Malls were, for many, structurally part of growing up—be it for after-school jobs, pierced ears, Cinnabon cravings, or awkward dates. For writer and critic Alexandra Lange, author of Meet Me By The Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall, it was where she skim-read the exploits of Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefield (her mother was firmly anti-Sweet Valley High) and bought her first miniskirt.

Despite being a pillar of the suburban experience, Lange notes the scornfulness with which it’s regarded: “‘Looks like a shopping mall’ is considered an architectural insult” and “‘mall rats’ are considered unproductive members of society.” Frank Lloyd Wright, when asked for a comment on a new mall, practically spat: “Who wants to sit in that desolate-looking spot?” In her introduction, Lange admits, “the mall was ubiquitous and underexamined and potentially a little bit embarrassing as the object of serious study.” Nonetheless, its reputation belies its cultural heft. “I started looking at shopping not as a distraction but as a shaper of cities,” she elaborated. “While architecture history tended to focus on suburban houses, and planning history looked to the highways, the shopping mall fell into the cracks.”

Yet its lifespan dates back as far as 1786, to glass-roofed, street-long arcades in Paris, and shaped the landscape literally and figuratively. Mall developers’ decisions reflect the redlining of the 1930s—racism entrenched into American geography—that trickled down in exclusionary ways for decades. Malls thread through pop culture: they’re the backdrop of movies from Valley Girl to Mean Girls, and in her heyday, Britney Spears promoted her debut. . . Baby One More Time with a 30-minute set performed in the middle of a mall. Meanwhile, Joan Didion’s 1975 essay “On the Mall” (anthologized in The White Album) details how “she goes in for a New York Times and comes out with two straw hats, four bottles of nail polish, and a toaster.”

The Daily Beast spoke with Lange by phone to further dissect how malls are a meaningful despite the all the ambivalence around them.

When did this fixation with the mall strike?

As a freelance writer, you’re always trying to keep up with new topics. But sometimes, you find that your stories kind of cluster around a topic that maybe you didn’t see was a big deal when you started out. That was essentially the scenario for this book. In 2018, I read some articles about the architect Renzo Piano designing this [California] mall called City Center Bishop Ranch, and there was a lot of Why would this Pritzker Prize winner be designing a mall. Like: This is crazy. I knew malls had an architectural history—I had read the biography of Victor Gruen [Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream] by Jeffrey Hardwick, which people know about because Malcolm Gladwell wrote about it in the New Yorker [in 2004]. I've read a lot of other books about mid-century suburbs, and my dissertation was about post-war corporate headquarters. I thought: It doesn't really make sense to be dissing the mall by saying an important architect shouldn't design it. I wrote an article for Curbed looking more critically at the dialogue around why people were saying that the mall was dead.

And then Hudson Yards opened in New York City, which, you know, is another mall… but people weren't calling it a mall. They were calling it, like, a “retail vertical” or something like that. Just using different words for something that was very clearly to me—a child of the ’80s—a mall. So again, I was like, What are you talking about? This is a mall. And then I started looking around the city. I picked out some previous examples, including the Winter Garden at the World Financial Center, and visited the construction site of this outlet mall that they're building on Staten Island next to the ferry terminal. People keep saying “Malls are dead,” but they're alive—a lot of money is going into things that, to me, look like a mall, but using new words. What pushed me over the edge was “shared streets.” I was like, Isn't this just like the pedestrian malls that were everywhere in the ’70s and early ’80s. So it’s about language, and how we understand public space, and how people are always trying to reinvent it for marketing purposes.

Also, malls are like 30-40 years old, which is about when architecture starts counting something as historic. So I felt that it was time to re-explore the original ideology.

About language: You say, in the book, that “avoiding the word mall offers more flexibility.” Changing the nomenclature can shift what we conjure for certain concepts—is this misdirection, or do these names reflect norms somehow changing?

The changing of the language seems to be very much led by real estate interests. It’s a little bit reactionary to keep calling them malls when the people who are making them are not, but I feel like that is the language that allows the most people to understand the spaces that I’m talking about. And I’m just gonna keep using it.

Hudson Yards, left, and City Center Bishop Ranch.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/GettyYou make it clear that the mall, aside from a capitalist space, is a collective space that gives people access to certain amenities they wouldn’t have otherwise. Yet the amenities of the mall seem like they shouldn't be the purview of the mall—they’re things that should be social responsibilities not entwined with privately controlled spaces. Did this prompt debates about what should be a social good?

Obviously, the mall is a capitalist structure. I’m not denying that it is a capitalist thing, but I also think it’s taken on other powers that are outside the capitalist structure.

The bottom line is, I agree with you. I think that air-conditioned communal spaces and clean bathrooms and ramps and elevators should be provided for the public—by the public. But that is not the world that we live in. And so I feel like I needed to describe the problems with having these things be a private provision, while also acknowledging that for many people, the mall is the best place to get these things. I don’t think it’s right to practice architecture and design criticism from a place that doesn’t acknowledge the real-world experience. I am very interested in how people are actually using things. In the context of my larger work, I support generalized public provision of all these things. But, for many people, the mall is the place to get those things, and has been for a long time. I feel it’s worth talking about, even if it’s not the ideal version of those amenities.

Did your research confirm what you already understood about malls from writing articles? How much was a surprise or unexpected finding?

On the architecture end of things, it confirmed what I already knew. I already had a strong background in postwar American modern architecture. I knew about [architect and mall designer] John Jerde—not the level of detail, but I knew that I wanted to talk about him because the Mall of America is obviously a very important centerpiece for any book about malls. But I did find a lot of interesting twists. One of my favorite discoveries was finding out that Ray Bradbury and John Jerde were friends, and that Ray Bradbury had actually written this essay “The Girls Walk This Way; The Boys Walk That Way,” about how Los Angeles needed more gathering places. I think finding out the kind of intellectual history of the mall was really fascinating.

I loved those references threaded in—Joan Didion too! And you drew from a passage from Émile Zola’s 1883 book Au Bonheur des Dames.

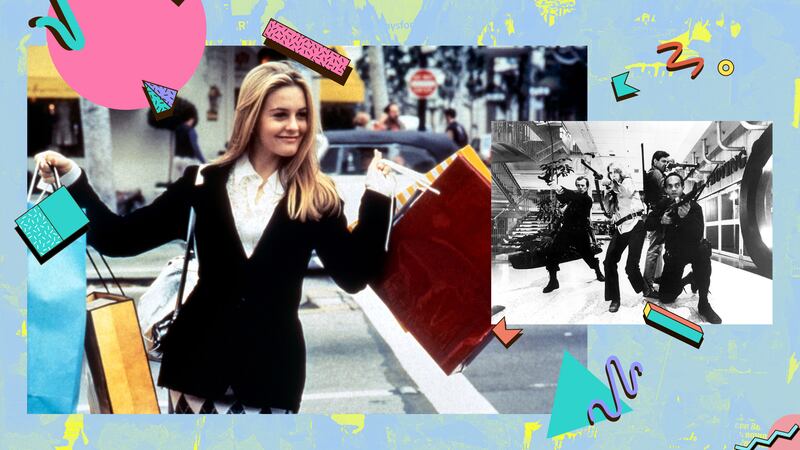

I have an architecture and design background, but some of the most fun parts for me were later chapters where I operate more as a cultural critic. Because none of us are one-track-mind people—I read a lot and watch a lot of things. Clueless is one of my all-time favorite movies. So to be able to incorporate all that into the book is very natural. I had never watched Dawn of the Dead before—a lot of people brought it up. I had to kind of watch it through my fingers, because I really hate horror movies, and that is a very gross low-tech horror movie.

Malls have been featured in movies like "Clueless" and "Dawn of the Dead"

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily BeastAnother thing that was really surprising to me was the long legal history of the mall as a public/private battleground. When I realized that Thurgood Marshall had written that first majority opinion in the Logan Valley case in 1968, I was like, Wow, I do not think that people are going to expect Thurgood Marshall to be in my book.

I was thrown!

So many smart and interesting people from so many different walks of life had also been interested in the mall. And since the general public has been to malls, and is still going to malls, I thought they should know it.

There's this biting line: “Good architects design museums; bad architects design malls.” On the flip side: “Museum keepers have always to a certain extent acted as commercial showmen.” How do certain aspects of the mall bleed into other types of sites—museum spaces among them?

There's definitely this specific time period where the discourse about the mall switches, in the early to mid-’70s, from accepting that good architects are going to be designing malls to looking suspiciously at elements of new museums that may recall the mall. The best example of this is I. M. Pei, who designed the National Gallery of Art’s East Building and also designed Roosevelt Field on Long Island. And in a bunch of the reviews of the East Building, people talk about the escalators wrapping the atrium and the food court that’s downstairs as being like a mall. And that has a negative inference.

This also goes for Cesar Pelli, the architect who designed this now-demolished addition to the MoMA with escalators under a glass ceiling. I wanted to talk about how commercial architecture has been written out of architectural history—yet what we need from those spaces, as humans, is often parallel. When we’re in a museum, we need to orient ourselves, we need to get from the first floor to the second floor smoothly; it’s nice if you have a view of a garden while you’re doing that, it’s nice to people-watch while you're doing that. What you’re doing at a museum isn't so distinctly different than what you're doing at a mall, in terms of how you’re moving your body. So to criticize an architect for being good at that seems completely wrongheaded to me.

And on top of that, in the ’30s through ’50s, museums and department stores were much more aligned in their promotion of modern design. In fact, the Good Design shows at MoMA came with catalogs that told you where to buy things and how much they cost. So this idea that there’s always been this kind of hard line between your museum up on a pedestal and your mall down here in the trenches selling people shit, is absurd. And not historically accurate.

The aesthetic goes for a lot of Silicon Valley headquarters as well. What's happening now is that a bunch of Silicon Valley companies are actually looking to old malls to repurpose them as offices—Google X is in a former mall, and Epic Games is working on adapting a mall in North Carolina into their new headquarters.

Right, there’s this retrofitting of existing languishing spaces for new purposes. Is it mostly corporate intervention, or is there potential for more variety?

There is a lot of creative thinking going into repurposing malls. This community college in Austin took over an old mall and is using it for classrooms and their computer center. They don’t need all the space they have, so the public TV station in Austin has taken over part of it and put in its offices. A lot of different professions need open column-free space and are looking at things like former department stores. They’re going for way less money than they would have 10 years ago because the owners know that they’re not going to be used for retail again.

You cite Barbara Kruger's work (“I shop therefore I am”) and this gendered association of the mall: “Postwar American culture pushed women into the role of shopper in chief, even as it judged them for overconsumption.” Do you feel like things have evolved any, or is this sexism doomed to endure?

My last book was called The Design of Childhood, and a lot of spaces for children are really spaces for children and their mothers, traditionally. So I was very aware of a dynamic around men designing spaces for women, which is—by and large—what happened at the mall. I was hoping I would find more architects or developers who worked on malls who are women, but I didn’t really find that in the history, because the real estate profession remains dominated by men.

I still feel like shopping is constructed as a feminine activity. There are more men talking about fashion—yet, in a lot of cases, shopping spaces are seen as feminized spaces. That can be an exploitative relationship: the mall can be read as a machine designed to extract money from women. But I do think that women find a certain amount of freedom in going to the mall, spending their own money, figuring out how they want to present themselves.

The aesthetics of the mall used to hinge on this idea of travel and fantasy, integrating a mash-up of European design flourishes. But shopping online now seems the place to explore and fantasize. Do you think that some aesthetic aspect of the mall—of not really being anywhere—has also lessened its appeal?

You’re right that the mall was a fantasy environment. And that comes through from its origins—you went to the mall and were in this other space that was probably slightly more cosmopolitan than your town. The extreme version of that is the Mall of America, where it’s like this wing is New Orleans and this wing is Paris and you’re still all under one roof. But today, people are more cosmopolitan. You don’t have to go to Minneapolis to simulate Paris—you could go to Paris. Where we are as a country in terms of travel and exposure to other cultures and visuals of other places is much different than it was in the early ’80s and ’90s, when the Mall of America opened.

Vintage scenes from The Mall of America

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/GettyPart of the problem with a lot of malls today is that they become pretty generic in their aesthetic. If you remember when Drake's house was on the cover of Architectural Digest, the interiors and surfaces were lined in marble. A friend of mine was like This looks like a mall in Dubai. Malls now are just coated in marble, and have big, sparkly chandeliers. It's a slightly dumb and generic version of luxury. It doesn’t feel like you're anywhere, and it also doesn’t feel special. I don't think they’re necessarily doing the best job at making themselves attractive to the next generation. I do think that some of the older models that I wrote about were interesting, offering a glimpse at something that you couldn’t get somewhere else. I would like it much better if they would lean back into some expression of the place that they're in.

The mall was once considered the ideal adolescent playground; do you think teenagers find release through other means today?

I think teenagers still crave the social aspects of the mall. I don’t think that they necessarily have to buy clothes at the mall anymore. But just thinking about the behavior of my own teen and tween, what do they do after school? They go and buy candy, they go and buy bubble tea, they go and sit in a park. We live in the city, so you can do those things on the streets. But if we lived in the suburbs, where would the candy store be? It would be at the mall. So I think they just need to go to a place and spend $5 and sit with their friends. It’s like “cheap date” activities to get together in person. Teens are always online, but sometimes they’re online while they’re in a physical space with their friends. So the two are not at all mutually exclusive.

You break down how systemically inbuilt the racism and classism was to American mall locations, being expressly inopportune for certain communities. Today, you mention a new approach of using malls as ethnocentric marketplaces welcoming communities who wouldn’t have been included in these spaces in the past. Is that a positive evolution? Or just circumstantial turnover?

I think it’s progress. But it’s a different era. Some of these uses, particularly the ethnocentric marketplaces, which have tended to be largely Latino and Asian, really reflect the changing demographics of the suburbs. So if you continue to try to run your mall the same old way, with national chains in those suburbs, you would fail. It’s partially an acknowledgement of the commercial reality. That leads to more ownership by people of color, which then makes the malls potentially welcoming to groups that have been seen over time as threatening, particularly Black and brown kids.

In the LA Times review of my book, the writer Carolina Miranda brought up this great example, the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza in Los Angeles. It’s in a historically Black neighborhood, which community groups have been trying to buy because they don’t want another one of these big private equity companies to take it over. They want it to serve their community. So in order to make malls welcoming, they need ownership groups that reflect the demographics using the mall. It’s clear that there needs to be a greater diversity of mall ownership, of who’s in charge.

Do you think part of the draw to e-commerce is there’s a more proactive aspect that the consumer has of deciding to support a business? That people feel like they want to partake in or reinforce certain community aspects sidelined elsewhere, including the mall?

I feel like it’s still only like a relatively small percentage of people that can make those ethical consumerism decisions about most of their shopping, because that shopping tends to cost more, and they have to do more research to find it out. In real terms, how much of that kind of shopping is siphoning people away from chain stores and other things that you find at the mall? I can definitely see how that would appeal to, you know, urban twentysomethings that feel well versed in that. But I just don’t know.

A Britney Spears concert in a mall in Canada.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/YouTubeTowards the conclusion of the book, you posit that: “Shopping isn’t going anywhere, and it’s so much nicer to do it together.” Do you still see the mall as a rallying force?

I think the future of malls is less about shopping for clothes, and more about food and experiences. If you look at what’s replacing department stores, a lot of malls are leaning into these food court halls and gourmet food options. It’s the social aspects of the mall coming to the fore, and the “errand” aspect falling away. All of your boring shopping is really much easier to do online. The mall becomes more desirable for social shopping, like for buying a prom dress with a friend, or to meet someone for lunch and then do a few things. Why you would go to the mall is, actually, changing the architecture of the mall.