The road is quietly marked off the two-lane highway that cuts through Latvia’s Gauja National Park—an endless realm of sky-scraping pine. It loops like a shoelace past a cluster of forgotten storefronts and a crumbling brick factory once used to mint Estonian currency. At the top of a hill a gentle glade gives way to a large structure made of metal and glass, built in an unforgivingly drab Bauhaus mash-up that was briefly in vogue during the latter part of the Soviet era.

The Ligatne Rehabilitation Center is a seemingly prosperous—if not forlorn—place where patients with arthritic symptoms can convalesce in the quiet of the forest. Nurses in white pillbox hats gently push their patients around in wheelchairs. Others rest under the shade of a tree, cigarettes in hand.

Although palliative techniques are practiced in earnest today, the entire complex was constructed as a front for one of the most crucial and strategic hideouts during the height of the Cold War—a bunker for some of the most senior members of the Soviet Union and 250 of their comrades.

Known by its code name “Rest House,” the underground base was completed in 1982 with the finest Soviet technology of the time, and was meant to withstand both nuclear and chemical bombardment.

If an attack by American forces had indeed occurred before the fall of the Soviet Union, the man in change of the secret lair was intended to be Boris Pugo, one of the most prominent first secretaries of his time. In fact, Pugo was such an ardent communist that while the USSR was on the precipice of collapse, he was manning the stormy seas as Minister of Interior Affairs. Ever the stalwart, Pugo was pivotal in organizing the August coup of 1991 to seize power back from Mikhail Gorbachev, which ended in failure.

Although the Ligatne fallout shelter was never used under catastrophic circumstances, it was Pugo’s final stand until he fatally shot his wife and them himself upon realizing that his precious USSR was indeed no more. The bunker, so crucial during the final years of the Cold War in the Baltic, was only declassified in 2003.

Today, it has opened its doors to curious travelers willing to undertake the journey out to the far-flung countryside beyond Riga, Latvia’s capital. And while the fetid stench of forgotten time still permeates its walls, a visit here makes for a fascinating journey through a wildly different era and psyche.

Upon entering the medical complex, the entrance to the bunker itself remains as discrete as one might think, wrapped around the bottom of an unassuming stairwell otherwise used by staffers to reach ailing guests upstairs. After passing through an iron door with a round crank, a small blueprint marks the official entrance into the secret shelter. The map of the complex reveals over 2,000 square meters of habitable space arranged in 90 rooms along three thin corridors that—when rendered on a drawing—look somewhat like prison bars.

The hallways are painted in muted greens throughout, which, according to Soviet psychologists of the time, was meant to promote happiness and wellbeing. Needless to say, the cloudy pistachio tone does very little to alleviate the claustrophobia induced by the oppressive metallic walls and snaking pipes overhead.

While moving toward the far end of the bunker, the angry whirr of the generators flick on, grinding to a steady speed in order to pump crucial bursts of oxygen throughout. The space was meant to function autonomously and had its own air purification system, a tapped well for potable water, and an independent power supply that could sustain its residents for three full months. Much of the technology incorporated into the design borrowed from submarine design principles, especially sewage and waste disposal.

During a state of emergency, the only connection between the bunker and the outside world was a sophisticated network of technology in the communications chamber. Arranged like a CERN computer showroom, the operations areas looked like a pilot’s cockpit with countless switches and knobs.

The ops center was a veritable “Situation Room” that had the scope of the Soviet Union fleshed out on a series of floor-to-ceiling maps with blinking lights. Untouched since its discovery in 2003, the plans showcase a constellation of other hidden bases and vividly renders the worst-case-scenario details of Russia’s total hydroelectric collapse—which cities would be submerged underwater, which could still be used to guard the nation against America and its allies.

Stacks of literature by relevant theorists and politicos like Marx and Brezhnev inhabit the cells along the hallway to the canteen. The modest eating area has more than a dozen tables, each punctuated by a small porcelain vase with a plastic flower poking out. A subtle mockery of its hostile surrounds, the flowers are a palpable reminder that very little has changed since the bunker was unearthed—each petal retains little flecks of dust from when they were “planted” in the mid-’80s.

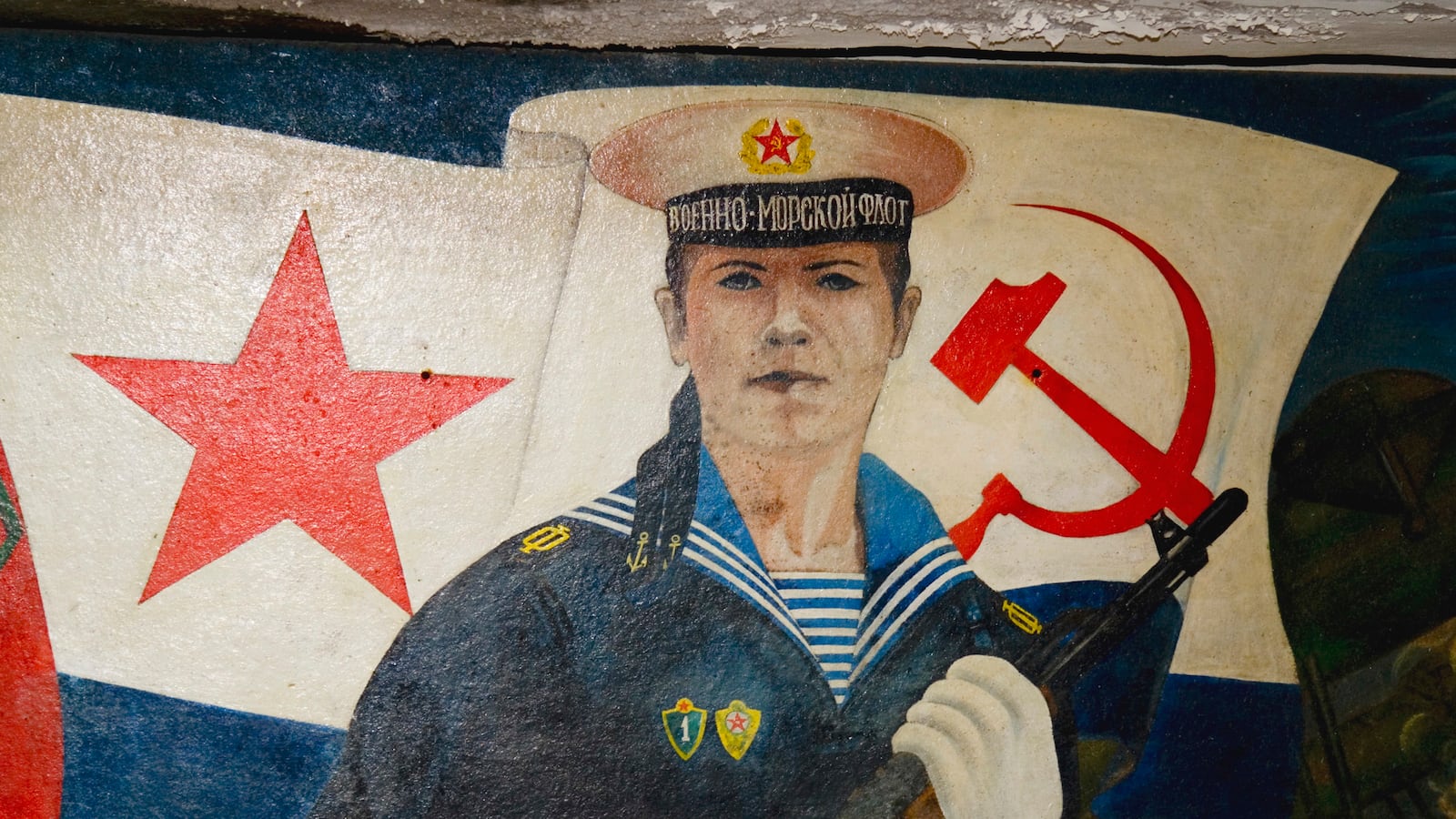

The canteen’s galley is very much in operation as it would have been during the Cold War. In fact, when visitors organize their tours well in advance, it’s possible to have a short meal—Soviet-style potatoes and pelmeni raviolis, of course—served with a shot of vodka, presumably procured from the stock of hospital anesthetizer used on the patients above. Pausing in the designated eating zone allows ample time to take in the “Vive Lenin” propaganda painted in brilliant red banners all along the walls.

The final room accessible to visitors is Pugo’s office, split into two distinct sections. His main bureau has the usual trappings of Soviet paraphernalia, including a framed portrait of Lenin and a “red phone” connecting the bunker to the Kremlin in Moscow. But what’s perhaps even more fascinating than Pugo’s Bond-villain-esque accouterments is the second suite just beyond.

A smaller space painted with a patterned variation of the signature coats of green, the room is rather spartan, possessing but one small bed, barely the size of one of those thin mattresses found in practically every college dorm room in America. It may seem simple and unassuming, but Pugo’s single bed speaks volumes about extreme Communist ideals: it’s the only bed in the entire complex.

No beds have been removed, no additional beds were ever meant to be added. Although the bunker was intended for 250 Soviet soldiers, it was only outfitted with a sleeping space for one—Pugo, the queen bee. The drones, as it were, had to rest at their stations, constantly maintaining the hive for the greater good.

The utter lack of beds provides a vivid commentary on the extreme nature of Communism. Never mind the oppressive farming communes all around and the tenement-style housing in the cities, even the upper echelons of the Soviet regime—granted safe passage from potential Cold War atrocities—were not afforded any special rights or privileges. It’s all the stranger that this bizarre mix of power and privation would have played out beneath a curative “rest home.”