Of all the retirees who take up a creative hobby, how many can say their seizures made them do it?

That seems to be the case with one 76-year-old woman, who had never shown much of an interest in poetry and suddenly became a prolific poet, writing as many as 15 poems a day, as reported in the neuroscience journal Neurocase (PDF).

The patient came to her doctor reporting memory troubles and episodes of spacing out for a few minutes at a time. After a number of tests, she was diagnosed with transient epileptic amnesia, a result of seizures in her left temporal lobe, which helps us process sensory information and store new information (though her doctors did not rule out dementia as a factor).

After a few medication attempts, the doctors landed on a very low dose of the anticonvulsant lamotrigine. It improved her memory and calmed her temporal lobe’s activity, as recorded by an EEG, a test involving electrodes placed against the patient’s scalp.

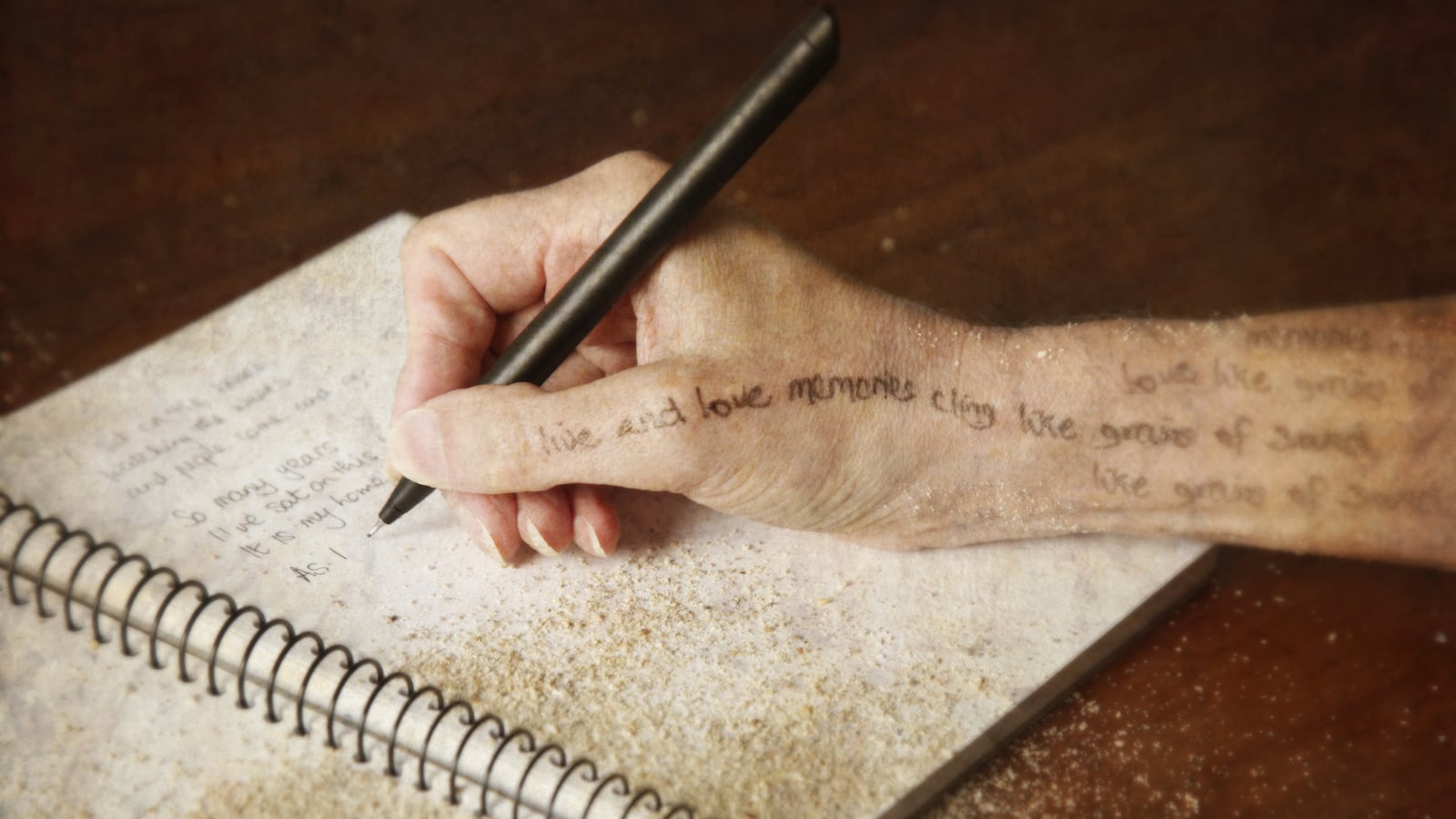

A few months later, the woman suddenly began to “versify,” writing 10 to 15 poems a day “on quotidian topics such as housework or about the act of versifying itself,” according to the paper. Compulsive writing, or hypergraphia, is a well-known, if uncommon, symptom of temporal lobe epilepsy. It affects about 10 percent of patients, though the writing is often disjointed and difficult to read. Our new poet wrote clearly, with both jokes and rhymes.

Here’s one of her poems:

My poems roams, / They has no homes / Yours’, also, tours, / And never moors. // Why tie them up to pier or quay? / Better far, share them with me. // Prose – now, that’s a different matter. / Rather more than just a natter. / Prose is earnest, prose is serious / Prose is lordly and imperious / Prose tells you, loud, clear, that / Life – life is dear.

The paper also reports that she became much more interested in wordplay, including taking great pleasure in finding word patterns in car license plates.

Her prolific output didn’t last long, though. By six months, her writing had become much less frequent, but she did maintain a fondness for wordplay and still produced the occasional verse.

So what happened? The woman’s doctors attribute the poetry, in large part, to a phenomenon called forced normalization, as a result of the anti-seizure drug. Generally put, forced normalization is the appearance of odd psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis, in a patient whose epilepsy has been controlled by medication. Seizures of the temporal lobe have an epicenter, called a focal point, which is what anticonvulsants are acting on to halt the episodes. But a drug like lamotrigine is not selective, and so it also affects the behavior of the rest of the temporal lobe.

“It’s the act of suppressing the temporal lobe that makes people act compulsively creative,” said Alice Flaherty, a Harvard neurologist who has written extensively about her own hypergraphia. “They’re not creative during their seizure. It’s after, when the temporal lobe is a little bit stunned.”

Disappointing though it might be to aspiring poets looking for a creative boost, lamotrigine alone isn’t enough to trigger hypergraphia. Instead, it’s probably the drug having just the right effect on a hypersensitive temporal lobe.

The connection between temporal lobe epilepsy and creativity is well known. Lewis Carroll, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Edgar Allan Poe, and Vincent van Gogh all likely experienced the condition. And the relationship between verse and unusual temporal lobe activity isn’t just noticeable in people with a diagnosed neurological disorder: A 1985 study of students who enjoyed writing poetry in their free time showed that they had many more spikes in temporal lobe activity, as recorded by an EEG, than their non-poet peers.

Because creativity and neurology are both on a spectrum, Flaherty is extremely wary of crossing the line into diagnosing personality traits as disorders. “There’s a nasty tendency to look at artists in terms of their weird quirks,” she said. “This woman is doing pretty well. She writes these funny poems. You don’t want to pathologize it too much.”

Neurologists aren’t the only doctors who can fall prey to putting a negative stigma on an unusual condition.

“Acromegaly [a hormonal disorder that results in extreme height] can cause all sorts of problems, but it’s really good if you play basketball,” Flaherty said. “For a lot of people with epilepsy, the seizure is the disorder. Their poetry, they like doing it, so it’s offensive to them to say it’s part of their disorder. The disorder is the part that causes you trouble.”

But even if the creativity itself isn’t pathological, isn’t a rapid personality change late in life something to be cautious of?

“There’s an idea of a unitary self you have to be faithful to, but I see my patients change their personality all the time. Why is that so wrong? Being changed by your college experience isn’t necessarily that much healthier than being changed by a drug,” Flaherty said.