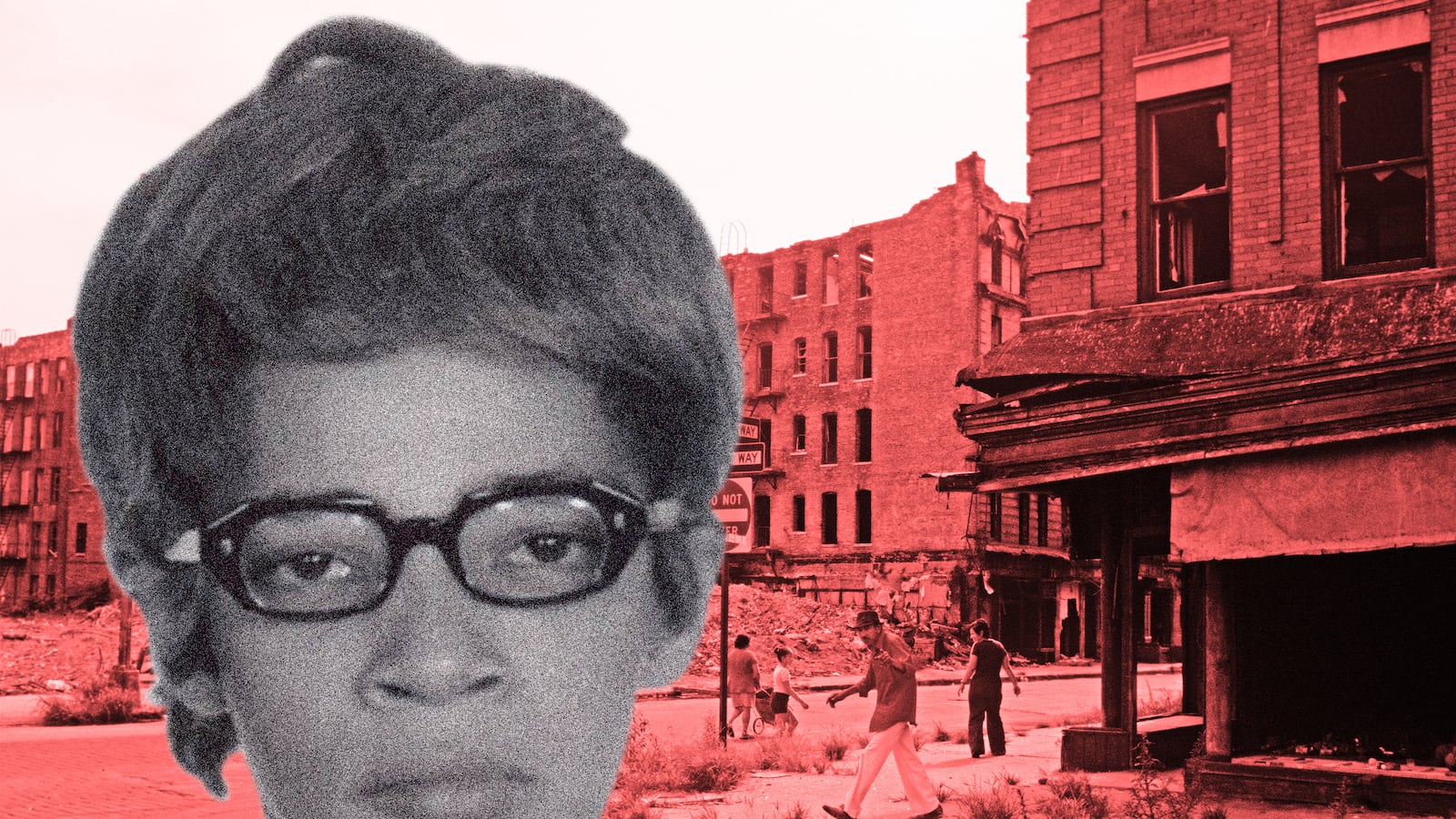

Serial killer Jesus Aguilera came to us from Cuba after the Castro regime emptied its jails and mental hospitals onto our shores more than three decades ago.

On Monday afternoon, the 61-year-old Aguilera stood impassive in a Bronx courtroom as the older daughter of one of his victims confronted him with a searingly beautiful vision of divine justice.

“As you take your final breath, I pray that your last vision is of the Almighty God surrounded by all the victims, known and unknown, and you vividly see these women, joyful, healthy, powerful, and whole, forever untouched by the evil that destroyed you and your humanity,” the daughter, Robin Bynoe, said as she addressed Aguilera directly in her victim’s impact statement prior to his sentencing for the 1981 murder of her mother.

Any remaining shred of humanity would have demanded some kind of a reaction from Aguilera. He continued to evidence none at all, having been blank-faced since being led into the courtroom. He had taken a sidelong glance when the daughter rose to deliver her statement to the sentencing judge but had gone back to gazing impassively ahead as she began to speak.

“I love and am very proud of my mother,” Bynoe said. “I say again, I love and am very proud of my mother.”

Bynoe reported that her mother, 35-year-old Tolila Moore, had just shaken off a longtime drug addiction, re-established a connection with her four children, enrolled at Fordham University, and gone to work at Catholic Charities helping others get clean.

“Tolila, with God’s help, began to ferociously snatch back her life,” Bynoe said.

Moore had then chanced to encounter Aguilera, who could have been sent by the devil himself. The prosecutor would say that “murder” was too gentle a word for what he did to her that day. Her daughter now recalled to the court that three nuns who had worked with her mother had come to the funeral.

“They praised my mother for her strength, courage, kindness, and strong work ethic,” the daughter remembered aloud.

As the daughter spoke, Aguilera worked his jaw, slowly, as if he were absently chewing gum he did not have. He gave no sign he even heard Bynoe as she addressed him directly.

“To the murderer, my God asks that I practice forgiveness and mercy,” Bynoe said. “You have been given mercy. You are still alive.”

Bynoe then invoked that vision of divine justice, which would have stirred even a determined atheist and nearly anyone else save the man to whom she directed a few final words.

“Lastly, my family and I urge, implore, and pray that the legal system will extend mercy and justice to all your victims and their families by keeping you caged for all the remaining days of your life,” the daughter concluded.

Justice Troy Webber asked Aguilera if he had anything to say. He replied through a Spanish interpreter, though he almost certainly speaks English after spending more than 33 years in an American prison for two other torture murders along with sexual assaults and the near-killings of a 15-year-old girl as well as an elderly woman who had admitted him into her home out of kindness to a newly arrived refugee.

“No,” Aguilera said.

Webber began by saying that she had long been opposed to capital punishment.

“But this is one of the few cases where I would have no problem sentencing you to death,” she then said.

The most she could impose was 15 years to life, to be served concurrently with his two other life terms.

“There should be absolutely no reason why this defendant is ever released from incarceration,” she ended by saying.

The court officers led the blank-faced Aguilera back to the holding cell. The daughter, Bynoe, had taken a moment during her statement to thank Det. Malcolm Reiman of Bronx Homicide as well as the prosecutors. She now turned to embrace the lanky, kind-eyed Reiman, whom the family had come view as the embodiment of all that is good and too seldom appreciated about the NYPD.

“You’re the best,” she said.

Reiman was quick to say the case would not have been broken were it not for the dedication of fellow cops. Among them was the already overburdened detective who originally caught the case. He and the crime scene investigator who processed the shack where Tolila Moore had been found partially clothed, her hands and feet bound, a scarf around her neck that had been tightened with a chisel the way a tourniquet is tightened with a stick, only in this instance not to stem bleeding and save a life but to cut off air and eventually deliver death.

The murder had received not a newspaper line of public attention, but Det. Freddie Duran of the Crime Scene Unit processed the scene as if the case were on the front page. He managed to lift a fingerprint off a jar.

At the same time, Det. John Starr of the 42nd Precinct squad gave the case his all, even going out solo on his own time.

But despite Starr’s efforts, the big break did not come until 2009, when advancing technology combined with the equally dedicated Det. Arthur Connelly. Connelly and others in the latent print unit periodically ran lifts from old cases through a computer database that had not existed when they were originally collected.

In June 2009, latent print called Lt. Sean O’Toole of Bronx Homicide and said they had matched the print from the Moore murder scene to a man named Jesus Aguilera. O’Toole assigned Reiman to investigate.

Reiman was glad to discover that in another example of how things should be done, the medical examiner had retained scrapings from under Moore’s fingernails. A resulting DNA profile was submitted to another database that had not existed at the time of the murder.

“Sure enough, a hit for our Mr. Aguilera,” Reiman later said.

Reiman conducted a background investigation and learned that Aguilera had come to America as part of the Mariel boatlift in 1981. A Cuban prison officer is said to have escorted Aguilera down to a boat that was headed for Key West, Florida. Aguilera was briefly held at a refugee detention center in Arkansas before being released to a brother.

Aguilera was believed to have strangled at least four people in the nine months between his arrival in New York and his arrest for murder. Reiman spoke to two others who had been lucky enough to escape before Aguilera succeeded in killing them, including the teen the exported monster had lured into an abandoned hospital with the promise of designer jeans, then raped and began to strangle when she managed to jump up and run.

Reiman went with fellow Bronx Homicide detectives James Conneely and Carlos Infante to Great Meadow Correctional Facility, where Aguilera was already serving two life terms. Reiman presented Aguilera with a photo of the shack where Moore’s body was found. Reiman would later compare the effect to having placed a fragmentation grenade on the table and pulling the pin.

“His muscles tensed, his face turned red, his eyes bulged,” Reiman would recall.

Reiman asked him a question.

“Ever been there?”

Aguilera responded emphatically in the negative. Reiman showed him a photo of Moore lying face down at the crime scene. Aguilera immediately denied knowing her.

“How do you know you don’t know her?” Reiman asked. “She’s face down.”

Aguilera remained adamant. Reiman suggested that maybe he just did not remember being at the shack or meeting her. Aguilera repeated his denials, which was fine with the detectives.

“Sometimes in a case like this, a denial is as good as an admission,” Reiman later said. “He’s got his fingerprint at the scene and his DNA on the victim.”

Aguilera was indicted for yet another murder. Reiman was at the arraignment holding a brown case folder marked “Tolila Moore F/B/35, Method: Ligature Strangulation Homicide.” The contents documented the efforts of all the dedicated souls who had worked so hard on a case that the press and city as a whole had met with a shrug.

Nobody had to tell the detectives that black lives matter, that all lives matter.

Aguilera initially pleaded not guilty but changed his mind after he learned that the details of his other crimes could be admitted at trial.

On Monday afternoon, two of Moore’s daughters along with her sister, two nieces, and a nephew arrived at the Bronx County Supreme Courthouse for the sentencing. They knew that Aguilera was still doing two life terms, but justice was still justice.

“It makes all the difference in the world,” the daughter, Bynoe, said.

That was all the more true in this instance because many people had assumed Moore had died as a result of slipping back into her old, negative ways.

“She didn’t get the grief she should have gotten,” her sister, Dorinda Cannon, said.

Cannon recalled that when she walked up to the open coffin at the wake she had seen something in Moore’s face.

“She looked like she was angry, like she wanted to say something,” Cannon said.

The detectives had now said it for her, proving that Moore had in fact fallen victim to a predator just when she was getting her life together.

“She was doing all the right things,” Cannon said. ”It makes us proud of her.”

Reiman was there along with prosecutors Rachel Singer and Adam Oustatcher. They went into Part 92 with the family.

“Indictment 865 of 2010, Jesus Aguilera,” a court officer announced.

A door to the right opened and Aguilera scuffled in with a cane, wearing a prison-issue tan top, green pants, and thick-soled black shoes. His head was shaved.

“We can proceed with sentencing,” the judge said.

Oustatcher spoke first, calling Aguilera “a man [who] preys upon the innocent and murders without warning just because he wants to.”

He said of the crime, “He didn’t just murder her, he tortured her.”

The prosecutor then said Moore’s older daughter wanted to address the court. Bynoe delivered a statement that surely would have made her mother as proud of her as the family was of her mother.

After Reiman got his hug, he stepped into the hallway.

“That makes all the difference,” he said. “What a wonderful family.”

He then headed back to work on his latest case because all lives matter.