New York defense attorney Theodore V. “Ted” Wells Jr.—the battle-hardened litigator helping scandal-tarred Governor David Paterson in his hour of need—is a strong, not-so-silent type who is not afraid to cry.

The waterworks tend to switch on at moments of teeth-grinding stress and sweet relief.

He’s not someone Cuomo will take lightly.

He wept in May 1987 when a Bronx jury cleared his client, Reagan-era Labor Secretary Ray Donovan, of fraud and larceny charges after a nine-month trial. He wept in February 2007 during his closing argument on behalf of I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, the top Dick Cheney aide charged with obstruction of justice and perjury, when he noted that Libby “has been in my protection for the past month,” and begged the federal jury in Washington, D.C., to find his client innocent and “give him back to me.” The jurors, ultimately unmoved, returned a conviction.

And though he kept his composure in December 1998, when a different Washington jury acquitted Clinton-era Agriculture Secretary Mike Espy of taking illegal gifts from companies he’d regulated, Wells lost it when he met with jurors immediately after the verdict.

“After I was acquitted on all 30 counts, the jurors asked the judge if they could see me. It was highly unusual, and I went back to the jury room with Ted and my other lawyer, Reid Weingarten,” Espy recalls. “They wanted to explain why it had taken them so much time to get to an acquittal. It took them half the day to deliberate, but they said most of the time was spent choosing a foreperson. And then they said, ‘A bunch of us are smokers, so we kept taking cigarette breaks. So that’s why it took us so long. We weren’t deliberating on whether you were guilty or not. We always knew you were not guilty.’ That’s when Ted started crying.”

The 59-year-old Wells—who, like Espy and Paterson, is African American—will mostly be dry-eyed and, if necessary, combat-ready as he tries to make sure that the governor serves out his term, avoids criminal exposure and otherwise defuses the investigation into whether Paterson and the state police interceded to quash a domestic-violence complaint filed against a top aide by a former live-in-girlfriend.

Wells—a partner in Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison and co-chair of the 600-lawyer firm’s litigation department—declined to comment for this story. Ditto Paterson—who was forced to abort his election campaign over the controversy. Cuomo, who wants Paterson’s job, belatedly recused himself from the probe on Thursday, after watching his approval rating slip drastically, especially among minority voters, since taking the case two weeks ago at Paterson’s request. Cuomo said he would appoint the state’s former chief judge, Judith Kaye, as an independent counsel to oversee the investigation of the issues surrounding the governor, including whether he lied to the state ethics commission about his use of Yankees World Series tickets.

It’s the kind of tricky, high-profile, politically sensitive case on which the Harvard-trained Wells (with an M.B.A. as well as a J.D.) has made his reputation. He appears to be the opposite of a publicity hound: over a long and newsworthy career, he had granted only a handful of press interviews. Among countless civil and criminal cases, for clients as diverse as Philip Morris and Michael Milken, he successfully defended former Queens Congressman Floyd Flake and his wife from embezzlement charges, protected former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer from an indictment in his prostitution scandal, and helped Former New Jersey Senator Robert Torricelli avoid prosecution on alleged campaign-finance violations. After Cuomo’s announcement, a couple of New York legal experts, who asked not to be identified, said Wells probably had played a role in the attorney general’s decision to hand off the Paterson investigation. The attorney general’s spokesman, John Milgrim, didn’t respond to my request for comment.

“Ted is a great choice for the governor,” says prominent defense attorney Gerald Shargel, a Daily Beast contributor. “He is a fabulous trial lawyer, he is very smart, and he knows how to read a jury. He has a common-man appeal and he doesn’t talk down to jurors. He also commands a lot of respect in the legal community. He’s not someone Cuomo will take lightly.”

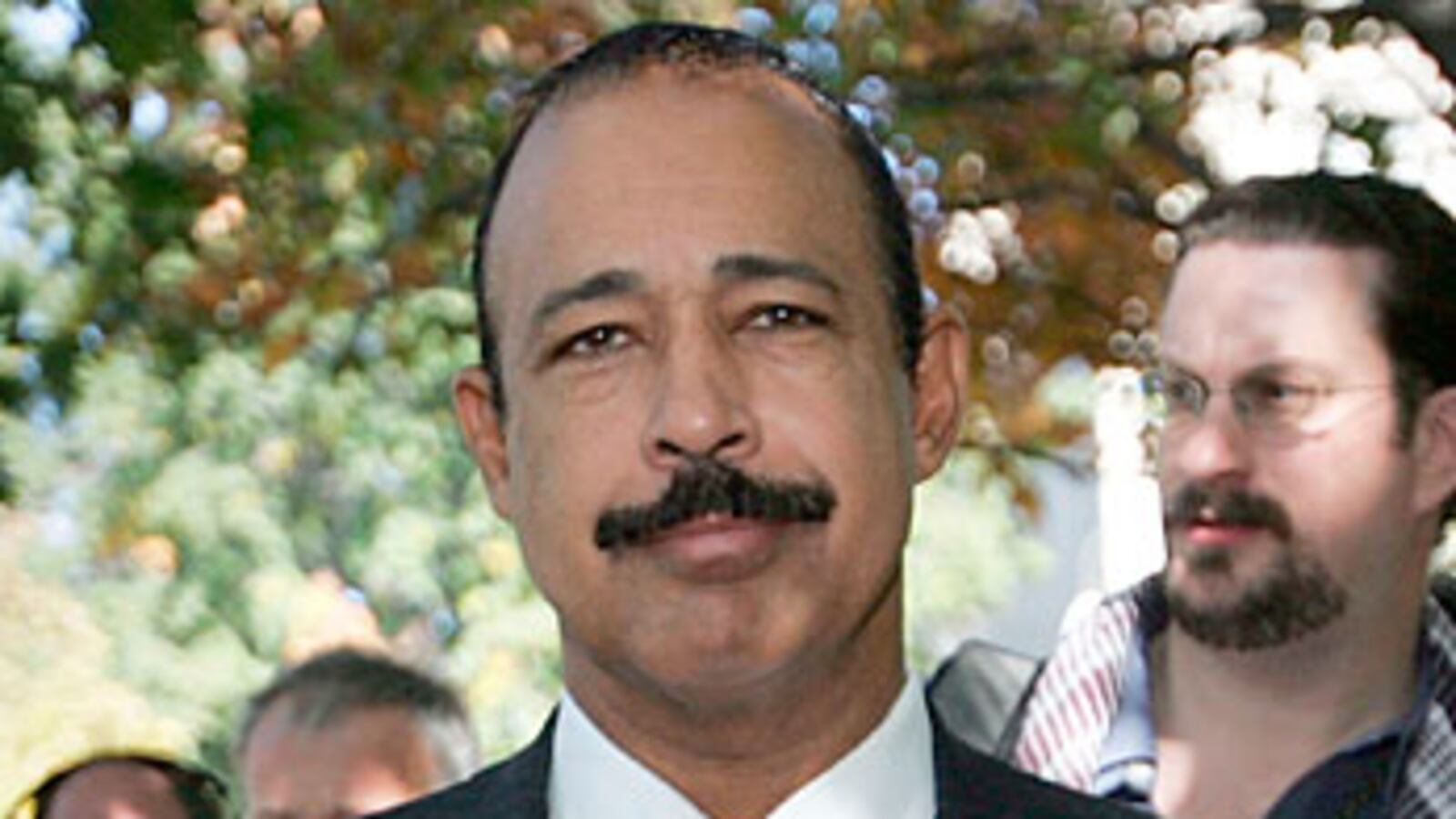

Manhattan Defense Attorney Marc Fernich calls Wells, a six-foot-three former high-school and college football player who sports a rakish mustache, a “compelling, charismatic figure and captivating speaker with a folksy demeanor that's like catnip to juries. He’s a powerhouse white-collar defense lawyer who is gifted at making the complex very simple.”

He is, not surprisingly, supremely well connected—equally at home in a boardroom and a courtroom. A staunch Democrat who lives in New Jersey, Wells is close to former New Jersey Senator and Governor (and Goldman Sachs Chief Executive) Jon Corzine. Wells’ wife, former Rutgers Law School assistant dean Nina Mitchell Wells, was Governor Corzine’s secretary of state, and Wells himself was national treasurer of former Senator Bill Bradley’s 2000 presidential campaign.

Wells is famous among fellow lawyers for mastering his material with obsessive preparation, often spending weeks on end, before a major trial, holed up in a hotel room strewn with briefing books and stacks of documents.

“Ted is a fun-loving guy, but he has a serious side—he’s a real workaholic,” says renowned defense attorney Gerald Lefcourt, who recalls meeting Wells a quarter century ago when Lefcourt was defending the American captain of a cargo ship found to contain 40 tons of marijuana, and Wells, assigned to the case as a public defender, was representing one of the Colombian crew members.

Wells steeped himself in the minutiae of Coast Guard procedures and jurisprudence on the high seas, and Lefcourt recalls him as a standout among all the attorneys on the trial. “I saw a guy who was not only excited about the litigation, he was also somebody who had great instincts and wanted to be involved in every aspect. A lot of lawyers were assigned to defend the Colombian crew members, but Ted was the only one who we really felt had a simpatico understanding of the whole case.”

Wells grew up in segregated Washington, D.C., the son of a mailroom clerk and a cab driver who divorced when he was a kid. He was raised by his mother. A star center on his high school football team, he attended college on a football scholarship at Holy Cross in Massachusetts, where one of his fellow students was Clarence Thomas. Unlike the future Supreme Court justice—whose life was rife with angry, radicalizing moments that pushed him from Black Panther supporter to Ronald Reagan Republican—the affable Wells remained a Democrat, animated by his own ambition and sense of justice.

Washington journalist Denis Collins, who was a juror in the 7½-week-long Libby trial, says Wells did an excellent job defending his client against federal prosecutor Patrick J. Fitzgerald, although it was not sufficient to win acquittal. “He had very little to work with,” Collins says. “And he really, really worked hard. He was like a combination of preacher and lawyer, depending on who he was looking at on the jury. You could really see him trying to work any angle he could. And he was very entertaining. If you think of it as a piece of music, Fitzgerald stayed pretty much on one key and Wells was hitting the high notes and the low notes. It was a pleasant experience to see a really great lawyer do his thing.”

None of Wells’ virtuosity saved Scooter Libby from prison—it took a presidential commutation from George W. Bush to do that. Likewise, as the investigation of David Paterson proceeds to its conclusion, Wells might be able to do little more than soften the blow.

“Ted has a very good street sense, and he’s politically aware, and he will provide the governor with the kind of advice he needs,” Lefcourt says. “If he thinks it’s appropriate to fight, he will tell the governor why. And if he thinks it’s appropriate for the governor to cut his losses, he will tell him that, too.”

With or without tears.

Lloyd Grove is editor at large for The Daily Beast. He is also a frequent contributor to New York magazine and was a contributing editor for Condé Nast Portfolio. He wrote a gossip column for the New York Daily News from 2003 to 2006. Prior to that, he wrote the Reliable Source column for the Washington Post, where he spent 23 years covering politics, the media, and other subjects.