For those of us who cannot get enough good longform in our life, A Man’s World, the terrific new anthology of Steve Oney’s magazine journalism, is a treat. Oney is a longtime freelancer—most celebrated for his devastating account of the lynching of Leo Frank—who has contributed to Playboy, GQ, Esquire, Los Angeles, and The New York Times Magazine. His work is unpretentious, sympathetic and attentive, as you’ll see in this engaging profile of Harrison Ford. Originally published as “An Ordinary Man” in the March 1988 issue of Premiere magazine (and featured in A Man’s World) it appears here with the author’s permission. —Alex Belth

By Steve Oney

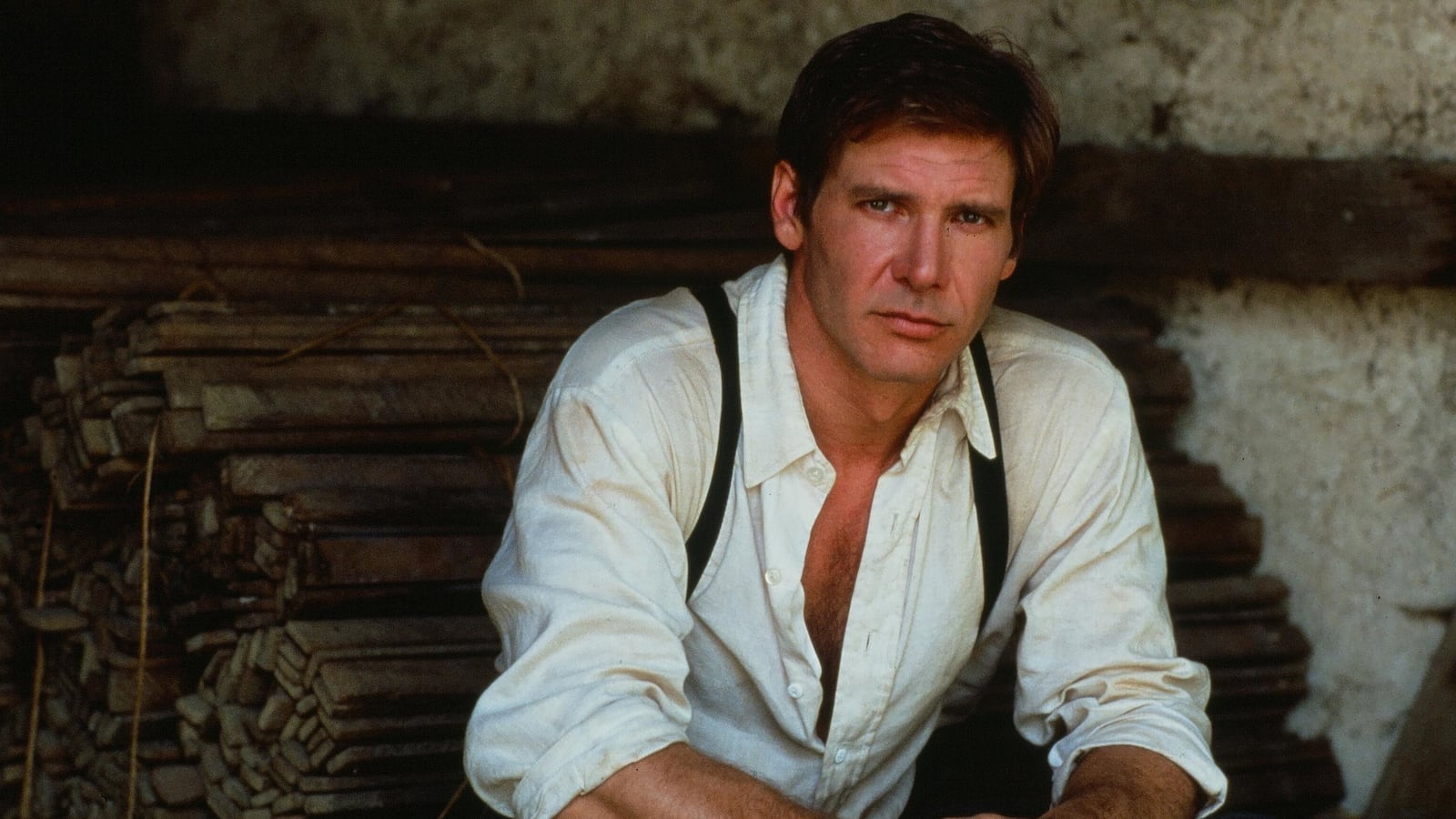

Harrison Ford is walking purposefully along a wooden plank sidewalk in a town somewhere in the Rockies. He moves with a sturdy grace, well-muscled shoulders shifting against the yoke of his denim shirt, hips working like ball bearings inside dirty Levi’s. Save for his sunglasses, which he wears as armor against chance recognition, he could be just another cowboy.

By Ford’s calculations, he only makes it into the big city—a one-stoplight affair on the edge of a National Park—about “0.3 times a week.” Although the place retains a smidgen of western integrity, it has largely gone the way of all mountain resorts. The streets are lined with white-water-rafting outfitters, real estate offices, and ski shops. The main square is anchored by a Ralph Lauren boutique. Ford feels fenced in here.

No wonder. On his 800-acre spread seven miles out in the country, elk and deer roam freely, bald eagles wheel overhead, and cutthroat trout shoot through the creeks. The ranch is dominated by a two-story house of Ford’s own design that a friend, relishing the obvious contradiction between the dwelling’s massive size and plain style, terms a “Shaker mansion.” Ford calls the compound a “refuge for animal animals and human animals.”

But even a man more at home on the range than in civilization has to take care of business from time to time. The sooner the actor gets his chores done, the sooner he can get back to the Ponderosa.

At a sporting-goods store, Ford buys a pair of size-twelve boots with leather uppers and rubber bottoms. “These are basically industrial-strength slippers that I can pull on to step out into the 8-degree cold while the dog is encouraged to do her business,” he says.

At a bicycle-repair stand that doubles as a wood-stove retailer, Ford picks up a couple of fireplace grates. “I don’t want nice—just something that works,” he says, setting two unadorned pieces on the counter. The proprietor, an unreconstructed hippie, is friendly with Ford, and as he rings up the purchase, he nods at a fellow who’s shadowing his famous customer. “Is this guy getting local color?”

“Yeah,” Ford answers and in parting adds, “Thanks, local.”

Back outside, Ford pauses to savor the joke. Laughter softens his rugged features—the imposing eyebrows, stern nose, and that trademark little scar just below the lip. For an instant, he seems like a playful golden retriever: boyish, open, mischievous.

But the moment quickly passes. One more task and Ford can retreat to the hills. He has a lunch date at the White Buffalo Club, a restaurant duded up in faux Victoriana that he says provides “a place for us to bring out-of-towners and show them we’re as capable of excess as they are.” In response to the suggestion that there must be a homier spot for a conversation—a location that speaks to his heart and reveals something about the life he has fashioned for himself in this high, pristine setting—Ford stops and faces the man trailing him. “I’m going to give you no options,” he says evenly, his eyes narrowing, his aspect suddenly hardening. “You cannot see the backstage part of my life. You cannot come to my ranch.”

With that, Ford’s mood again lightens. “My wife and I came up here because we wanted a private place with four seasons—three of them winter. But enough about me.”

***

Harrison Ford will be taken on his own terms or no terms at all. And what’s more, he won’t even go that far unless he has a good reason. On this late fall afternoon, that reason is his new movie, Roman Polanski’s Frantic, a project about which Ford is excited. “I’m more than happy to talk about it,” he says. The picture, which was shot in Paris last year, should complete the process that Witness and The Mosquito Coast started: the elevation of the actor’s place in the Hollywood pantheon from pulp genre hero to legitimate leading man.

Because of Ford’s winning performances as interplanetary knight-errant Han Solo in the Star Wars series and swashbuckling Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Arc and its sequel, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, he had become stereotyped as a comic-book figure. Yes, he had dangerous good looks. Yes, he had presence. Yes, he made more money than just about anyone in Hollywood. But when it came time to cast the role of a serious male protagonist, he was always far down the list. “The way it used to work,” says Thom Mount, producer of Frantic, “is that scripts would go to Jack Nicholson or Warren Beatty, and if they turned them down then they’d go to Harrison. But they’re all growing too old for such parts. Now Harrison gets them first.”

As a star vehicle, Frantic provides Ford with the kind of part that comes along very rarely indeed. In the role of Dr. Richard Walker, an American cardiologist whose wife is kidnapped by Middle Eastern terrorists after she mistakenly picks up the wrong suitcase at Paris’s Orly Airport, the actor is in nearly every scene. The movie’s success depends almost entirely upon him giving a convincing portrayal of a man willing to go to any lengths to save what is dearest to him.

But as far as Ford’s career goes, the most rewarding thing about Frantic may well be the opportunity the film gave him to work with Polanski. “I think Roman is one of the best directors I’ve ever worked with,” Ford says. Adds Mount: “The difference between Ford as Indiana Jones and the Ford of Frantic is that Polanski, unlike Steven Spielberg [director of both Indiana Jones pictures], recognized Harrison’s complexities and brought them to life. He saw that Ford is much more than a cartoon character.”

***

Ensconced in a secluded booth at the White Buffalo, Harrison Ford is making short work of a pasta entrée. Now that he has set the ground rules—not only is the ranch off-limits but the town is to remain unnamed and the state to go unmentioned—he seems less edgy. He’s willing to come along real peaceable-like as long as one agrees to look down the barrel of his preconditions.

“This is just too small a pond,” he says, hoping to explain his wariness. “I have people show up in my driveway with Wisconsin plates and long lenses on their cameras, and I don’t like it. They might not even be freaks, but they’re just not operating on the same wavelength I am.”

Ford feels that such intruders “deny me a real life, and I don’t want to be denied a real life.” His sense is that he can hold the wolves at bay by keeping a low public profile. Anyway, he says, the kind of celebrity bestowed upon actors by the press is distasteful at best and always transitory. Take, for instance, People magazine, which Ford has disdainfully renamed Peephole. “It just absorbs, digests, and shits out personalities like yesterday’s prunes.”

But on an even deeper level, Ford believes that by the nature of his job, he’s already revealed everything that anyone should reasonably want to know about him. “I just can’t imagine how much more you can expose yourself than what I’ve done onscreen,” he says. “You can’t know a person better. Who the hell do you think that is up there? Some total stranger? That’s me.”

By this logic, Ford’s work in Frantic can be taken as that of a veritable exhibitionist. For starters, both the way he got the part and the motivation that drives his character attest to one of his central obsessions: a fear of being unable to protect the people he loves.

“A year ago, near Christmas, my wife [screenwriter Melissa Mathison, author of E.T.] was working on a script for Roman about Tin-Tin, the Belgian children’s book hero,” he says. “She had to go see him in Paris, and it was at the height of that terrorism business. She was pregnant, and I didn’t want her to go alone. So I tagged along. That was the first time I met Roman.”

During his stay in France, Ford sat down with Polanski at the director’s apartment, “and he told me the story of Frantic in two hours. It was terrific—a compelling story about a man who loved his wife.” Because of the actor’s worries about his own wife, the tale hit especially close to home. “I was very receptive, because I’m always worried about her. That pretty much defines my reality.”

While watching Polanski act out the movie, Ford realized that the horrors he could only contemplate were, for the director, hideously real. Because Polanski had endured the murder of his wife, actress Sharon Tate, by Charles Manson and his disciples, he “lent elements to it that I could never begin to imagine. It was clear that this was deeply emotional for Roman. To think how I’d feel if the circumstances had happened to me was. Well … When it was over, I said, ‘If that’s what it’s going to be like when it’s written down, I’ll do it.’”

Frantic also reveals other aspects of Ford’s personality. “Harrison is simultaneously very loose and very tight,” says a longtime friend. “Polanski saw that and used it.”

In a casual encounter with Ford, these contrasting traits crop up immediately. Over lunch, as he watches the waiter expertly uncork a bottle of wine, pour without spilling a drop then drape a towel with a matador’s precision, he blurts out, “This guy is no actor.” Almost simultaneously, however, as he tries to describe a heart surgeon he met while preparing for the new film, he haltingly belabors the point. “Aspects of his personality … were … expressed by the way he used his hands … a certain authoritarian aspect … Uhh … authoritative is perhaps a better word? In fact, it is a better word. This was a particular kind of guy.”

It wasn’t until after he got to know Ford that Polanski suggested that the character of Richard Walker should be a cardiologist—a profession that demands meticulousness. The director’s goal was to capitalize on his star’s conflicting impulses. Set him up as a figure accustomed to operating in an environment of scrupulous detail then plunge him into a netherworld where he will not survive unless he trusts his instincts. “In just a few moments at the start of the movie,” Ford says, “we have to show that this guy is used to wielding authority.” The actor hopes he accomplished the task by focusing on those aforementioned hands (“Surgeons have an incredible vanity about their hands”) to create an impression of assuredness. But as Walker grows more and more frenzied about his wife’s abduction, that sense of resolve vanishes, and Ford relied on “shadings of anxiety and degrees of frustration” to show a man who must fall back on his wits.

Ford believes the task of capturing his character’s metamorphosis was made easier by the latitude Polanski gave him to improvise with the script, which the director co-wrote with long-time collaborator Gerard Brach (Tess, The Name of the Rose). “Roman is actually pretty free in the shooting process,” the actor says. “If he can see it working before him, he doesn’t care as much as other writing directors whether he gets a word-by-word interpretation.”

Up to a point, Polanski approved of Ford’s tendency to tinker with his dialogue. “Often when Harrison read a line, it was a different reading than I anticipated, but it worked,” the director says. “Somehow it was more original, but it’s a bit dangerous. Later on during the rushes I said, ‘Oh, golly, I should have shot it the way I originally conceived it.’”

Since Ford invites speculation about the self-revelatory nature of his acting, another clue to his personality that Frantic provides can be found in his dedication to the movie as a whole and “not the character I play.” Ford’s style is Hemingway-esque. His mantra: proportion, discipline, appropriateness. His aim in a scene: “To make sure that we’ve got every drop that we can, that we’ve realized the thematic elements to the greatest, that we’ve made everything clear as a bell.” He believes he will have succeeded in the film if viewers remember Richard Walker’s problem and forget that Harrison Ford even exists.

Over coffee, while Ford is willing to continue talking earnestly about Frantic, he is, upon reconsideration, less eager to go any deeper into what the picture reveals about him. If he’s not going to give a tour of his back forty, he’s surely not going to open up the inner landscape. Everyone’s welcome to draw his own conclusions, but, Ford says, the iciness back, “I don’t have to explain how the damn thing works.” Then, shrugging like a lowly employee asked to justify management policy, he adds, “I just work here.”

A little embarrassed by how he knows he must sound, Ford relaxes his hostile expression, and something almost like pleading enters his voice. “I’d just rather be on down the road, back at work, attending to the myriad details that need to be attended to. Right now I’ve got to call a contractor about some storm-window adjustments. I want to look at a color going down on the floors at the house. I want to check with my wife about a rash on the baby’s back. I’m gonna call my kid and tell him that a plane ticket for his great-aunt’s funeral is coming. That’s all important shit.”

Holding his hands up as if to say “enough” Ford rises from the table and heads for the door. “I’ve got work at the secret place,” he says, his tone acknowledging the ludicrousness of it all. But come quitting time—“beer 30,” he calls it—he promises another audience.

***

Those who have actually been given leave to pass a day with Harrison Ford on his own ground describe it as a place that makes the actor “blissful.” It is so isolated that Ford had to cut a new road, bring in electricity, and bury septic tanks just to begin construction on the buildings—aside from the house, there is an office, a workshop, a hay barn, and a tack shed. It is so untamed that 65 species of mammals live there. In hopes that the property will remain undeveloped into perpetuity, the actor has granted an easement on it to a nature conservancy. “I really have more of a sense of stewardship about it than ownership,” he says. “I really want to preserve it for my kids—to let them know that this is what’s dear to me rather than a big pile of money in the middle of the floor.”

On a good day—“a day without reporters,” he deadpans—Ford is up early, mending fences, checking on damage caused by beavers, and making lists of things to do, occasionally inking them right onto the palms of his hands. He also tries to spend as much time as possible in reverie. “I look at a creek with fish in it, and it just sets off a chain of thoughts. The fish are there because the water’s clean. The water’s clean because somebody took care to see that irrigation ditches don’t flow into the creek. Or maybe the fish are there because somebody cleaned out a deep hole under a tree for them to live in.”

Ford’s love of the life he is building in the hinterlands leads him to believe he’ll never leave—and certainly not for Los Angeles, which he calls “one of the most hostile environments known to mankind.” With a new baby (ten-month-old Malcolm), a good marriage, “a business that lets me live anywhere I want,” and a few close friends (singer Jimmy Buffett appeals to “the shit-kicker in me,” the actor says, while L.A. gallery owner Earl McGrath satisfies a longing for intellectual debate), Ford, at 45, seems genuinely happy. It wasn’t always so.

Ford flunked out of Wisconsin’s Ripon College three days before graduation. His academic decline was brought on by “a tenuous hold on the minimum grade-point average and cosmic inattention.” This following a “bumbly adolescence” in Chicago during which he was “never real popular or real athletic or real anything.” The son of a Catholic father and a Jewish mother, he was neither fish nor fowl.

The one thing Ford was good at was getting jobs. “I’m real polite. I know how to sit straight and keep my head up. People think I’m not going to steal from them. Getting jobs is like acting.” In Chicago, Ford talked himself into a position as a chef with a Great Lakes cruise outfit even though he’d never cooked a meal in his life. Arriving in Southern California in the mid-‘60s, he hit the ground running on the same course, working by turns as a yacht broker in Laguna Beach, a management trainee for Bullock’s department stores (“I must have said something that led them to believe retails sales would be my life”), and a pizza maker in Hollywood. When he decided to become a carpenter, he simply went to the public library and read every book on the subject.

Of all Ford’s early jobs, carpentry was the one that actually spoke to his creative instincts. Stylistically his work was traditional. Technically it subscribed to the maxim “Form follows function.” When it came to quality, he urged clients to spare no expense. “‘Spend the bucks. Spend the bucks,’ that’s all he ever said,” recalls one customer. The work led to his break in show business.

Ford had always been interested in acting. While living in Laguna Beach, he appeared in a few plays. In one he caught the eye of a talent scout from Columbia Pictures and was given a contract, but it led only to bit parts, mostly on television, as bank robbers or bellhops. At the age of 30—already married to his first wife, Mary, and father of sons Willard and Benjamin—he did not seem headed to the big screen. Then he scored some carpentry jobs in Hollywood. He built Sergio Mendes’s recording studio and Sally Kellerman’s sun porch. Most important, he built a bed for Fred Roos, a casting director.

“Harrison was not conventionally good-looking,” Roos recalls. “He was also tight-lipped, standoffish, and most people thought he had an attitude. He’s an incredibly cranky guy. But I thought he was going to be a star, and we got along famously.”

Roos started auditioning Ford for “anything he was remotely right for.” Finally, he prevailed upon George Lucas to cast the actor as Bob Falfa, the straw-hatted badass who shows up in the closing minutes of American Graffiti (1973) to engage in a classic bit of teenage ritual jousting: drag racing. Ford turned in a memorably sneering performance that attracted favorable attention.

Roos, who by this point had begun producing films, became Ford’s angel. He gave him a part, for instance, in The Conversation as Robert Duvall’s leaden-eyed hatchet man. But it was on a picture for which he served only as a consultant that Roos engineered Ford’s big break. “I pretty much badgered George Lucas into casting him in Star Wars. He wasn’t high on George’s list. He didn’t know him like I did.”

Ford was on his way, but his ascent would not be seamless. “After Star Wars a funny thing happened to Harrison,” says Roos. “As good as he was people in the industry thought the movie succeeded because of its special effects. He was dismissed. He went off to Europe and made a sequel to The Guns of Navarone, and people started saying, ‘Oh, he isn’t a star after all.’ Even his work as Indiana Jones didn’t help.”

Then came Witness, and suddenly everyone was talking about Ford. “People started saying, ‘He’s really good,’” Roos remembers. “But he was always that good. He was always good with women. He was always funny. There’s a gag in Raiders of the Lost Ark where Harrison, after defeating all these swordsmen in hand-to-hand combat, has to face this huge guy in a turban carrying a gigantic scimitar. Well, Harrison just pulls out a gun, shrugs, and shoots him. That was Harrison’s idea, and it’s the funniest thing in the film.”

In the tone of a proud father, Roos adds, “He’s really a star in the mold of Bogart—tough, cynical, capable of taking care of himself. And maybe there’s a little Clark Gable, about whom there was absolutely nothing sentimental. I hate to say I told you so, but …”

Success, however, did not soften Ford’s “don’t tread on me” demeanor. During the filming of Blade Runner, in which he starred as a replicant hunter, he nearly came to blows with director Ridley Scott. “It was a grueling movie, and Ridley demanded so many takes that it finally wore Harrison out,” says Bud Yorkin, the film’s producer. “I know he was ready to kill Ridley. One night on the set, he would have taken him on if he hadn’t been talked out of it.”

Distant, recalcitrant, on occasion surly, Ford is in the end a man who goes to greater lengths than most to control what he will or will not do. Not only this, he makes life difficult for those who actually care about him. “In any encounter he’s always the senior and you’re always the freshman,” says actress Carrie Fisher, who first got to know Ford when she played Princess Leia opposite him in Star Wars. “I think he always felt I was too loud and a little out of control, and he’s the kind of guy who’d kick me under the table or fix me with a withering look to let me know it.”

In spite of Ford’s tendency to scold her, he and Fisher have remained close. She finds his prickliness well worth enduring. For one thing, she says, “I respect Harrison, which is an odd thing for me to say about anyone. He’s well-read, thoughtful. When I was twenty, he told me I was one of the smartest girls he’d ever met—I can’t tell you how that thrilled me.” But more than admiring Ford, Fisher genuinely likes him. She believes that his stormy moods are little more than thunder squalls tracking across a basically mild climate. “Just don’t wear the wrong clothes around him,” she says, “because then he’ll get you. He’ll turn into your dad.”

***

The Million Dollar Cowboy Bar is a fantasy out of Nudie’s of Hollywood. The bar stools are fashioned from tooled leather saddles. The bar top is embedded with hundreds of silver dollars. The chandeliers are huge, light-bulb-studded wagon wheels. In glass cases located strategically around the cavernous, main room, gigantic stuffed bears and bobcats stare down on cowboys and cowgirls who dance the western swing as a country band twangs away on stage.

After taking a long pull on a Corona, Harrison Ford looks up from his table with a chagrined expression. “I don’t come here very often, man.” Although the place is authentic in a campy kind of way, it is, to Ford’s thinking, a little bit of Vegas plopped down in paradise.

“I don’t go out much,” he says. “By the time dinner is over and the dishes are done, it’s time to think about what to do the next day, try to read part of The New York Times, watch a little TV. Generally, I go to bed early because we get up early with the baby.”

Tranquility is what Ford seeks here at home, not bright lights. He sees enough of those at work. He’s already signed up to do his next film, Mike Nichols’s Working Girl, a dry comedy he won’t discuss other than to acknowledge that he’s cast in a Cary Grant-like role. Then, in late 1988, shooting will begin on yet another installment in the Indiana Jones series. He won’t talk about that, either—“No can do,” he snaps when asked what the picture is about—but without prompting he offers his prediction of what the reviewers will say: “’Now that Ford has done these very creative roles, why does he do another Raiders film?’” Clapping his powerful, work-begrimed hands in a gesture of delight, he provides the answer: “Well, I’ll tell you, it’s the same process whether it’s a so-called serious movie or a not-serious movie. The job of acting is the same. What I really enjoy is the kind of problem-solving aspect of getting stuff off the page and on its feet, and for that there’s no one better than Steven Spielberg. He’s got one of the most facile minds you’re ever going to meet in movie making. And besides, playing Indiana is fun. It’s every boy’s dream. Jesus.”

During Ford’s speech, a king of the wild frontier wearing a black, ten-gallon hat appears at the table. Identifying himself as “Davy Crockett—a distant cousin of the original,” he extends his hand to the actor. “We’re mighty proud of you, Harrison. Mighty proud to have you live here.”

A pained smile flashes across Ford’s face as he returns the handshake. “Thank you, Davy,” he says in the same tone he often used in the Star Wars films when encountering some odd, extraterrestrial life-form.

In hopes of avoiding a group of Davy’s friends, Ford quickly settles his tab and hustles out the door. Already, a chill is in the air. In front of his truck—a serious, winch-equipped Chevy Scottsdale pickup—he pauses for a second to give the little metropolis a last once-over. Then he opens the driver’s door, bends over, and produces his new dog, Betty, who’s been asleep on the floor. A chocolate Labrador puppy not much bigger than a football, she’s cute as can be. “Come on Betty, this is no place for you,” Ford says as he climbs behind the wheel. While warming up the engine, he rolls down the window and with a leveling gaze tells his inquisitor, “I know I haven’t satisfied you, but I’m leaving you the same way I found you.” With that, he drives away into the night’s all-encompassing solitude.