin, a member of the Sapphires, thus setting in motion the events that took place. Despite the societal changes, she still sees racism in primary schools today.

Briggs was dealing with another dark chapter in Australian history when he decided to write about his mother’s experiences, fresh from acting in a play about the Stolen Generations—a controversial government policy that went in effect until the late 1960s that removed Aboriginal children from their homes and forced them to live with white families or in institutions. He touches on this subject in The Sapphires with one of the characters, Kay (Shari Sebbens), who was one of the “stolen children” and finds difficulty reconciling with her Aboriginal family after her cultural assimilation. “The subject matter was difficult, but worthwhile,” says Briggs about the play. “When I went off of that, I wanted to do something more lighthearted.”

He began asking his mother about her experiences in Vietnam, and thus began the idea for his story, which he made into a play before adapting it for a feature film. When asked about the differences between the film and real life, Briggs mentioned that each character is not based on anyone in particular, but an amalgamation of his favorite people in his life. The main character, Gail, is made up of three people: his mother, his late aunt who pushed him to become a writer, and Mayers, the chief executive officer of the Aboriginal Medical Service. The character of Dave, meanwhile, was wholly created for the stage and film.

“A lot of what you see on screen comes from my personal memories,” Briggs says. “They’re snippets in a way of what I remember as a young boy growing up. Really good memories like the story of my mother and the memories especially with music.”

In the film, the trip to Vietnam helps the girls learn about themselves and each other, and they get a breather from the prejudice in their own country by performing for enthusiastic U.S. troops eager to ease their minds from the harsh realities of war with fleeting moments of entertainment. A seminal moment in The Sapphires is when Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated and the girls sing a moving song of peace and acceptance to the troops to uplift their spirits. Their small world—previously limited to the Shepparton-Cummeragunja area—expands as they meet African-American GIs in Vietnam. One Sapphire, Kay, falls for a black soldier, even as she struggles with her Aboriginal identity. Together they all face the dangers of war.

When Robinson thinks back to when she returned from her tour in Vietnam, she found that even though the majority of her family and community were proud of her, nothing had really changed on the surface. Prior to her trip, she hated politics, but when she returned, she was inspired to help her people and began working for the Aboriginal Medical Service in Sydney. The social climate at the time made it difficult for Aboriginals to receive medical and emergency care in hospitals, but the service aided in covering that health-care gap and has been doing so for the past 43 years—an accomplishment Robinson is proud of.

As for Briggs, he hopes that The Sapphires—the most successful Australian film of 2012—captures a world and experience largely unknown to the audience, one filled with beauty and song.

“I hope they get a sense of joy and understanding of who Aboriginal people are,” he says, “and walk away from it with a smile on their faces.”